From space, the far western portion of the Mojave Desert resembles a giant arrow pointing towards the Pacific. Flanked by the San Gabriel Mountains and the San Andreas Fault at its southern end, with the Tehachapi Mountains climbing upward to the northwest, the desert’s western boundary is distinctly delineated. Within this geographic arrowhead, the Antelope Valley abuts and merges into northern Fremont Valley; the former is referred to as “North Los Angeles County” and the latter a part of Kern County.

The landscape of the Antelope Valley has undergone a dramatic transformation due to exponential growth and development over the last forty years. In the 1980s, the area began shifting from a sparsely populated, mostly white, high-desert outback to a bustling “bedroom commuter colony,” allowing those priced out—including many people of color—to purchase newer, single-family homes.

Now 71,000 Antelope Valley residents commute daily into the greater Los Angeles area for work.[1] But as the region’s landscape is modified and its demographics shift, the arid land is revealing something potentially threatening to the health of those who came here to escape the high cost of living and other urban woes of “down below.”

Long before Palmdale and Lancaster commuters began their grueling ninety-minute-plus drives to work, varied groups of migratory Paleoindians occupied the region at least 11,000 years ago. These aboriginal peoples resided in seasonal and semi-permanent encampments within the region’s mountainous areas, near springs or along the shores of the large Pleistocene lakes dotting the valley floor. These bodies of water eventually receded as the Ice Age drew to an end, revealing the expansive playas that dominate this wedge of the Mojave Desert, including Rogers Dry Lake, home to Edwards Air Force Base.

Numerous Indigenous trade routes crisscrossed the desert floor, connecting coastal area tribes to interior territories and beyond. Within the last 1,000 to 2,000 years, anthropologists have theorized that Shoshonean-speaking peoples of the Uto-Aztecan language group began moving into the area. Distinct tribal groups include the Serrano, who occupied much of Antelope Valley proper into the San Gabriel foothills; the Kitanemuk of the Tehachapi Pass region and further east; the Kawaiisu, whose territory covered the Fremont Valley into the southern Sierra Nevada; and the Tataviam, which ranged from the far western San Gabriel Mountains into Tejon Pass.

By the late nineteenth century, most of these tribal groups were displaced from their ancestral lands through the import of disease, forced removal, enslavement, massacres and other egregious acts perpetrated by Spanish colonists and successive waves of other non-Indigenous interlopers.

As the region’s native population dwindled, the physical landscape, with its unique biotic communities, was drastically and permanently altered. This upheaval was swift: pronghorns, believed to have numbered around 7,000 during the 1880s, began to vanish from overhunting, habitat degradation and competition for food and water from domesticated cattle and sheep. By the 1940s, the valley’s namesake antelope herds had disappeared for good.[2]

Swaths of native bunch and perennial grasses, providing sustenance and habitat for small and large game, birds and other fauna, faded due to excessive grazing and the spread of invasive weed species. Grizzlies and other large predators were hunted to extinction. The flourishing Joshua Tree woodlands, extending from the foothills of the San Gabriel and Tehachapi Mountains, were unapologetically uprooted and cleared for farming in Littlerock, Llano and the valley’s agricultural communities.

Once the ground was scraped and tilled, dryland farming began in earnest during the 1870s. A wet period between 1880 and 1893 allowed farmers to cultivate 60,000 acres of wheat, barley, alfalfa, fruit and nuts. When a ten-year drought occurred during the mid-1890s, farmers compensated for the lack of rainfall by aggressively pumping groundwater. Pumping peaked by 1953 when 87 percent of crops were irrigated from local groundwater sources.[3]

Like most agricultural areas of Southern and Central California, Antelope Valley’s groundwater was overdrafted by the mid-twentieth century. Then, in the 1970s, cheap water from Northern California became available via the newly completed California Aqueduct. As a result, the 45,000 acres of land under cultivation in the Antelope Valley and surrounding Mojave Desert had the highest rate of agricultural water use per acre in the state.

