A comparison of satellite images from NASA showing the effects of the 22-year megadrought on Lake Mead. Photos Lauren Dauphin/NASA Earth Observatory.

On October 13, 1893, Major John Wesley Powell, celebrated explorer, geologist and Civil War veteran, addressed delegates of the Second Irrigation Congress in Los Angeles, declaring to the capitalists, politicians and boosters attending (and whose main agenda was to develop the arid West), “What matters it whether I am popular or unpopular? I tell you, gentlemen, you are piling up a heritage of conflict and litigation over water rights, for there is not sufficient water to supply these lands.”[1] Powell’s blunt prophetic statement did not win support. The delegates booed him off the stage.

Twenty-four years earlier, Powell led the first attempted and successful geological expedition of the Colorado River, through the Grand Canyon by boat. The ten men, including Powell’s brother Walter, began their river exploration at Green River, Wyoming, on May 24, 1869, just two weeks after the first transcontinental railroad pushed westward with its first paying passengers. In wooden dories, with ten months of rations and supplies, the group traveled southwest on the Green River to the confluence with the Grand (later renamed Colorado), near present-day Moab, Utah, and then through the uncharted Grand Canyon. All but three of the men completed their monumental adventure on August 30, 1869, landing near where the Virgin River now empties into Lake Mead. Just two days earlier, the disgruntled threesome had deserted the party and scaled the canyon’s dangerously steep walls, only to mysteriously disappear on the plateau above. Under Powell’s determined leadership, the expedition had traversed some 930 miles of waterway, mainly within the Colorado Plateau’s sublime canyon country. Powell went on to organize a second expedition in 1871, during which he gained a deeper understanding of the region’s topography, geology, and Indigenous inhabitants.[2] The painter Thomas Moran traveled with the group, immortalizing the imposing landscape in some of his most recognized paintings of the American West.

Powell’s official government report titled The Exploration of the Colorado River of the West and Its Tributaries was published in 1875. However, a more prescient account appeared three years later as the Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, in which Powell described to Congress the region’s unique physical characteristics, along with visionary observations calling for a new adaptive land distribution system of small, cooperative farming settlements with land tethered to water rights and within irrigation districts based on watersheds. Powell forewarned that the customary but arbitrary Jeffersonian grid concentrated water resources randomly and unfairly; an equitable land distribution framework could only work in the American West if sufficient surface or groundwater were uniformly and proportionately available to all landholders. He argued presciently that west of the one-hundredth meridian, where annual rainfall was less than twenty inches, only a few areas could support such large-scale agriculture or development.[3]

Powell’s vision was informed by Mormon irrigation practices, which, in turn, borrowed from the network of community-maintained water ditches or acequias of the Hispanic southwest. Author Donald Worster points out how this democratic “communitarian ethos” shaped the Mormons’ shared distribution of irrigation water.[4] Having already gained valued insight into “making the desert bloom” after nearly two moderately successful decades farming in harsh Deseret, the Mormons impressed upon Powell the correct way to make some land of the arid West productive. Powell’s sound advice to settle and develop only a small portion of farmland under production today was obviously ignored, leading to the dire predicament that now confronts the American Southwest.

A view of Hoover Dam in July 2022. In 2000, Lake Mead’s water line was at the bottom of the penstock’s walkway and the foreground was submerged. Photo: Kim Stringfellow.

Today, over-apportioned waters of the Colorado River and its tributaries serve forty million people in seven Western states and Mexico while supporting 1.4 trillion dollars of economic activity within the Colorado River Basin every year.[5] Seventy percent of its water irrigates 5.5 million acres throughout the 246,000-square-mile basin.[6] The Colorado, a modestly sized silty river with its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains, is only one-thirtieth the flow of the Mississippi, but it can fluctuate widely in terms of annual flow. Every drop of water is spoken for, making it the one of the most engineered, controlled and overused waterways on the continent. Consequently, the Colorado no longer reaches its delta at the Gulf of California, some 1,450 miles from its source, except on rare, intentional occasions.[7]

Ours is a hydraulic civilization that Cadillac Desert author Marc Reisner forewarned would collapse if the Colorado’s water supply was suddenly shut off. Reisner speculated on how most of Southern California, Arizona, southern Nevada and much of the interior West would require evacuation within four years when reservoir carryover capacity had diminished entirely. Reisner published his seminal book in 1986, just three years after Lake Mead experienced a record high level measured by shoreline elevation of 1,225 feet) in the summer of 1983. As of mid-August 2022, Lake Mead’s shoreline had dropped to 1,042 feet, or 27 percent capacity—the lowest since the lake was filled in 1937.[8] If Lake Mead falls below 1,025 feet, only one year of stored water is available for Lower Basin states (Arizona, California and Nevada).[9] At 895 feet, the lake is at “dead pool” where water can longer pass through the dam downstream, let alone produce hydropower. Lake Powell, impounded by the controversial Glen Canyon Dam completed in 1963, is in a similar predicament. The lake is at 25 percent capacity and 166 feet below full pool level at 3,534 feet elevation. If the dam drops to 3,490 feet, it will no longer be able to generate electricity, severing power to as many as 5.8 million customers. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s projections list a glaring 27 percent chance in 2024 that Lake Powell will have slipped below minimum power pool levels.[10]

This alarming situation is the result of years of excessive overdrafts, along with extreme drought occurring over the past twenty-two years, which have created megadrought conditions that are further complicated by intensifying climate change. But poor long-term planning and over-allocation of the river’s resources combined with unsustainable development in arid locations largely unsuitable for supporting surging population growth have created a “supply-demand imbalance.” Add the historic rejection of scientific data while the region’s irrigation infrastructure was being planned, and it becomes clear how we arrived at this critical moment. Sadly, many climate scientists believe the scale has tipped. Large swaths of the American Southwest are heading toward aridification that will be permanent and catastrophic—unlike the cyclical droughts of the past.

Today, it’s widely understood that the Colorado River’s water was from the beginning over-allocated. But how could such a gross miscalculation occur? The Colorado River Compact of 1922 geographically divided the Colorado River Basin at Lees Ferry in northern Arizona into two water-management regions: The Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) and the Lower Basin (Arizona, California and Nevada) and holds the key to this puzzle.[11] The compact determined that each basin would be promised 7.5 million acre-feet [12] of Colorado River water for beneficial consumptive use in perpetuity, thereby reserving water for future development in the Upper Basin while allowing the Lower Basin states to continue with existing development.[13]

The compact was based on a projected annual flow estimate of 16.4 million acre-feet at Lees Ferry, whereas the actual long-term average flow is now significantly less—from 2000 to 2020, it averaged 12.6 million acre-feet[14] and varies widely year to year.[15] The compact planners additionally assumed that there would be an annual surplus flow between four to six-million acre-feet that could be utilized. So when the compact was ratified, it was under the illusion that the river provided twenty to twenty-two million acre-feet of water every year. It wasn’t that the compact’s planners weren’t aware that their overly optimistic flow models were wrong—they simply chose to willfully ignore available “inconvenient science” so that reckless overdevelopment of the Colorado Basin could proceed, leaving future water managers to deal with the outcome.[16] Indeed, today’s water managers are now forced to reckon with the compact planners’ greed and carelessness precisely 100 years after the document was created.

A sign at Hemenway Harbor at Lake Mead’s National Recreation Area near Boulder City, Nevada, marks how far the reservoir has dropped in elevation since the lake was last considered full in 2000. Photo: Kim Stringfellow.

The Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 ratified the 1922 compact, authorizing $165 million in appropriations to construct Boulder Dam (renamed Hoover Dam in 1947) at Black Canyon, on the Arizona-Nevada state line. Boulder Dam and other downstream irrigation projects, including Imperial Dam and the All-American Canal, were built to placate California’s Imperial Valley farmers threatened with disastrous seasonal flooding every spring. One of these deluges created the Salton Sea in 1905, wiping out most of the valley’s farms and settlements that year. The Boulder Dam would generate 2,080 megawatts of electricity for Los Angeles and other Western states, but, more importantly, it would impound water in the country’s largest reservoir, with storage capacity for two years of average Colorado River flow, in the newly created Lake Mead. This endeavor was the crown jewel of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, providing much-needed relief and jobs for laborers hit hard during the Great Depression, through the Public Works Administration.

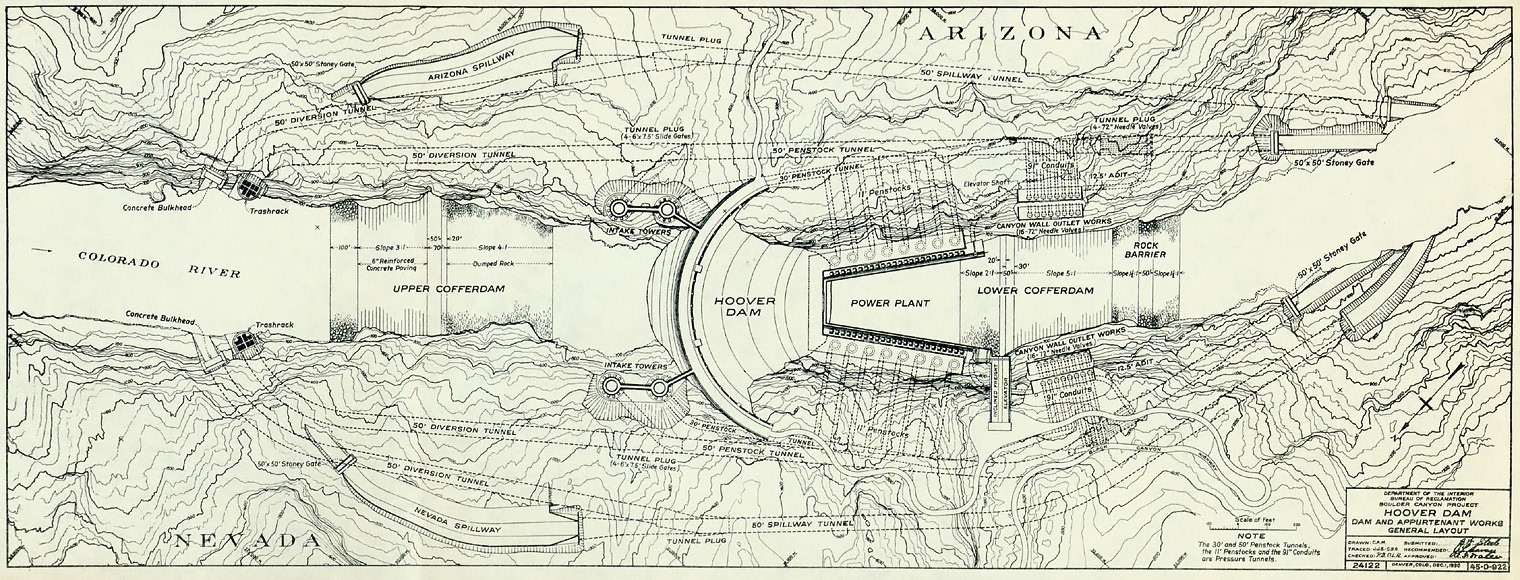

Hoover Dam is a 726-foot-tall arch-gravity concrete dam, 1,244 feet in length, with a 660 foot-wide base that elegantly curves at its crest to forty-five feet in width. Travelers could drive across the dam until 2010, when the U.S. Route 93 bypass was completed. This extraordinary dam weighs 6.6 million tons and for many years was the tallest structure worldwide. John L. Savage, as the Bureau of Reclamation’s chief civil engineer, oversaw the structural design of the dam. Los Angeles-based architect Gordon B. Kaufmann, who was the Bureau of Reclamation’s lead architect, was responsible for Hoover’s stunning Art Deco exteriors and details.

Although site preparation had begun in 1929, actual dam construction did not commence until 1931, when workers undertook the diversion of the Colorado River. To accomplish this tremendous feat, laborers blasted four massive tunnels, fifty-six feet in diameter, out of the canyon’s igneous rock walls. After the excavation’s completion, the rubble was dumped to block the river’s ancient channel until the Colorado’s waters rushed forth into the bypass created on the Arizona side of the canyon. Two cofferdams (enclosures within a water body that allow dry access for construction when water is pumped out) were built to excavate the forty feet of river bottom required to create a stable foundation in bedrock.[17] Specialized crews began to scale the canyon, manually drilling and blasting the walls. The 400 men who performed this task were known as “high-scalers.” The job required skill, strength, agility and, above all, guts. Film footage made during the dam’s construction shows these fearless men jumping and swinging perilously back and forth across the canyon above the river floor with dynamite and jackhammers in hand. Like seasoned circus acrobats, the men effortlessly descended on ropes after each blast stripping away underlying loose rock from the abutments, readying them for the massive 4.5 million cubic-yard concrete barriers that would take form. Notably, the prep work was completed by spring 1933.

U.S. Department of Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Boulder Canyon Project, map, 1930. Wikipedia.

Raising the dam presented many challenges, from sourcing, mixing and pouring concrete required to build such a massive structure to developing a new, advanced method to cool the concrete as it set. Without doing so, the dam would have taken 125 years to reach an ambient temperature to be usable, while the heat generated would create cracks and stresses, compromising the dam’s overall integrity. The solution was to pour a series of 215 trapezoidal columns that contained a steel cooling pipe network within each one of them. Previously untested engineering solutions such as this innovative cooling system allowed the dam’s completion by May 29, 1935, two years ahead of schedule. Over the following year, the two diversion tunnels were converted to spillways capable of moving 400,000 cubic feet of water per second. Two power plants, four penstocks, two intake towers, and other features later became operational, and by the fall of 1936, the dam’s generators were producing power.[18]

Construction of the dam employed 21,000 men, averaging between 3,500 and 5,200 working daily. Such a massive influx of workers and their families to the region required the development of government-funded housing and services, scheduled initially before dam construction began. Although the closest settlement was Las Vegas, Nevada, with a population at just over 5,000, the federal government decided against siting operations there and instead built the government camp near the dam site. A nearby “Ragtown” encampment had also quickly sprung up in the river’s flats as desperate Depression-era job seekers began converging on the site once the dam had been authorized, waiting to be hired. Ergo, as a result, Las Vegas’s population quickly ballooned to 20,000. By 1931, Nevada had repealed its gambling ban, opening the floodgates for the proliferation of speakeasies and casinos—popular draws for the dam workers but not for construction management.

Boulder City, designed to house 5,000 families, opened in late 1931 and was operated with clean living in mind. Access was tightly controlled—no gambling or alcohol was allowed, and one needed a permit to enter the settlement; also, it was racially exclusive. Six Companies, Inc., the joint venture awarded the government contract to construct the dam,[19] attempted to keep its workforce mainly white; its government contract stipulated that Six Companies would not hire “Mongolian” (Chinese) laborers. But by 1933, Six Companies was compelled to hire African Americans, who would undertake some of the most challenging work in the hottest parts of the site. In all, no more than thirty Blacks worked at any time during the dam’s construction, nor were they or their families allowed to live in Boulder City. Some Hispanics and Native Americans were hired, but like African Americans, they were forced to live elsewhere. A rare photograph from the National Archives shows a crew of Indian men, one Yaqui, one Crow, one Navajo, and six Apaches, hired as high-scalers. All workers suffered from the excessive desert temperatures, and many fell prey to heatstroke, exhaustion, or death. The extreme working conditions drove laborers to attempt unionization, but the efforts failed. Six Companies’ management knew that desperate Depression-era workers had little choice but to abide under its rules.

