The weird solitude, the great silence, the grim desolation, are the very things with which every desert wanderer eventually falls in love. You think that strange perhaps? Well, the beauty of the ugly was sometime a paradox, but to-day people admit its truth; and the grandeur of the desolate is just paradoxical, yet the desert gives it proof. –John C. Van Dyke, The Desert, 1901

In 1898 John C. Van Dyke embarked on a journey that would forever change and color how we view the arid expanses of the American Southwest. His adventure chronicled in The Desert: Further Studies in Natural Appearances has been a popular and enduring classic from its first publication in 1901. In continuous print for over 100 years, this pivotal book is largely credited with shifting our perception of desert regions of the West. Once deemed “God’s mistake” and the “Devil’s Domain,” deserts were largely considered to be uninhabitable wastelands that only a few rugged souls could navigate or be lucky enough to eke out some sort of meager living within. Although a few dissenting voices sang restrained praises for these dry, desolate hinterlands, the general public considered this barren and otherworldly landscape overtly hostile due to the popular mid-nineteenth century accounts of unfortunate individuals that had attempted to cross the desolation of Death Valley and similar terrain.

To gain an understanding of how these former and perhaps ongoing associations came into play, it is helpful to refer to the origins of the word desert. The Online Etymology Dictionary states that the twelfth and thirteenth-century European definition of the word translates into wasteland, evolving from Late Latin desertum (source of Italian diserto, Old Provençal dezert, Spanish desierto), literally meaning “thing abandoned.” In colonial times desert shifted in meaning somewhat, referring to lands uninhabited and treeless but not necessarily arid, as they are defined today.

In contrast, the ancestral desert peoples of the Mojave, Colorado and Great Basin deserts consider the concept of desert as wasteland inconceivable and unfamiliar. For the Timbisha Shoshone of Death Valley, this living desert provided everything necessary to thrive—they hunted and harvested foodstuffs seasonally, including seedpods from the native honey mesquite groves they carefully managed in the valley, a place that they have resided “since the beginning of time.”[2]

The original concept of the “Great American Desert,” a title coined in 1806 by explorer Lieutenant Zebulon Pike, was made popular by cartographer/explorer Major Stephen H. Long in 1821. Curiously, Long mapped out what is geographically considered today to be part of the Great Plains—those lands east of the Rocky Mountains but west of the Mississippi River. The true “Great American Desert”—the Great Basin—was at this time familiar to only a handful of hardy explorers and trappers of European descent and the varied Indigenous peoples who called these regions home. Encouraged by boosters of the westward expansionism who had reframed these lands as an “idyllic agrarian paradise” in their efforts to encourage settlement, this particular myth was put to rest when hordes of emigrants began heading westward during the late 1850s and ’60s, saw the American prairie firsthand (noting how it differed drastically with the authentic desert located further West) and began staking their claim.

How we continue to see, interpret and value the Desert West is largely dependent and collectively conditioned through other cultural frameworks, including religious attitudes, economic valuation and aesthetic appreciation. The perceived benefit for humans in terms of resources the desert provides or as a place for spiritual renewal and contemplation also colors our overall appraisal.

The word desert, coded and synonymous with the term wasteland is a difficult association to dispel, even when we are presented with opposing scientific research or when personal observation shows us otherwise. Although collective attitudes toward arid landscapes have indeed changed drastically over time, the concept of desert as wasteland continues to persist largely due to our own personal desires and projections, but also religious and other ideological beliefs that are deeply ingrained within our nation’s most cherished institutions as well as our own personal psyches.

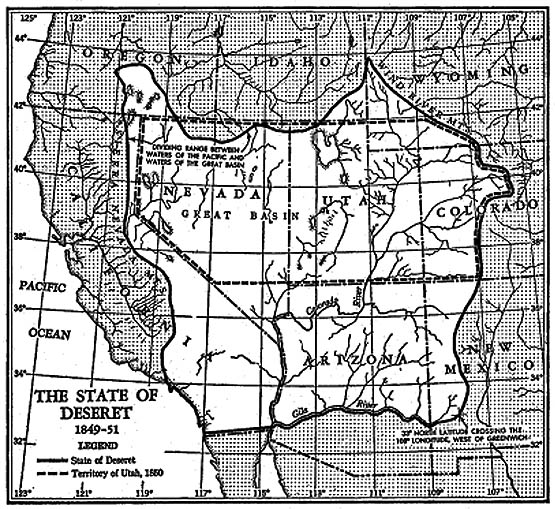

The State of Deseret (1849-51) from Holman Hamilton’s “Prologue to Conflict: The Crisis and Compromise of 1850.”