Today, 35,000 acres of desert land, originally cultivated within Antelope Valley, lie fallow while about 10,000 acres are still actively farmed. The unincorporated town of Littlerock, historically branded as “The Fruit Basket of the Antelope Valley,” today struggles to retain its rural character as the region’s urbanized centers expand.

By the mid-twentieth century, the defense and aerospace industries supplanted agriculture as the primary driver of the valley’s economy. Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Boeing, NASA and the military continue to be the area’s predominant employers. During the early 1980s, the region began to experience unprecedented growth, boosted by Reagan-era defense spending and spikes in greater Los Angeles home prices. Cost-conscious buyers looked toward the exurbs for more affordable options, and the Antelope Valley offered the best value due to its proximity to Los Angeles.

A building and buying frenzy in the Palmdale-Lancaster areas resulted in record growth. In 1980, the U.S. Census counted approximately 60,000 residents. The population grew to 222,000 by the mid-1990s, and to 485,000 by 2010—an eight-fold increase within thirty years.[4]

Mike Davis, in his eye-opening preface to City of Quartz (1990), aptly states:

The desert around Llano has been prepared like a virgin bride for its eventual union with the Metropolis: hundreds of square miles of vacant space engridded to accept the millions, with strange prophetic street signs marking phantom intersections like ‘250th Street and Avenue K.’

Indeed, the projected development of vast swaths of Antelope’s Valley’s “vacant” desert land is mind-boggling and can only be understood when one drives east across the empty expanse, passing the endless street signs bearing bizarrely increasing numbers.

Like all real estate booms, the Antelope Valley busted in the early 1990s as a national recession took hold. The economic downturn was exacerbated by drastic federal spending cuts at the end of the Cold War era, negatively affecting defense and aerospace contractors throughout Southern California. With so much of its economy tied to these industries, the valley was hit particularly hard. After the local economy tanked, the area’s home values plummeted—especially in the newer cookie-cutter suburbs. USA Today dubbed Palmdale “the foreclosure capital of California.” Large tracts of houses were left unfinished; squatters began to occupy empty homes and crime spiked.

One subdivision at Avenue J and 30th Street West, branded as The Legends, became infamous for its cameo in the finale of Lethal Weapon 3. After the subdivision’s investors abandoned the project, forty-eight of its Spanish-themed tract homes were left deserted. Warner Bros. realized that it would cost producers less to rent the subdivision than to construct their own set to stage the film’s explosive climactic ending. In January 1992, after Warner’s had leased the blighted tract for $25,000, the film crew set fire to twelve homes, with Mel Gibson and Danny Glover fighting their nemesis among the propane flames.[4]

Reflecting the nation’s struggles, the Antelope Valley’s boom-and-bust real estate cycle would ultimately repeat itself. During the economic recession of 2008, unemployment rose to 17.2 percent and home prices shrank to 70 percent of their original value but have since rebounded. According to Zillow, Palmdale’s median home value in late 2017 is $280,500; Lancaster’s is $252,600.

As the last affordable area for new single-family homes in Los Angeles County, the Antelope Valley has enabled many people of color to purchase property, resulting in a shifting racial demographic. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, 20.5 percent of Lancaster’s residents are African Americans, making up 14.8 percent of Palmdale’s population. More than half of Palmdale’s residents are of Hispanic or Latino origin, as is 38 percent of Lancaster.

Before the late 1970s, the population of Antelope Valley was predominantly white, although people of color were beginning to relocate here in smaller numbers. Many arrived mid-century to work for the defense, aerospace and related companies, and some wanted to escape the urban environment and escalating crime of inner-city neighborhoods. However, African Americans were not necessarily welcomed in many parts of the valley. A 1989 Los Angeles Times article quoted former school superintendent Dr. William Shaw, who stated that “Blacks couldn’t live in Palmdale…[locals] would tell you that directly to your face.” A resident of Sun Village, Shaw had moved to the valley in 1957. Indeed, African Americans were not only prevented from living in Palmdale but also in Lancaster and areas south of Avenue T.[5]

Sun Village is an unincorporated rural community near 90th Street and Palmdale Boulevard, historically considered the Antelope Valley’s first African American enclave. It was founded in 1938 when Melvin Ray Grubbs, an African American lawyer from Chicago, partnered with the Marbles, a local white family, to develop 1,000 acres of desert land for home sites.