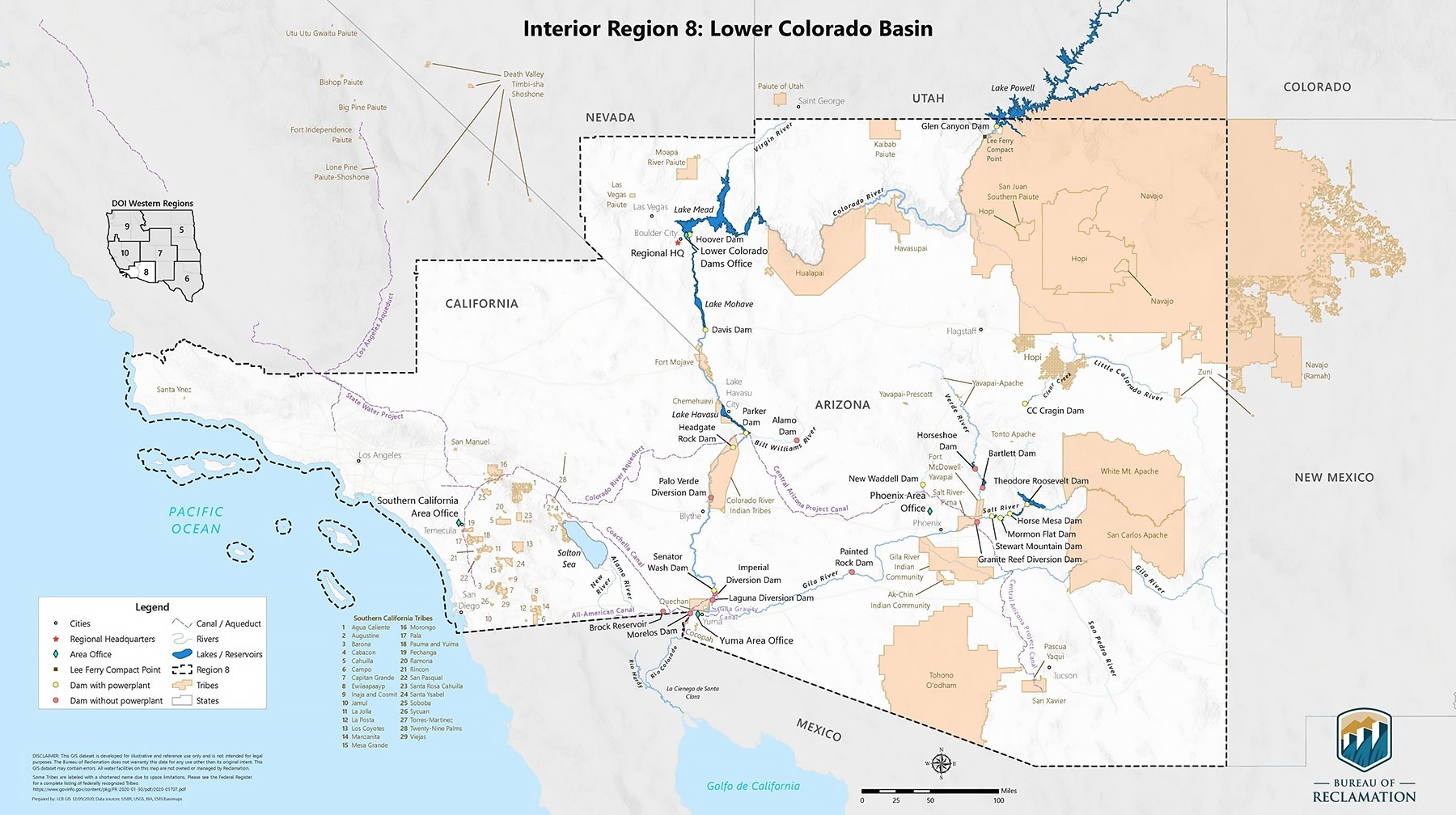

Map of the Lower Colorado River Basin. Courtesy of Noe Santos, Bureau of Reclamation.

While Boulder Dam was being built, construction of Parker Dam had begun 150 miles south in 1934 to allow diversion of the Colorado River into the under-construction Metropolitan Water District of Southern California’s 242-mile-long Colorado River Aqueduct that would eventually bring water to fast-growing Los Angeles and vicinity.

One hitch: Arizona’s Governor Benjamin B. Moeur and his state attorney general declared the project illegal, proclaiming martial law on November 10, 1934. One hundred Arizona state militia were sent from Phoenix to the river at Parker, Arizona. Sympathetic Arizona state legislator Nellie T. Bush, who owned and operated two ferryboats with her husband, Joe, piloted the men as “Admiral of Arizona’s Navy” in protest. The militia attempted to halt construction but got stuck in the river, and ironically California’s “enemy forces” came to their rescue. The act stopped Parker Dam construction temporarily—the dam and aqueduct were completed in 1938. Still, the skirmish emboldened Arizona to continue its fight for what it considered a fair guaranteed allotment of Colorado River water.

The newsworthy confrontation allowed Arizona politicians to later lobby successfully for the federally funded Pima-Maricopa Irrigation Project. However, Arizona wouldn’t agree to ratify the Colorado River Compact until 1944, in return for federal support for the Central Arizona Project (CAP), which began conveying Colorado River water to Phoenix, Tucson and central Arizona agricultural users in 1993 at the Mark Wilmer pumping intake just northeast of Parker Dam. CAP would be the longest and most costly aqueduct ever built in the U.S. and would tip the water scale at the turn of the millennium when Arizona began using its full 1922 compact allotment of 2.8 million acre-feet of water.[20] Today, CAP supplies water for 80 percent of the state’s population, along with irrigated farmland. However, Arizona made one key concession when Congress authorized CAP in 1968—in the event of a severe shortage on Lake Mead, California’s water deliveries would take priority. CAP’s end users would lose 22.8 percent or 720,000 acre-feet of their annual entitlement.[21]

As mentioned earlier, Lower Colorado River Basin apportionments are based on the 1922 compact that allows up to 7.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water per year for consumptive use. California’s entitlement is 4.4 million acre-feet, Arizona’s is 2.8 million acre-feet,[22] and Nevada receives up to 300,000 acre-feet annually. Mexico’s portion, ratified by the 1944 treaty agreement, is 1.5 million acre-feet. Before CAP became fully operational, California had for years consumed 20 percent over its apportionment, on average 5.2 million acre-feet per year. Notably, California does not contribute any water to the Colorado River system but is a major agricultural producer.

During the 1990s, Bruce Babbitt, as Secretary of the Department of the Interior, forced California to wean itself off the surplus water with his “4.4. Plan,” designed to help the state reduce its yearly water use by 800,000 acre-feet. This led to the controversial Quantification Settlement Agreement of 2003, between the Imperial Irrigation District (IID), the San Diego County Water Authority and other federal and state water agencies, which transferred surplus irrigation water to San Diego.[23] Additionally, the agreement implemented water conservation measures such as the concrete lining of the All-American Canal that is directly tied to lowering water levels at the ecologically-challenged Salton Sea.[24] Notably, IID’s senior water right allows it, on average, to use three-quarters of California’s apportionment of the Colorado River or about 3.1 million acre-feet annually.[25] The IID is one of the most powerful stakeholders on the Colorado River, holding water rights for one-fifth of the basin’s flows. However, Native American Tribes in the Upper and Lower Basins have more significant water rights than IID—but many of these claims have not been fully developed or used.

