British architectural historian/critic Reyner Banham (1922-88) had a thing about the desert—specifically deserts of the American Southwest and in particular, the Mojave Desert. As a self-confessed “desert freak,” he dedicated a book on the subject: Scenes in America Deserta. Its title is a play on Travels in Arabia Deserta, penned by Charles M. Doughty (1843-1926), another British desert fanatic, albeit of a different continent and century. Doughty’s memoir had inspired Seven Pillars of Wisdom by none other than seasoned traveler and author Colonel T.E. Lawrence.

Banham spent twelve years exploring these arid environs and probably would have continued to do so if not for his untimely death, from cancer, in 1988. He first traveled to the U.S. in 1961 (at age 39) and did so regularly before accepting a teaching position at State University at Buffalo in 1976 (after having previously taught at University College in London from 1964-1976). By 1980, he was lecturing as a professor of art history at the University of California, Santa Cruz. During his tenure in the U.S., he traveled extensively and wrote about his experience in a variety of articles, essays and books, most notably Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (1960) and his 1971 book Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies—an optimistic celebration of the eclectic and often inharmoniously designed cityscape of angels, organized into four primary typologies: Surfurbia, Foothills, The Plains of Id, and Autopia.

His engaging and accessible style of writing on contemporary architecture, built environments and varied human activities brought him celebrity and acceptance by the masses with the 1972 BBC production of Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles, where he takes the audience on a humorous car tour of L.A. while riding in a female-voiced, gas-guzzler known as Baede Kar, a tribute to Karl Baedeker, a nineteenth-century German publisher of popular guidebooks for tourists. The tour travels to the Watts Towers, the Venice canals, and at one point meets up with artist Ed Ruscha for a bite at a popular Sunset Strip drive-in.

Like J.B. Jackson, Banham was equally transfixed with the vernacular of built environments he encountered on a daily basis as he was with more formally accepted forms of high modernism. He was a connoisseur of both high and low architectural design, pop culture, art history and technology, with his texts melding these themes seamlessly together. His writing combined personal narrative and witty observation along with more scholarly research in an accessible, entertaining and informative mix that continues to resonate with students and practitioners of architecture and civic planning today.

Banham was first introduced to the Mojave Desert while speeding across it on Interstate 15, like so many travelers passing through this desert on their way to or from Las Vegas or Los Angeles. At some point, the urge to pull over for a bathroom break or perhaps boredom drove him to stop and explore Rasor Ranch Road. Forsaking the air-conditioned comfort of his vehicle, he and his traveling companion decided to take a closer look at the surrounding landscape. The two ended up briefly exploring the area near the Mojave’s geographical center at Baker, California, which is home to the world’s tallest thermometer at the now-defunct local eatery Bun Boy.

This particular outing led him to undertake subsequent desert road trips that, in turn, inspired him to embark on his full-book-length meditation of the American Southwest, Scenes in America Deserta. At the start of the book, Banham details the utilitarian railroad architecture of the Spanish Colonial-styled Kelso Depot, built by Union Pacific in 1923, which had formally served as a passenger train stopover and now located in the heart of the Mojave National Preserve.[1] Acutely aware that his perceptions of the American Southwest were colored by British desert authors that he admired (revealed in the book’s second chapter while discussing Kelso Depot), Banham finds it difficult not to reference the depot as a “rainswept township in the Scottish border country.” I wonder how Banham, who had initially referred to Kelso as “someone else’s private oasis,” would respond to its restored use as a visitor center for the Mojave National Preserve and, on occasion, an art gallery.

Banham was quick to compare and differentiate between rail and road desert travel; indeed, he stated how in the Mojave “the railroad lurks in its crevices, [whereas] the freeway hops from ridge to ridge,” yielding a superior vantage point that “opens enormous views” exposing the “immensity of the terrain” that only travel via car can offer because the driver must be (hopefully) aware and mindful of her movement through the landscape. In the fifth chapter, Awheel in the Waste, he elucidates:

An American desert may be cynically described as an arid zone with a four-lane highway slapped down in the middle of it. That is, nowadays, the way in which American deserts are usually seen—that legendary, hallucinating view through the windshield of an endless ribbon of blacktop or smeared concrete being devoured somewhere under the front of the car and—in the rear view mirror—being discharged out back. And that view will normally be seen by Americans with no great interest in deserts; they will be awheel on Interstate 40 or whatever because they are going somewhere else—usually Los Angeles.

Throughout the book, Banham visits and comments on other stunning Southwestern locations such as Wyoming’s famed Red Desert, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West, Paolo Soleri’s Arcosanti and Taos Pueblo, to name a few. He discusses the work of other desert authors of note, including John C. Van Dyke, who penned the still-popular The Desert in 1901. Banham precisely characterizes Van Dyke’s writing as “painfully intense, sometimes affectedly ornate in an Art Nouveau kind of way—what I seem to hear echoed from time to time in overwrought patches of Ray Bradbury and practically every caption writer in color supplement features about the Southwest.” However, he also goes on to admirably state, “In the eighty years since it was first published, The Desert has been a success, a legend, and unread masterpiece, a treasure, a cult book… .” For Edward Abbey, a contemporary author of Banham’s, it seems he has less use. Banham appears irritated with Abbey’s antisocial protestations and his deep ecology bent.