The new company offered financing that enabled Black families to purchase property in the valley, with no threat of “redlining” or other discriminatory real estate practices. The place seemed downright desolate to newcomers from Los Angeles, especially since most homes lacked electricity and other essential utilities. For those who persisted, Sun Village became a much-loved community.

During the 1960s, Sun Village had nearly 2,000 residents and boasted a vibrant downtown scene with shops, restaurants, churches, nightclubs and other Black-owned businesses. A public park was named after baseball legend Jackie Robinson, who attended its dedication in 1965. Frank Zappa, who spent his teens in nearby Lancaster, wrote and released “Village of the Sun” on his 1974 album Roxy and Elsewhere.[6] He sang about Sun Village’s brutal sandstorms and outlying turkey farms while calling out friends from the community he remembered so fondly.

Goin’ back home

To the Village of the Sun

Out in back of Palmdale

Where the turkey farmers run

I done made up my mind

And I know I’m gonna go to Sun Village

Good God I hope the wind don’t blow

African Americans are no longer the majority of Sun Village’s 12,000 or so residents. However, the City of Palmdale is now considered more racially diverse than the rest of Los Angeles County, with white and non-white populations nearly equal in number.[7] The shift occurred during the 1990s when a new wave of African Americans, Latino and other non-whites relocated to the Antelope Valley, seeking to move up the economic ladder or simply raise their families in a safer community with better schools. This influx further shifted the area’s existing white hegemony and racial makeup.

The transition has not been an easy one. Documented pockets of white supremacist activity, neo-Nazi gangs, and other forms of racism have festered in the Antelope Valley for decades. Meanwhile, white residents have accused newcomers of bringing crime and urban gang culture with them. A quickly growing population combined with periods of economic instability stoked gang violence and hate crimes.

In 1997, Lancaster’s racial strife hit the national stage when The New Yorker published William Finnegan’s investigative excerpt “The Unwanted.” Finnegan’s controversial story chronicled the lives of teenagers involved in neo-Nazi and skinhead gangs of the Antelope Valley during the mid-1990s. His essay provided a chilling and intimate account of his embedded experience, culminating in a gang member’s murder by an opposing gang affiliate at a party. He states the following in his essay:

Juvenile crime is a major problem [in Antelope Valley], usually attributed to “unsupervised children”—to, that is, the huge number of kids whose parents can’t afford after-school care and often don’t return from their epic commutes until long after dark.

Finnegan suggests that the valley’s gang violence resulted in part from the region’s meteoric growth, which overwhelmed community services such as public schools in his analysis of this complex issue. Moreover, for the many parents required to make grueling daily commutes, there were few, if any, quality or affordable alternatives to leaving their children unsupervised, forcing them to effectively raise themselves. In addition, Finnegan pointed out that, for the most part, people of color who purchased homes were upwardly mobile. In contrast, he suggested that much of the white population living among them were economically stagnant or struggling.

A decade after The New Yorker story came out, Lancaster voters chose R. Rex Parris for mayor in 2008. Parris, a Republican, is now serving his fourth term. Before entering public office, he headed a personal injury law firm. Billboard advertisements for the firm are scattered across the valley.

Parris’ governing style is considered controversial. For instance, in 2009, he supported an ordinance banning pit bulls in city limits—seen by many as an anti-gang measure. Then, he cracked down on residents relying on Section 8 federal housing vouchers and personally contributed funds to a program that provides the homeless with one-way bus tickets out of Lancaster. Later, he circulated a campaign mailer insinuating falsely that an African American man running for city council was a “gang candidate.” Finally, to help a financially floundering local hospital, Parris actively promoted “birthing tourism,” for which wealthy Chinese people paid a fee to bear their babies as U.S. citizens while on tourist visas. A local newspaper poll showed that 95 percent of Antelope Valley residents opposed the idea, so the plan was scrapped. Understandably, Parris’s polarized constituents either love him or hate him.