In 1908, the landmark Winters vs. United States case held that Tribes “have a reserved right to water sufficient to fulfill the purpose of their reservations, and this right took effect on the date the reservations were established.” The Supreme Court ruling determined that tribal water rights are generally senior to those of non-Indian users, including the states, and that their rights cannot be forfeited through non-use as established by water rights laws governed by the principle of “prior appropriation.”[26] Still, it took a 1963 Supreme Court ruling in the long-running Arizona v. California series of cases to recognize and quantify reserved water rights of five Lower Basin Indian Tribes, including those of the Chemehuevi, Fort Mojave and Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT), whose membership of 4,500 includes four distinct tribes.[27] Still, quantification of tribal water rights remains undetermined, and many outstanding, unresolved claims exist. Consequently, Tribes of the Upper and Lower Basins continue to pursue both litigation and negotiated settlements to establish their legal allotments.

Twenty-two of thirty federally recognized Tribes control 3.2 million acre-feet of Colorado flows on both the Lower and Upper Basin, or 22 to 26 percent of the Basin’s average annual water supply.[28] The unresolved water rights for twelve Tribes will increase overall tribal apportionments, counted against those made to the states.[29] Notably, most Tribes cannot fully utilize their water rights due to a lack of funding to develop or update conveyance infrastructure or create water storage, nor are they compensated for not drawing on their entitlement, which actually has helped to keep reservoir levels up during past drought years. The most significant first-priority water right in Arizona belongs to CRIT. Its Tribal council recently supported the Colorado River Indian Tribes Water Resiliency Act of 2021 (S.3308), allowing CRIT to lease a portion of its water to basin users outside reservation boundaries while protecting riparian habitat. Doing so had not been previously allowed. If enacted by Congress, S.3308 will authorize the transfer of 50,000 acre-feet of CRIT water per year for three years to Arizona municipalities and other state users.

Notwithstanding unused tribal allotments, the Colorado River has operated for years under a “structural deficit,” meaning that less water enters the system than goes out. This deficit exists with basin states using less than their full 1922 compact allotments. For example, in 2021, Lower Basin states’ consumptive use totaled nearly 7.1 million acre-feet (approximately 4.4 million acre-feet for California, 2.4 million acre-feet for Arizona, and 242,168 acre-feet for southern Nevada).[30] Mexico received just over 1.5 million acre-feet treaty apportionment that same year. Consider that total evaporative losses in Lower Basin reservoirs are equal to about one million acre-feet per year, on average the Lower Basin, including Mexico, is “using” nearly ten million acre-feet annually.[31] Evapotranspiration, which includes evaporation from open bodies of water and water transpired from riparian plants, is an important consideration because this reduction does not officially count against the state’s yearly allotments.[32]

The combined consumptive use of the Upper Basin states (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming), including evaporative losses, was roughly 3.5 million acre-feet in 2021. This represents one-million-acre feet less water than the Upper Basin consumed in 2020—far less than the 7.5 million acre-feet apportioned to each basin in the original 1922 compact. The Law of the River, a collection of legal documents including the various compacts mentioned above, as well as federal laws, contracts, court decisions and decrees, contracts and regulatory guidelines provides a framework to manage and operate the river.

The 1948 Colorado River Compact determined Upper Basin annual apportionments and made them dependent on the ability to first deliver 7.5 million acre-feet of water annually to the Lower Basin states, Mexico, Native American Tribes and other users before apportioning any water to the Upper Basin. Even so, each Upper Basin state receives only a percentage of what remains; Colorado receives up to 51.75 percent, Utah 23 percent, Wyoming 14 percent and New Mexico 11.25 percent. Given the river’s current average flow level at 12.6 million acre-feet, this leaves the Upper Basin states in a continuous deficit that will persist into the future.[33] The Utah River Council stated in a 2022 draft document, “If Colorado River flows decline to a total of 30 percent below the twentieth-century average flow, or to 10.6 million acre-feet per year, and water use does not decrease, all Upper Basin states would overuse their water allocation by more than two million acre-feet.”[34] The Utah River Council suggests that the Upper Basin is currently overusing 500,000 acre-feet each year—even without further declines from megadrought and climate change.[35]

Basic Management Inc. Lake Mead intake pipes are shown in the center distance. To the right is the original 1971 valve that supplied Las Vegas with drinking water until April 2022, when lake levels dropped so drastically that it was exposed above the water line. Photo: Kim Stringfellow.

With this in mind, it seems unfathomable that some southwest Utah politicians and regional planners continue to push for a costly $2.4 billion “straw” for the greater St. George area[36] to pump 86,000 acre-feet of water 140 miles from the dwindling Lake Powell each year. According to the Utah River Council’s website, the controversial Lake Powell Pipeline would serve only 160,000 residents in St. George’s Washington County, and primarily for watering their lawns. Undoubtedly, much of Utah is not particularly drought-conscious. The Beehive state is ranked the second highest user of domestic water in the country at 178 GPCD (gallons per capita per day), nearly twice that of the national average of 82 GPCD.[37] Washington County municipal users, including St. George residents, consume an alarming 302 gallons per person per day on average, compared with 124 gallons on average for Los Angeles residents and 111 for Phoenix.[38]

Washington County, at the far eastern edge of the Mojave Desert, could eliminate the need for the Lake Powell Pipeline through common-sense water conservation measures such as Las Vegas’s turf-removal requirement implemented by the Southern Nevada Water Authority (SNWA) as a rebate program in 2021, which will save Las Vegas 9.3 billion gallons of water, or 30,000 acre-feet a year, according to the Sierra Club.[39] With both Lake Mead and Lake Powell hitting record-breaking low levels daily, this incongruous pipeline scheme dreamed up by growth-centric proponents is selfishly absurd. Not surprisingly, the pipeline has many detractors, including six compact states (Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada and Wyoming), which have officially opposed the project, along with many environmental groups, recreationists and conservationists. It seems, for now, that the pipeline’s future remains in a holding pattern.

While some in southeastern Utah make plans to siphon off more Colorado River water, some Lower Basin municipalities are working on weaning themselves off the supply with progressive conservation measures. For the record, San Diego receives 66 percent of its water from the Colorado River flows, Tucson 82 percent and Las Vegas 90 percent.[40] Southern Nevada used roughly 80 percent of its 300,000 acre-feet allocation during 2021. Water consumption was 80,000 acre-feet less that year compared to 2002 when the Las Vegas Valley had 800,000 fewer residents.[41] The SNWA, which serves 2.3 million people, completed a low-lake pumping station at the deepest part of Lake Mead in 2020 at the cost of $522 million to ensure a reliable and continued supply into the future—even if Lake Mead shrinks to dead-pool level.[42] Subsequently, by late April 2022, after the oldest of three intakes became exposed, plant engineers activated the new low-level new pumping station, which was not expected to go online for at least several years.

The SNWA is no stranger to controversy; former “water czar” Pat Mulroy, who headed the authority as its general manager from 1989 to 2014, pushed hard for the 300-mile-long Las Vegas Pipeline (as Nevadans dubbed it) to withdraw and convey fifty-eight billion gallons (about 180,000 acre-feet) of water annually[43] from ancient aquifer groundwater reserves in rural eastern Nevada for urban water users. Indigenous leaders, ranchers, environmentalists, outdoor recreationists, hunters, and rural community leaders of the region joined together as a coalition to fight this perceived water grab that threatened fragile springs, seeps and other ecologically sensitive habitats. After thirty-one years, the SNWA officially withdrew the project in April 2020 when it announced it would not appeal a previous District Court ruling barring the water district from its proposed “water mining” activities. Efforts to buy up eastern Nevada ranches with senior water rights began during the late 1980s under Mulroy’s watch, and the SNWA continues to hold these water rights. Although SNWA dropped the plans for the pipeline, the possibility of the authority leveraging these rights in the future remains.