Making the desert bloom

Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth. Genesis 1:28 (King James version)

It is a given that Judeo-Christian ideology permeates “manifest destinarianism,” but it is less apparent that some of its more problematic tenets continue to influence state and federal land management and resource policies throughout the West. Consider the siting of Mojave Desert’s numerous military reservations, bombing ranges, the proposed nuclear waste repositories or the current rash of federally subsidized massive “green” industrial solar and wind projects that are now sited, or scheduled to be, deep within the Mojave and Colorado deserts where there’s “nothing there.”[3] Looking back at the last century’s monumental hydrological projects engineered and constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation, along with the Army Corps of Engineers, to harness the power of the Colorado, Columbia and other wild rivers of the West, it is difficult to not see this narrative buried in the foundations of these dam(n) sites. Both Lynn White Jr.’s controversial 1966 essay, The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis, along with the nonfiction essays of author/conservationist Wallace Stegner and others point to anthropocentrism and a one-sided mindset fostered through extreme literal interpretations of Genesis 1:28 that have, in part, led us to control and exploit the planet for human benefit alone. To be fair, more moderate interpretations of Genesis 1:28 suggest that this passage provides a stewardship model rather than one of dominion.

In his essay “Striking the Rock,” Stegner argues that Genesis 1:28 has indirectly sanctioned some of our most reckless engineering endeavors designed to control and placate wild nature.[4] In the opinion of this writer that is not so farfetched. For example, Stegner points out that in the Mormons’ quest to make the Promised Land of the “desert blossom as the rose,” the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) were hands-down the most prodigious in their drive to accomplish this God-given task.

Consider their somewhat failed attempt in 1849 to create the provisional LDS Deseret state/sanctuary across the American Southwest, or the rallying call of this LDS church elder during the early twentieth-century irrigation campaigns: “The destiny of man is to possess the whole earth; the destiny of the earth is to be subject to man. There can be no full conquest of the earth, no real satisfaction to humanity if large portions of the earth remain beyond his highest control.”[5]

It is interesting to note that this literal Bible-driven rush to “Green the Desert” worldwide continues today, with bizarre livestock grazing proposals by the likes of biologist Allan Savory who seems to group together both richly complex desert ecosystems along with grasslands terribly blighted with human-induced desertification. In his quest to do so, Savory considers our planet’s diverse arid lands as places that must be “greened” to support more of the same activities—rampant development, overgrazing of livestock and overall poor management of area resources that the majority of conventional researchers feel are destroying these areas in the first place.[6]

Although not necessarily connected in theory or practice with Savory’s hypothesis, the modern Permaculture movement shares some remote philosophical leanings with Savory in its pursuit to green the desert and harvest water in extreme arid landscapes. The urge to manipulate our arid landscapes into productive ones that serve humankind is at times necessary, but our lack of desire to accept our diverse and wonderfully complex desert ecosystems in their natural state is equally disturbing.

When reading The Desert the contemporary reader is struck by the flagrant religious overtones sprinkled throughout Van Dyke’s text. Considering the post-Victorian era in which it was penned and Van Dyke’s standing as a prominent man of letters, the language is quite normal and expected. Take into account that the well-educated Van Dyke began his career as a theological seminary librarian and later became Rutgers’ first art historian, whose refined “Art for Art’s Sake” outlook gave him entry to socialize in the most elite and privileged circles of his day; he could claim a close alliance and friendship with industrialist, and not so environmentally friendly, Andrew Carnegie whom he dedicated The Desert to, if only by his initials, “A.M.C.”

Surprisingly, Van Dyke and his five brothers spent their teens in rural Wabasha, Minnesota, after their father had moved the family from their upscale residence in Brunswick, New Jersey, to a region “just emerging from its wild frontier days.”[7] In his autobiography, Van Dyke claims that he was “mentored by ‘wild’ Sioux Indians and the rough-and-ready characters of the border region.”[8] However, scholars such as Peter Wild are skeptical of this inflated assertion. Still, it seems that the young Van Dyke learned to admire and respect wilderness and wild spaces during his tenure in outback Minnesota. Indeed, a fan of the author much later described him active as “both an indoorsman and outdoorsman.”[9]

Curiously, Van Dyke did not actually make it out to the Desert West until he was forty-three years old. Both he and his older brother Theodore suffered from an unknown respiratory ailment, and in years prior, Theodore had “gone native” and relocated to a ranch near the rough-and-tumble mining town of Daggett in the center of the Mojave Desert, just east of Barstow. Encouraged by his brother’s recovery, Van Dyke sought out the dry climate of the desert. A respected naturalist, author, rancher, all-around outdoorsman and Daggett’s justice of the peace, Theodore Strong Van Dyke prided himself as a personal friend and colleague of soon-to-be president Theodore Roosevelt and naturalist John Muir. Muir, it turns out, stayed at the ranch often throughout his later years to attend to his sickly daughter Helen, having sent her there in 1907 to recuperate.[10]

It is known that Van Dyke spent considerable time at Theodore’s ranch and also traveled extensively through the Colorado and Sonoran deserts into Arizona and northern Mexico, and across stretches of the Mojave and Great Basin deserts. Still, the actual dates and routes traveled are rather murkily documented. Scholars have attempted to retrace his solitary journey (with only a pony and his dog Cappy for companions) through his autobiography. In doing so they have surmised that much of Van Dyke’s literary adventure was largely fabricated as a series of embellished, fictionalized accounts created from secondhand sources or even his brother Theodore’s own papers and journals.