In contrast, the mayor and his team have been credited with revitalizing the city’s downtown district along Lancaster Boulevard, home to MOAH (Museum of Art and History). In addition, he enticed BYD, China’s largest manufacturer of electric vehicles, to open a factory in Lancaster. But what Parris is perhaps most known for is his relentless push for Lancaster to be the nation’s first Zero Net City and the “Alternative Energy Capital of the World.”

A 2013 New York Times article quoted him as stating, “I may be a Republican. I’m not an idiot.” To provide Lancaster with its renewable energy infrastructure, city leaders created their own municipal utility and installed photovoltaic panels for nearly all of its public buildings and schools. That same year, the city council voted for changes to the zoning code, requiring all new homes to have solar energy systems.[8]

With this progressive rooftop solar program, Lancaster has championed massive solar renewable energy projects within its western outlying areas. These include the 266-megawatt Antelope Valley Solar Ranch One, which covers 2,300 acres of previously disturbed private land, producing enough energy to power 75,000 homes.[9] Just north of the county line lies the 3,200-acre Solar Star project, considered the largest operational solar energy farm on the planet, producing 579 megawatts with 1.7 million solar panels—enough energy to power 255,000 homes.[10] The view from the Google aerial Landsat images of the valley floor reveals the enormous footprints of these solar farms.

Most of these renewable energy projects are sited on fallowed or unused agricultural lands west of Lancaster proper and north of Antelope Valley’s prized poppy reserve near major electrical transmission lines. Some locations include previously disturbed or irrevocably damaged areas, making good use of land that probably should have never been farmed or grazed in the first place—at least from an environmental standpoint. Indeed, many farmers have lined up to sell land to solar developers at premium prices.

With California now mandated to receive 33 percent of its power from renewable energy sources by 2020, it makes perfect sense that energy generation and distribution should occur close to major metropolitan areas where the electricity will be ultimately used. Still, massive renewable energy projects come with a cost, including well-documented environmental impacts that negatively affect humans, animals and plant life alike.

Dust abatement, either during initial construction or as ongoing site maintenance, is a huge issue for these facilities. In most cases, the easiest way to control dust at large-scale solar farms involves spreading lots of water or covering large areas with expensive gravel. In addition, photovoltaic arrays must be kept clean as dirty solar panels capture less sunlight and produce limited energy.

Fugitive dust is not only an issue for renewable energy projects—tract home developers, agriculture and even archaeological digs must contend with airborne particulates, often daily. Making matters worse are the Mojave’s exceptionally high winds, a hallmark of desert life. In the Antelope Valley alone, wind speeds may reach 25 mph and above and occasional gusts of 75 mph are not uncommon. Consequently, these frequent wind events expose something far more sinister hidden within this landscape—an unsettling irony of Antelope Valley’s affordable housing and solar boom.

Lurking within Antelope Valley’s sandy soils is a mysterious and debilitating disease called Coccidioidomycosis, or “cocci” for short, more commonly known as valley fever. Valley fever is a fungal disease endemic to Antelope Valley and three other health districts of Los Angeles County, including the San Fernando and West Valleys. Some locations in and around Antelope Valley have tested positive for the disease, including a confirmed site adjacent to housing and the California State Prison in Lancaster.[11] Cycles of rain and drought exacerbate fungal growth and correlate to the rise of valley fever cases occurring within the state.

For years, epidemiologists considered cocci primarily isolated to California’s Central Valley, where the disease has infected thousands of people, including many high-risk inmates incarcerated at several prison facilities.[12] Cocci is known to thrive in various arid and semi-arid regions of Central and South America and the American Southwest, including Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Utah and Arizona, where two-thirds of the nation’s reported cases occur each year.[13] A 2015 Mother Jones article stated that “the disease kills more Americans than West Nile, hantavirus, rabies, and Ebola combined.”