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD) acts as the wholesaler to the California southland’s various water agencies and districts, including the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP). In total, MWD serves nearly nineteen million people throughout the region. MWD’s website states that 25 percent of the water distributed throughout its 5,200 square-mile service area comes from the Colorado River, 30 percent from the State Water Project in Northern California, and 45 percent from “local stormwater, groundwater, recycling and desalination.”[44]

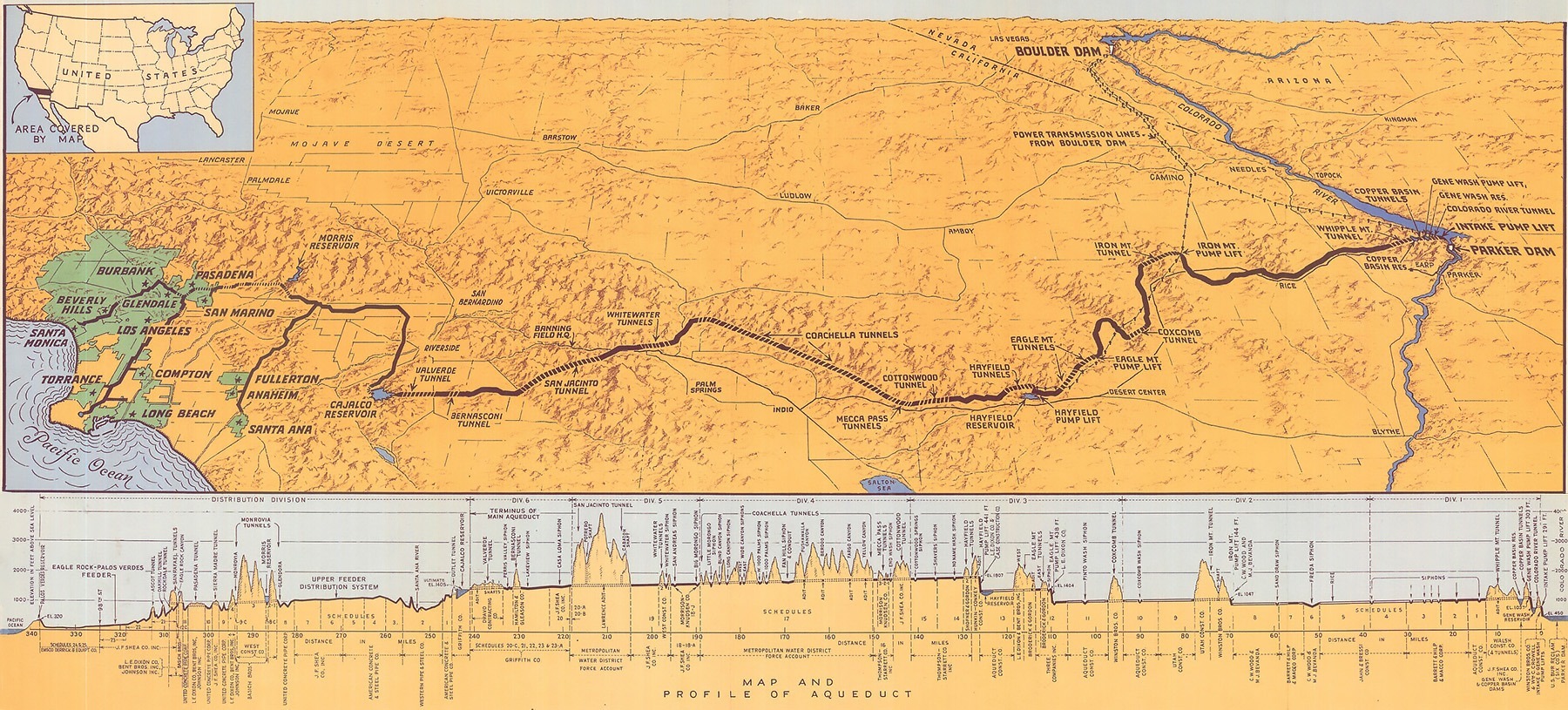

Map of the Colorado Aqueduct from The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, History and First Annual Report for the Period Ending June 30, 1938. F. E. Weymouth, General Manager and Chief Engineer, Los Angeles 1939. Wikipedia.

In 2021, MWD piped nearly one million acre-feet of water for consumptive use via the Colorado River Aqueduct, which originates at Lake Havasu’s Whitsett Intake.[45] A series of pumps and lifts transports the water across the Mojave Desert into the Coachella Valley, where it is piped adjacent to the San Andreas Fault through another series of lifts and tunnels, including one engineering marvel under Mount San Jacinto, to its terminus at Lake Mathews in Riverside County. Southern California’s largest consumer of Colorado River water is the aforementioned Imperial Irrigation District (IID), which consumed nearly 2.6 million acre-feet in 2021 for agriculture. The remaining 1.8 million acre-feet of California’s 4.4 million acre-feet annual allotment was distributed to tribal, agricultural, conservation, municipal and other stakeholders.[46]

While MWD has diversified its water sources to make its supply more resilient, more than half of the water it imports originates in California’s Sierra Nevada or the interior West’s Rocky Mountains. Water managers throughout the West depend on a sufficient year-to-year average snowpack in their respective ranges to feed their watersheds’ various streams and tributaries. Currently, California is suffering from continued severe to exceptional drought conditions—as is 93 percent of the western United States. The driest ten-year span ever recorded was from 2012 to 2021. Scientific tree ring reconstructions confirm that we live in one of the most severe drought periods occurring over the past 1,200 years and that human-driven climate change has worsened this megadrought event by 72 percent.[47]

On May 3, 2022, the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) announced two unprecedented drought-related emergency actions to prop Lake Powell levels to nearly one million acre-feet over the next twelve months. The first response releases 500,000 acre-feet of stored water from Wyoming’s Upper Basin Flaming George Reservoir. The second withholds 480,000 acre-feet from Powell’s annual release into Lake Mead of 7.48 million acre-feet to 7.00 million acre-feet as mandated by the 2022 Drought Response Operations Plan.[48] Still, these emergency drought measures are only a short-term solution.

On August 16, 2022, the BOR officially declared a Tier 2A Shortage Condition—the first time in Lake Mead’s history—initiating a series of drastic water delivery cuts and other conservation measures beginning January 2023, when the BOR’s August 2022 24-Month Study projected that Lake Mead will not reach above 1,050 feet in elevation.[49] There is a distinct chance the more drastic Tier 2B Shortage Condition could be triggered in 2024 if the lake’s level falls below 1,045 feet. If the BOR projects Lake Mead to drop under 1,030 feet at any time, Lower Basin states must convene with the BOR to implement an emergency strategy to keep levels above 1,020 feet. Although California will not experience mandated cuts under the 2022 Tier 2A declaration, Arizona, with its junior water rights, will be cut 592,000 acre-feet, or approximately 21 percent or of its 2023 apportionment. Nevada’s 2023 apportionment will be reduced by 8 percent and Mexico’s by 7 percent.[50]

Complicating this process is the argument that the 24-Month Study, which estimates inflows, reservoir elevations, releases to downstream users and anticipated power generation for the next two years, is often inaccurate, overly optimistic and does not take into account how increased aridification will impact the system over time. The BOR’s monthly reports are based on hydrologic models run by the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center using past inflow data recorded during a thirty-year reference period and updated every ten years.[51] Overall, the American West experienced a wetter climate during the 1990s than in the past twenty-two years. Current projections use streamflow data collected from 1991-2020 and are biased, resulting in forecasts that estimated higher lake levels in Lake Mead and Lake Powell than have actually occurred. A white paper published in February 2022 by the Center for Colorado River Studies at Utah State University examines how flaws in the BOR’s current system impact critical water management and policy decisions for the entire basin.

The Hemenway Marina at Lake Mead’s National Recreation Area has the only active boat launch for the 240-square-mile lake. The marina has been moved five times in 2022 to keep it within navigable waters. White mineral deposits on the landforms behind the marina mark the historic water line. Photo: Kim Stringfellow.