Banham had a particular affinity for the Mojave Desert landscape south of Shoshone and north of Baker, which can be driven via California State Route 127. This area, just southeast of Death Valley, is called Silurian Valley. Later in the book Banham describes the lay of this land, from its off-roading culture recreating in the sandhills of the Dumont Dunes to the spectacular scenery of the drive:

Much as I love Death Valley, however, I have always preferred the territory to its south, that long and fascinating drive through Shoshone and then through nothing much at all for forty-five miles south of the county line to Baker. Yet that forty-odd miles of nothing much includes some scenery, mountainous and otherwise, in detail and at large, which is truly magnificent. It is a region dominated by salt and chemical, sand and rock, and sun. Even the ever tenacious creosote bush holds on with difficulty in much of this land, and at one point sand, pure windblown sand, makes a rare appearance as a builder of mountains.

Continuing with a particularly engaging passage, he describes the exhilarating experience of riding his bicycle across Silurian’s hardpan playa. An avid cyclist, he was known to bike to work on campus most days:

Given a really hard, smooth soda surface like that of Silurian Lake, north of Baker, which is almost glassy and without crackle patterns over much of its area, one can move with a completeness of freedom a cyclist cannot enjoy anywhere else. Swinging in wider and wider circles or going head down for the ever-retreating horizon, the salt whispers under one’s wheels and nothing else is heard at all but those minute mechanical noises of the bike that are normally drowned out by traffic. Swooping and sprinting like a skater over the surface of Silurian Lake, I came near as ever to a whole-body experience equivalent to the visual intoxication of sheer space that one enjoys in America Deserta.

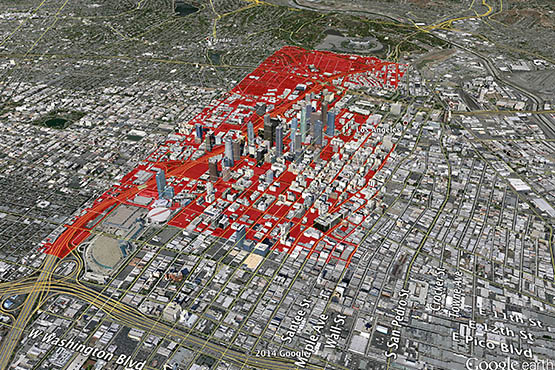

Overlay of Aurora Solar (Iberdrola, LLC) 2.45 square mile proposed industrial solar project on top of downtown Los Angeles. Image courtesy of Mojave Desert Blog.

In consideration of Banham’s keen observations, I wonder how he would respond to the proposed use of the Silurian Valley as the site of a 200-megawatt industrial solar facility on 1,572 acres or 2.45 square miles, built by Aurora Solar, a subsidiary of Spain’s Iberdrola, LLC? To get a picture of how vast a 2.45-square-mile solar field actually is, take a look at the imposition of the proposed development onto Downtown Los Angeles to visually grasp the immense footprint of this “green” project. On a positive note, the federal government gave the “thumbs down” to Iberdrola’s proposal in late 2015.

For Banham, the Mojave was the archetype of all American deserts. “[It] is my baseline desert, my first instance and last resort,” he states.

My instant response to the word desert in a flashcard test will always be a gravelly plain with creosote bushes, and jeep tracks leading up to a bony hill, varnished brown in the distance, and a double thunderclap out of the upper air as a plane from Edwards Air Force Base cracks through the sonic barrier.

Banham stressed that he loved the Mojave not because it simply offered isolation and respite from other humans and their activities, but because it revealed to him “more traces of man to be seen, traces more various in their history and their import.” A landscape devoid of human presence and activity was not what he yearned for; one that mirrored the triumphs, as well as the follies of humankind, was what delighted him the most.

The desert is also seen as an appropriate place for fantasies…of dune buggy maniacs and lone hikers, the seekers after legendary gold mines, the exploders of the first atomic devices, the proponents of advanced missile systems, and diggers of gigantic earth sculptures. Never forget that it was in the Mojave that the first claimed UFO sightings took place, and the pioneer conversations with little green men from Venus. In a landscape where nothing officially exists (otherwise it would not be “desert”), absolutely anything becomes thinkable, and may consequently happen.

All quotes from Reyner Banham, Scenes in America Deserta (Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith Books, 1982). Photo of Reyner Banham cycling on Silurian Dry Lake by permission of Tim Street-Porter. © Tim Street-Porter 1981-2014. All rights reserved. This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.