It doesn’t take much effort to liberate cocci from the soil—tilling a field, bulldozing a plot of land, or riding dirt bikes and ATVs may expose and release hidden fungal spores of Coccidiodes spp. into the surrounding air. In 2013, California State and San Luis Obispo County health officials confirmed that twenty-eight workers constructing a large-scale solar generation site near the Carrizo Plain had contracted the disease.[14]

Natural occurrences do so, too, such as an outbreak of valley fever in Ventura County that was released during the 1994 Northridge earthquake. But more often than not, some form of human activity causes the disease to spread. Once airborne, dry desert winds can carry the pestilence for miles, randomly targeting local residents and travelers alike. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control has labeled cocci a “silent epidemic,” infecting 150,000 individuals throughout the U.S. each year.

In 2016, some 714 valley fever cases were reported across the county by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. This represents a 37 percent increase in cocci-related infections from 2015—a four-fold increase since 2009.[15] The majority of Los Angeles County cases occurred in Antelope Valley, where the likelihood of catching the disease is nine times higher than in other parts of the county. In addition, many of those infected develop immunity without even knowing they’ve been exposed.

Although anyone is at risk if exposed, cocci will infect twice as many men as women. The elderly, the very young, pregnant women, those with compromised immune systems or chronic health conditions, such as diabetes, are at higher than average risk. In addition, certain racial and ethnic groups, including Pacific Islanders, Native Americans and Latinos, are more susceptible to the disease. African Americans and Filipinos appear to be disproportionately affected by the “disseminated” form of valley fever, a far more severe, life-threatening condition.[16] Those traveling within a cocci-contaminated area with no acquired immunity protection are also at risk.

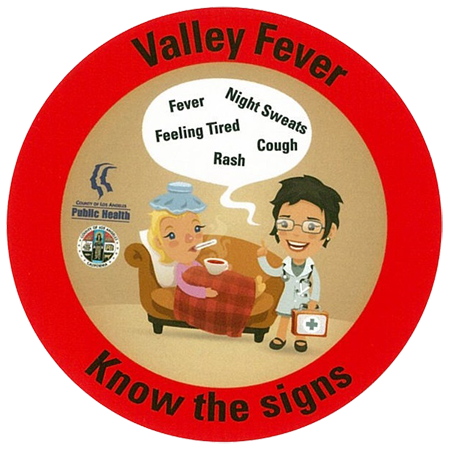

Valley fever awareness sticker from the County of Los Angeles Public Health’s website.

While 60 percent of those infected with cocci suffer either mild effects or none at all, 30 to 35 percent will develop flu-like symptoms, such as overall weakness, coughing, fever, chest pains, rashes or respiratory problems, which may persist for weeks on end. If valley fever transitions into the disseminated form, the fungal infection will enter the bloodstream via the lungs, traveling through the body attacking joints, lymph nodes, bones, skin and even the brain. These complications occur in 5 to 10 percent of those infected, resulting in a series of chronic complications that require surgical procedures and ongoing medical treatments.[17] At its worst, cocci can kill outright.

According to a 2012 paper analyzing cocci-associated fatalities in the U.S. between 1990-2008, 3,089 deaths were attributed to valley fever as the direct or underlying cause of mortality, with 1,451 deaths occurring in California.[18]

On August 12, 2012, fifteen-year-old Bre Hughes, an African-American girl from the Antelope Valley, experienced flu-like symptoms so severe that her family rushed her to the emergency room. After several misdiagnoses at other medical facilities, Children’s Hospital in Los Angeles finally pinpointed valley fever as the cause. Unfortunately, however, the diagnosis came too late. Hughes had a rare, undiagnosed blood condition which made her more susceptible to the severe form of the disease. She died on August 31, 2012.

Since 2013, Ramon Guevara, an epidemiologist at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, has facilitated researchers and the community to bring about awareness of Antelope Valley’s cocci epidemic, especially for racial groups most at risk. In 2015, Guevara and two other researchers published an independent paper showing a progressive increase of cocci-related cases in the valley from 1973 to 2011.[19]

“As the cocci epidemic continues to rise,” Guevara states, “the County of Los Angeles and the industry of Public Health, in general, has not been as active or progressive in preventing valley fever as they could be.”[20] He is one of the few experts on the disease to publicly expose the correlation between the Antelope Valley’s housing boom, solar farms and an increase of new cocci-related cases.