Even if regional growth suddenly ceases and water demand is kept at current levels, climate change will significantly diminish flows of surface water sources throughout the American West and beyond, likely sooner than later.

The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) found that warming temperatures or “hot drought” has contributed to about half the 16 percent decline in Colorado River flows during 2000 – 2017.[52] The USGS’s 2021 study estimates that for each additional one degree Celsius, or 1.8° Fahrenheit, that the Earth warms, the Colorado River’s average flow will decrease by 9.3 percent.[53] During the twentieth century, from 1913 to 2017, with the average temperature increasing by 1.4° C or 2.5° F, the Colorado’s average flow decreased by about 20 percent. The USGS models estimate that by 2050, the average flow will be reduced an additional 14 percent to 31 percent.[54]

The Upper Basin contributes, on average, about 92 percent of the entire basin’s natural streamflow every year, with Rocky Mountain headwater snowmelt as its primary source. As the winter season progressively shortens, snowpacks are melting faster and sooner, resulting in rapid runoff over a few weeks rather than months. Along with this trend is a shift from snow to rain—areas that previously received substantial snowfall are now receiving rainfall, in turn creating the possibility of intensified flooding.

Projected rises in precipitation aren’t expected to make up for the loss of the Upper Basin snowpack due to warming temperatures. This is compounded by the snowpack’s decreasing ability to reflect solar radiation into space, known scientifically as albedo. Essentially, as the planet warms, we accelerate a crucial natural system’s power to deflect global warming worldwide.

Researchers have found that increased dust in the atmosphere emanating from surrounding areas undergoing aridification leads to an escalated heat load in the snowpack. This occurs as airborne particulates settle, causing snowpacks to melt all at once. Temperature-induced drying of soils adds more complications to this cycle. The dry, compacted soil cannot absorb water. This leads to soil erosion, changes in the healthy biome of the soil and consequent desertification, affecting the entire ecology of the system.

Rising temperatures and lack of moisture make climate-stressed forests increasingly susceptible to disease, resulting in an extended, broader and more intensified wildfire season—something that everyone in the American West is acutely aware of. All these combined climate-induced impacts will permanently alter the Colorado River Basin’s hydrology and ecology for the worse. Even if humans collectively stopped pumping greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere, temperatures will continue to steadily increase in the future.[55] The essential takeaway for the reader is that severe water shortages will also occur in the near future.

A view of Black Rock Canyon from Hoover Dam looking west in 2018. Photo: Kim Stringfellow.

On June 14, 2022, BOR Commissioner Camille Calimlim Touton responded to Congress before the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. In her written testimony, she stated, “Water supplies for agriculture, fisheries, ecosystems, industry, cities, and energy are no longer stable given anthropogenic climate change, which threatens food and energy security, human health, the regional economy, and biodiversity.” Touton more pointedly expressed during the live hearing that “The challenges we are seeing today are unlike anything we have seen in [the Bureau’s] history…hydrological variability, hotter temperatures leading to earlier snowmelt, dry soils all translating to earlier and low runoff…this is coupled with lowest reservoir levels on record. A warmer, drier West is what we are seeing today.”[56]

Touton’s most stunning announcement stipulated possible water delivery cuts of two to four million acre-feet by the end of the year to address anticipated “critically low water levels” expected during 2023. Consider that Arizona used 2.4 million acre-feet in 2021 and that Commissioner Touton’s high-end demand equals nearly all of California’s annual apportionment. When Senator Mark Kelly (D-Arizona) asked Touton to clarify whether these cuts would be made multilaterally without regard to river priority—essentially shattering the 120-year-old Law of the River—Touton swiftly responded, “Yes, we will protect the system.” The gravity of the situation is apparent.

We are 150 feet from twenty-five million Americans losing access to the Colorado River, and the rate is accelerating. –John Entsminger, General Manager, Southern Nevada Water Authority.

SNWA’s current general manager John Entsminger followed Touton’s announcement with his own telling observation, “What has been a slow-motion train wreck for twenty years is accelerating and moment of reckoning is near. While the situation is objectively bleak, is it not, in my view, unsolvable…There’s little we can do to improve the Colorado River’s hydrology. The solution to this problem is a degree of demand management previously deemed impossible.”

With the 2019 DCP expiring in 2026, water managers, policymakers, Tribes and the general public must be realistic about the Colorado River’s limitations. The August 16, 2022, BOR press release reinforced Commissioner Touton’s demand for conservation over the next four years, stating that additional conservation between 600,000 and 4.2 million acre-feet is required to stabilize both reservoirs. Additionally, the press release stated that when the current DCP agreement expires, the BOR will authorize annual release reductions from Lake Powell of seven million acre-feet and below, when necessary, leaving the Lower Basin and Mexico to locate or conserve the additional two to three million acre-feet of water it has been dependent on.

Indeed, a societal paradigm shift is necessary as our collective existential future in the American Southwest is under threat. In the meantime, the seven states that depend on the river failed to come up with emergency drought reductions by the mid-August 2022 deadline, which likely will lead to years of legal entanglements that John Wesley Powell had so precisely forewarned. Bruce Babbitt and many others are calling for the Colorado River Basin to be managed as a whole instead of as two artificially separated basins to facilitate sound and equitable water management decisions in a future with less fresh water.[57]

In a June 16, 2022, op-ed in The Salt Lake Tribune, Babbitt and Brian Ritcher, President of Sustainable Waters, commented, “We are relentlessly plundering the water stored in Lake Mead and Lake Powell to compensate for mounting water deficits. As these reservoirs—now nearly three-quarters depleted—continue falling toward dead pool, water bankruptcy awaits….As the crisis deepens, these short-term patches will no longer suffice. The only way to secure the future is to devise a long-term plan to balance our accounts, to withdraw and use only that amount of water the river provides each year.” Babbitt and Ritcher note in their op-ed that Lower Basin states have done a poor job of reducing their annual water use by 1.4 million acre-feet to meet the 2019 DCP mandate. They report that withdrawals from Lake Mead have only been reduced by 533,000 acre-feet in the past years. The Upper Basin’s report card isn’t much better—it has yet to agree on cuts or even set reduction targets.[58]

The current crisis is of a magnitude that water managers and policymakers have yet to reckon with—but the challenge is not insurmountable. Meeting that challenge will require cooperation and collaboration between all basin stakeholders to realistically and equitably agree to embrace innovative water conservation measures on a scale not previously imagined. Fortunately, the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act earmarks $4 billion to address the Colorado Basin megadrought. California Governor Gavin Newsom slated $8 billion beginning in 2019 for drought relief efforts to modernize the state’s existing water infrastructure over the coming years. These new climate-resilient solutions won’t replicate the Bureau’s model of monumental dam-building and water-storage projects of the past. Instead, localized water recycling, desalinization, capture and conservation projects will lessen the demand for imported water. This includes ramping up and improving existing infrastructure to capture stormwater runoff and treat it for direct recycling or groundwater recharge for future use. Newsom’s August 2022 plan’s goal is to create four million acre-feet of water storage across the state “to capitalize on big storms when they occur and store for drier periods.”[59] According to LADWP’s 2015 Urban Water Management Plan, the department currently charges 64,000 acre-feet of stormwater each year, but most of it continues to flow to the Pacific Ocean. LADWP’s goal is to double this amount to 132,000 acre-feet in a conservative scenario and up to 178,000 with more aggressive action by 2035.[60] To compare, the LADWP imports 314,000 acre-feet or 57 percent of its total annual water supply, from the Colorado River.[61]

Lake Mead previously covered the entire expanse of Las Vegas Bay, including the land in the foreground. The Las Vegas Wash, carrying stormwater, urban runoff and treated wastewater from Las Vegas Valley, empties into the bay contributing approximately two percent of water for Lake Mead. Photo: Kim Stringfellow.