Several books and papers by Wild—who has called Van Dyke the “Southwest’s Plaster Saint wandering the deserts”—along with others cite “apparent falsehoods and inconsistencies” when scrutinizing flora and fauna described by Van Dyke in the varying desert regions where he supposedly traveled. Wild (with Neil Carmony) continues to remind the reader that “The Desert is an aesthetic celebration of the Southwest, a poetic description of its beauties and not a journalistic record of its author’s travels.”[11]

Wild and Carmony propose in The Trip Not Taken that “Van Dyke saw the wonders of the Southwest not from horseback, but through the windows of trains and hotels and from the porch of his brother’s California desert ranch.”[12] Nevertheless, one cannot deny that Van Dyke appears to have spent enough time in the desert to strongly oppose its exploitation as suggested in the following quote:

The deserts should never be reclaimed. They are the breathing-spaces of the West and should be preserved forever.

Did Wild feel hoodwinked by his desert literary hero? Perhaps. His later essays focusing on the author seem to point to a determined desire to expose Van Dyke as a dilettante for leading his audience on. Because Wild is no longer here to debate the subject, it is not fair to conjecture. Regardless, we cannot argue Van Dyke’s remarkable contribution to desert literature, how it changed the way many of us now view the desert. Van Dyke revealed to us, through his painterly prose, the desert’s inherent value, not through the various resources the desert provides us, but for what it is in spite of our desire to improve, modify, exploit or marginalize its wondrous gifts. His seminal book forever shifted the desert-as-wasteland epithet into something more positive. Even if some unenlightened individuals still equate arid lands with “barrenness, desolation, emptiness and wasteland,” we now know that this is simply not the case.

This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Support us with your tax-deductible donation.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] Peter Wild, The Opal Desert: Explorations of Fantasy and Reality in the American Southwest (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1999), 2.

[2] The Mesquite Traditional Use Pilot Project is a current imitative managed by Timbisha tribal members and Death Valley National Park personnel, whose goal is to restore this traditional food source on tribal holdings in Death Valley National Park.

[3] In the 2014 documentary DamNation, Floyd Dominy (commissioner of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation from 1959–1969) states that there was “nothing there…nothing there,” when reflecting on impacts (human or otherwise) of the Colorado River’s Glen Canyon Dam on the surrounding ecosystem.

[4] For further reading see: Wallace Stegner, “Striking the Rock,” Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs (New York: The Modern Library, 2002). See also: Marc Reisner’s Cadillac Desert and Donald Worster’s Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and the Growth of the American West. It is interesting to note that Salt Lake City’s main newspaper is the Deseret News.

[5] John Widtsoe, Success on Irrigation Projects (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1928), 138. This sentiment is echoed by Floyd Dominy in DamNation when he states, “I’ve changed the environment, yes, but I’ve changed it for the benefit of man.”

[6] For further reading: Chris Clarke, “TED Talk Teaches Us to Disparage the Desert,” KCET: Social Focus, March 15, 2013, https://www.kcet.org/socal-focus/ted-talk-teaches-us-to-disparage-the-desert.

[7] Peter Wild, John C. Van Dyke: An Essay and a Bibliography (Tucson: The University of Arizona Library, Arizona Board of Regents, 2001).

[8] Wild, John C. Van Dyke.

[9] Peter Wild and Neil Carmony, “The Trip Not Taken: John C. Van Dyke, Heroic Doer or Armchair Seer?” The Journal of Arizona History 34, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 71.

[10] Peter Wild, “John Muir and the Desert Connections,” John Muir Newsletter, 5, no. 2, (Spring 1995). Although John C. Van Dyke refers to meeting Muir in his autobiography, it is not known if they were more than acquaintances. In his memoir, Theodore’s son Dix does mention that “the two [John C. Van Dyke and Muir] wrangled incessantly.”

[11] Wild, “John Muir,” 70.

[12] Wild, “John Muir,” 77.

The State of Deseret map shown on page 106 is from Holman Hamilton’s Prologue to Conflict: The Crisis and Compromise of 1850 (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2005). Lead photo: Timothy O’Sullivan, Desert Sand Hills near Sink of Carson, Nevada, 1867. The J. Paul Getty Museum.