With the Lancaster and Palmdale metros continuing to swell and an increasing number of solar farms being built, it is fair to assume that the number of valley fever cases will continue to rise. Those most at risk for the disease include at least half, and possibly more, of the population in the region. We can be sure that the desert dust will continue to blow. What is less clear is how, or when, this invisible scourge will be addressed by those charged to do so.

The author would like to thank Ramon Guevara, Dr. Antje Lauer and Magdalene Lawrence for their assistance during the research of this dispatch. Sound design for the Sun Village track by Tim Halbur. Opening photograph: soil sampled by Dr. Antje Lauer at this residential site near Avenue J and 50th Street in Lancaster, CA, tested positive for Coccidioidomycosis. This site is adjacent to the Antelope Valley California State Prison. This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] Alternative Futures of the Antelope-Fremont Valleys, California Polytechnic University, Pomona, College of Environmental Design/Dept. of Landscape Architecture, 606 Graduate Studio (2015): 175.

[2] Sharon Moeser, “Where the Antelope Played: The Life and Times of the Antelope Valley’s Namesake,” Los Angeles Times, June 11, 1995.

[4] Alternative Futures. 176.

[5] Allison Gatlin, “Leader, legend celebrated,” Antelope Valley Press, November 3, 2017.

[6] “Village of the Sun,” LP, Track 4 on Frank Zappa & The Mothers, Roxy & Elsewhere, Discreet, 1974.

[7] Alternative Futures. 178.

[8] The ordinance was updated in 2017, requiring new homes to produce 2 watts of energy per square foot, or pay mitigation fees of $1.40 per square foot to be eligible for a 50 percent discount on the owner’s energy bill, or a combination of both. Additionally, Parris’s team streamlined the once cumbersome permit process for installation and inspection of small business and residential photovoltaic systems.

[9] Wikipedia. “Antelope Valley Solar Ranch.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antelope_Valley_Solar_Ranch.

[10] “Major construction starts on Solar Projects,” Antelope Valley Times, April 27, 2013.

[11] For more on this topic, visit Dr. Antje Lauer’s website at https://sites.google.com/site/csubantjelauer.

[12] Inmates at Lancaster’s California State Prison located just east of several large-scale solar farms have been diagnosed with valley fever, and several sites around the prison tested positive for cocci. A KB Home development near the prison had several documented cases of valley fever. Source: Dana Goodyear, “Death Dust,” The New Yorker, January 20, 2014.

[13] The pathogen is endemic in many soils in the Southwestern U.S., Mexico and parts of South America. Fisher et al., “Coccidioides, Niches and Habitat Parameters in the Southwestern United States—A Matter of Scale,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 1111 (2007): 47-72.

[14] Julie Cart, “28 solar workers sickened by valley fever in San Luis Obispo County,” Los Angeles Times, May 1, 2013.

[15] “Public Health reports increase in Valley Fever Cases in LA County,” County of Los Angeles Public Health news release, July 21, 2017.

[16] Jennifer Y. Huang, Benjamin Bristow, Shira Shafir, Frank Sorvillo, “Coccidioidomycosis-associated Deaths, United States, 1990–2008,” EID Journal, Vol. 18, No. 11 (November 2012): 1723-1728. DOI: 10.3201/eid1811.120752.

[17] Some individuals develop arthritis-like symptoms (Valley fever has also been called desert rheumatism in the past). When these patients are treated with steroids, which lower the immune function, the disease can easily disseminate. Email correspondence with the author and Dr. Antje Lauer on November 6, 2017.

[18] Huang et al., “Coccidioidomycosis-associated Deaths.”

[19] Ramon E. Guevara, Tasneem Motala, Dawn Terashita, “The Changing Epidemiology of Coccidioidomycosis in Los Angeles (LA) County, California, 1973–2011,” PLoS ONE 10(8): e0136753 (August 27, 2015). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136753.

[20] Ramon Guevara, email correspondence with the author, November 1, 2017.