In Las Vegas, all stormwater flows into the Las Vegas Wash, along with highly treated effluent, urban runoff and shallow groundwater. About 200 million gallons of water daily is carried into Lake Mead, contributing about two percent of its water. The remediated wetlands filter this reclaimed water as it travels fifteen miles into Las Vegas Bay while providing a natural habitat for native vegetation and wildlife. SNWA reclaims nearly 100 percent of its indoor-generated wastewater for either direct or indirect use as return-flow credits. According to SNWA, indoor water use consumes approximately 40 percent of its Colorado River allotment. SNWA is working to limit outdoor water use further. In July 2022, announced limits to new construction residential swimming pool sizes were expected to save thirty-two million gallons of water over the next ten years.

Another water-saving measure not currently being considered could be to require compact gray water filter systems for new homes and businesses to reuse household-generated gray water for flushing toilets. Currently, 24 percent of an average American’s consumptive water use goes down the toilet.

Others propose multi-problem-solving large-scale water efficiency projects. For instance, installing floating solar photovoltaics or “floatovoltaics” on six percent of Lake Mead could generate 3,400 megawatts of electricity while substantially reducing water loss to evaporation, at the same time increasing solar panel efficiency by keeping the panels cooler.[62] A 2021 study by engineers at the University of California Merced shows how covering all 4,000 miles of California’s open canals with solar panels would save more than sixty-five billion gallons of water annually by reducing evaporation while generating thirteen gigawatts of electricity, which is about half the target for renewable energy California needs to meet its clean-energy goals by 2045.[63] The apparent takeaway for desert conservationists is that less ecologically vital desert habitats would need to be developed for less-efficient industrial solar arrays within Southwestern deserts.

The progressive outlook is a future where development in the Upper Basin is slowed or even curtailed altogether, with great sacrifices made to conserve water in the Lower Basin. However, a divisive conflict will surface if the Lower Basin agrees to implement severe conservation measures but the Upper Basin increases its consumptive use with new pipelines and other development schemes that promote growth and increase low-value agriculture.

Indeed, Entsminger pointed out during the June 2002 Senate hearing that 80 percent of Colorado River water is used by the agricultural sector. Of that, 80 percent is used to grow heavy-water-use crops such as alfalfa to feed livestock—some of which is cultivated to retain the farmers’ water rights. The Upper Basin primarily produces low-value forage crops due to the limitations of its cooler, high-elevation geographical location. Plus, agriculture in this region is heavily subsidized by taxpayers and produces far less gross domestic product than the Lower Basin. A July 2022 paper published in the journal Science states, “The Lower Basin irrigates less than half the area irrigated by the Upper Basin, yet its agricultural sales are more than three times that of the Upper Basin.”[64]

Furthermore, the Lower Basin supplies high-value vegetables, fruits, tree nuts and field crops that feed the nation and abroad year-round. This is due to fertile soils of lower elevation of Southern California and Arizona farms that allow for a more productive growing season due to warmer, frost-free weather than in the Upper Basin. According to a 2013 Pacific Institute report, if six percent of farms growing low-value legacy crops are paid not to do so, this could free up 600,000 acre-feet of water annually throughout the basin. It is therefore a given that compensated agricultural water transfers from both the Upper and Lower Basins will be a significant part of reducing water use for the successful rollout of the new 2026 DCP. Still, it remains acutely evident that the Colorado River’s supply is finite—so future conservation must be practiced by all parties involved.

Had the participants of the 1893 Second Irrigation Congress taken heed of Major Powell’s sound and visionary judgment, we might be at a very different point in time. As historian Donald Worster sees it, “the river would have remained largely unutilized and unharnessed along most of its course if Powell’s dream of the West had prevailed.” But Powell understood how greed and the desire to dominate nature are part of the core human drive. His retort was, “Who rules this West you have built? Not the people, but the large-scale capital and large-scale expertise,” and that—for better or worse—has become our legacy.

This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] Donald Worster, “Landscape with Hero: John Wesley Powell and the Colorado Plateau,” Southern California Quarterly, Vol. 79, No. 1 (Spring 1997): 29.

[2] “John Wesley Powell and Native American (SIA-2002-10682),” Smithsonian Institutional Archives, accessed August 15, 2022, https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_sic_10061. The summary for the photograph states, “During his years as explorer and surveyor, John Wesley Powell made great effort to gain the trust of the native Americans he came into contact. He compiled vocabularies, collected details of religion and lore of Indian peoples, and championed the rights of Native Americans. When Congress created the Bureau of Ethnology in 1879, Powell was named its first director (1879-1902), a post he held until his death.”

[3] For further reading see: Wallace Stegner, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1954).

[4] Donald Worster, A River Running West: The Life of John Wesley Powell (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 352.

[5] Major tributaries within the Colorado River Basin include the Colorado, Gila, Green, Gunnison, Little Colorado, Salt, San Juan, San Pedro, Santa Cruz, Virgin and Yampa rivers. About 90 percent of the Colorado River’s flow originates in the Upper Basin.

[6] Charles V. Stern and Pervaze A. Sheikh, “Management of the Colorado River: Water Allocations, Drought, and the Federal Role (R45546),” Congressional Research Service, April 10, 2022.

[7] For more information on this topic, see Ian James, “Where the Colorado River no longer meets the sea, a pulse of water brings new life,” Los Angeles Times, June 23, 2022.

[8] Elevation data for Lake Mead and Lake Powell provided by https://lakemead.water-data.com and https://lakepowell.water-data.com, accessed August 15, 2022.

[9] Eric Kuhn and John Fleck, Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2019), 210.

[10] 5-Year Probabilistic Projections, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, accessed August 15, 2022, https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/riverops/crss-5year-projections.html.

[11] Arizona refused to ratify the agreement until 1944, thus green-lighting the Central Arizona Project, which began construction in 1973.

[12] An acre-foot covers an acre of land with one foot of water, equivalent to roughly 326,000 gallons or 43,560 cubic feet of water. One-acre foot of water will serve approximately three Southern California families per year.

[13] The 1944 treaty agreement provided Mexico with 1.5 million acre-feet of water annually.

[14] Between 1906 and 2020, river gauge measurements at Lees Ferry averaged 14.7 million acre-feet per year. Stern and Sheikh, “Management of the Colorado River,” 1.

[15] Since 2000, the naturalized flow of the Colorado River has varied substantially from year to year. For example, in 2002, the flow at Lees Ferry was only 6,023,485 acre-feet. In 2011, it was 20,302,681 acre-feet. A Future on Borrowed Time: Colorado River & the New Normal of Climate Change (public review draft), Utah Rivers Council, 2021, 4.

[16] USGS hydrologist E.C. LaRue, tasked with measuring the average “natural” flow of water from the Colorado River Basin during the 1910s, determined the river’s average natural flow to be fifteen million acre-feet each year. His analysis considered drought data from the latter part of the nineteenth century. In contrast, the Bureau of Reclamation’s stream gauge records began with the unusually wet years during the first two decades of the twentieth century. LaRue’s 1916 Water Supply Paper 395 starkly concluded that “the flow of Colorado River and its tributaries is insufficient to irrigate all of the irrigable lands lying within the basin.” LaRue’s analysis and two later government reports, one by USGS scientist Herman Stabler and another Congressional panel headed by William Sibert, made similar projections available to the compact planners before the final ratification in 1928 but were dismissed. LaRue and the other projections were later confirmed with scientific tree ring studies. Kuhn and Fleck, Science Be Dammed.

[17] The upper cofferdam was constructed before the river was diverted to protect the construction site and workers from flooding.

[18] The filling of Lake Mead began on February 1, 1935, before the dam’s completion.

[19] Six Companies, Inc. was a joint venture of industrialists that included Henry J. Kaiser and W.A. Bechtel.

[20] From 1999 to 2015, Arizona’s consumptive use of Colorado River water dropped to 2.6 million acre-feet. In 2021, Arizona used 2.4 million acre-feet. Source: Lower Colorado River Water Accounting, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, accessed August 15, 2022, https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/wtracct.html.

[21] Drew Kann, Renée Rigdon and Daniel Wolfe, “The Southwest’s most important river is drying up,” CNN, August 21, 2021, accessed August 15, 2022, https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2021/08/us/colorado-river-water-shortage.

[22] Because part of Arizona is within the Upper Basin, the state additionally receives 50,000 acre-feet of Colorado River water annually.

[23] About 66 percent of San Diego’s water comes from the Colorado River. Kann, Rigdon and Wolfe, “The Southwest’s most important river is drying up.”

[24] For further reading, visit Kim Stringfellow’s Greetings from the Salton Sea at https://greetingsfromsaltonsea.com.

[25] The IID’s consumptive use was about 2.5 million acre-feet in 2021.

[26] “Indian Water Rights Settlements (R44148),” Congressional Research Service, April 16, 2019.

[27] CRIT includes Chemehuevi, Hopi, Mojave and Navajo tribal members.

[28] “The Status of Tribal Water Rights in the Colorado River Basin (Policy Brief #4),” Water & Tribes Initiative: Colorado River Basin, Center for Natural Resources & Environmental Policy, University of Montana, April 9, 2021. For further reading, visit https://www.naturalresourcespolicy.org/projects/water-tribes-colorado-river-basin/default.php.

[29] Federally recognized Indian tribes within Mojave Desert region with substantial Colorado River water rights include the Chemehuevi Indian Tribe, Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT), Fort Mojave Indian Tribe, Hualapai Indian Tribe, Las Vegas Tribe of Paiute Indians, Moapa Band of Paiute Indians, and the Shivwits Band of Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah (Constituent Band of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah).

[30] Colorado River Accounting and Water Use Report: Arizona, California and Nevada, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Calendar Year 2021, 5, https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/g4000/4200Rpts/DecreeRpt/2021/2021.pdf.

[31] John Fleck, “The question of reservoir evaporation–How much water are the Lower Colorado River Basin states really using?” JFleck at Inkstain, October 2020, http://www.inkstain.net/fleck/2020/10/the-question-of-reservoir-evaporation-how-much-water-are-the-lower-colorado-river-basin-states-really-using.

[32] “Estimates of Evapotranspiration and Evaporation along the Lower Colorado River,” U.S. Department of the Interior, 2020, https://eros.usgs.gov/doi-remote-sensing-activities/2020/bor/estimates-evapotranspiration-and-evaporation-along-lower-colorado-river.

[33] A Future on Borrowed Time, 7. Stern’s and Sheikh’s Congressional Research Service report R45546 cited in footnote #14 states the Colorado River’s annual average natural flow from 1906-2020 as 12.6 million acre-feet. In contrast, Utah River Council states 12.4 million acre-feet.

[34] A Future on Borrowed Time, 8.

[35] A Future on Borrowed Time, 8.

[36] Technically, St. George, Utah—while administratively considered in the Upper Basin lies geographically within the Lower Basin drainage region, but the pipeline plans to source water from its Upper Basin apportionment.

[37] Mark Milligan, “Glad you asked: Does Utah really use more water than any other state?” Utah Geological Survey, May 2018, accessed August 15, 2022, https://geology.utah.gov/map-pub/survey-notes/glad-you-asked/does-utah-use-more-water.

[38] “Washington County Water Conservation,” Utah Rivers Council, accessed August 15, 2022, https://utahrivers.org/pipeline-alternatives.

[39] Daniel Rothberg, “Could Las Vegas’ grass removal policies alter the Western US drought-scape?” Sierra, July 24, 2021.

[40] Kann, Rigdon and Wolfe, “The Southwest’s most important river is drying up.”

[41] Kann, Rigdon and Wolfe, “The Southwest’s most important river is drying up.”

[42] “Low lake level pumping station,” Southern Nevada Water Authority, accessed August 15, 2022, https://www.snwa.com/our-regional-water-system/low-lake-level-pumping-station/index.html.

[43] Eric Siegel, “Killing the Las Vegas Pipeline,” High Country News, September 18, 2020.

[44] “Our Foundation: Securing Our Imported Water Supplies,” The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, accessed August 15, 2022, https://www.mwdh2o.com/securing-our-imported-supplies.

[45] See footnote #31.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Stephanie Elam, “Lake Mead plummets to unprecedented low, exposing original 1971 water intake valve,” CNN, April 29, 2022.

[48] “Drought Response Operations Agreement,” U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, accessed August 15, 2022, https://www.usbr.gov/dcp/droa.html. The 2007 Interim Guidelines established the operational framework for the Upper and Lower basin Drought Contingency Plans (DCP), which expires in 2026.

[49] The BOR’s 24-Month Study “Operation Plan for Colorado River System Reservoirs,” published monthly, outlines how Lake Powell and Mead are managed during the upcoming water year and are announced in the mid-August report. The August 2022 24-Month Study projects Lake Mead’s 2023 operational elevation at 1,047.61 feet, buoyed by the 480,000 acre-feet withheld in 2022.

[50] “Interior Department Announces Actions to Protect Colorado River System, Sets 2023 Operating Conditions for Lake Powell and Lake Mead,” Bureau of Reclamation, August 16, 2022, https://www.usbr.gov/newsroom/#/news-release/4294.

[51] Input data from the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center includes observed snowpack, soil moisture, anticipated precipitation and temperature.

[52] Ian James, “Rising temperatures are taking a worsening toll on the Colorado River, study finds,” AZ Central, February 22, 2020. Visit https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/arizona-environment/2020/02/22/global-warming-rising-temperatures-worsening-toll-colorado-river-climate-change/4832434002/ for an informative video feature accompanying this article.

[53] P.C. D. Milly and K.A. Dunne, “Colorado River flow dwindles as warming-driven loss of reflective snow energizes evaporation,” Science, Vol. 367, No. 6483 (February 20, 2020): 1252-1255.

[54] James, ““Rising temperatures are taking a worsening toll on the Colorado River.”

[55] Richard B. Rood, “If we stopped emitting greenhouse gases right now, would we stop climate change?” The Conversation, July 4, 2017.

[56] “Full Committee Hearing To Examine Short And Long Term Solutions To Extreme Drought In The Western U.S.,” Senate Committee on Energy & Natural Resources,” June 14, 2022.

[57] Kevin G. Wheeler, Brad Udall, Jian Wang, Eric Kuhn, Homa Salehabadi, John C. Schmidt, “What will it take to stabilize the Colorado River?” Science, July 21, 2022, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abo4452.

[58] “Bruce Babbitt and Brian Richter: Saving the Colorado River,” The Salt Lake Tribune, June 16, 2022.

[59] The Arizona Department of Water Resources states that “Arizona has stored nearly three trillion gallons of water for future use.” “Arizona Water Facts,” accessed August 16, 2022, https://www.arizonawaterfacts.com/water-your-facts.

[60] “Los Angeles Department of Water & Power Urban Water Management Plan 2015,” LADWP, 222.

[61] “Metropolitan Water District of Southern California,” LADWP, accessed August 15, 2022, https://www.ladwp.com/ladwp/faces/ladwp/aboutus/a-water/a-w-sourcesofsupply/a-w-sos-metropolitanwaterdistrictofsoutherncalifornia.

[62] Philip Warburg, “Floating Solar: A Win-Win for Drought-Stricken Lakes in U.S.,” Yale Environment 360, June 29, 2016.

[63] Roger Bales, “First solar canal project is a wind for water, energy, air and climate in California,” The Conversation, February 22, 2022.

[64] Kevin G. Wheeler, et al. “What will it take to stabilize the Colorado River?”