In California, African Americans were not allowed to homestead before 1900 due to exclusionary state laws requiring applicants to be white citizens.[1] At the onset of the twentieth century, these racist laws were somewhat relaxed. As a result, agricultural settlements began to prosper in Fresno, San Bernardino, Tulare and Yolo counties with African Americans who had already migrated to California, thus challenging the concept of having arrived at the frontier in wagon trains. The oldest in the state is believed to be in Guinda, California, near Sacramento. Guinda was considered “a refuge for freed slaves,” attracting at least fifty African Americans to relocate at the turn of the century. Some acquired substantial land holdings, such as former slave Basil Campbell, by the time of his death in 1906, owned 5,000 acres of land.[2] Tulare County’s Allensworth was not a homestead community but a town developed by African Americans to achieve self-governance. Now a state park, Allensworth, is perhaps the most famous African American intentional agricultural settlement in California.

Annie Taylor of Missouri (1888 – unknown). © Dr. Barbara Gothard 2022.

A few years later, at least two African American homesteading communities formed in San Bernardino County between 1900 and 1910, including one solicited by The Forum, a Los Angeles-based African American civic club. Through the Forum’s 1903 promotional effort, Black families began homesteading desert land in the arid Sidewinder Valley near Victorville, California. Sidewinder Valley’s first homesteader worked 640 acres using groundwater for irrigation, but the supply was insufficient to support the burgeoning community. How many families relocated to Sidewinder Valley from greater Los Angeles is unknown. However, a 1914 newspaper account reported that Blacks had homesteaded more than 20,000 acres of desert land here.[3] If each of these families had leased 640 acres, up to thirty families may have homesteaded within the valley. Over the Cajon Pass, The African Society, based in San Bernardino proper, raised $10,000 in capital for African Americans to colonize Southern California’s Inland Empire.[4] The Black-owned Murray’s Dude Ranch, located on forty acres in Apple Valley, operated as a guest ranch and movie set from the 1920s into the 1960s.

In The Mojave Project Reader Volume I dispatch, “Experiments in Desert Utopic Living,” Kim Stringfellow notes that “…as white families were moving to the racially exclusive Llano del Rio colony, around two dozen African American families were heading out from Long Beach, Whittier and Los Angeles to homestead deep within the eastern Mojave in Lanfair Valley at a site named Dunbar, now part of the Mojave National Preserve.” The valley, located in the eastern Mojave Desert near the California and Nevada state lines, is situated between the Castle Mountains and Piute Range to the east, New York, Mid Hills, Providence mountains to the west, and Vontrigger Hills to the south. The area is a high desert Joshua tree woodland, typically hot and arid.

The story of this early twentieth-century African American homestead settlement at Lanfair/Dunbar was not widely known or reported until recent years. Dennis Casebier, the “pioneer researcher” and late founder of the Mojave Desert Heritage & Cultural Association, discovered their history while researching the Mojave Desert in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Casebier, introduced to the area as a Marine stationed at Twentynine Palms, pursued Mojave research at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and documented numerous oral histories of the eighty-three homesteaders in the area. During these interviews, Casebier discovered that African Americans homesteaded twenty-three tracts in the Lanfair/Dunbar community—seven of which were women—and began his more extensive research about the African American homesteaders who settled in the Mojave between 1910 and 1930, chronicling his comprehensive fact-finding results and oral histories.

This previously untold story of the Lanfair/Dunbar African American homesteaders attracted the attention of the Mojave National Preserve National Park Service’s chief archaeologist, David R. Nichols. As part of the National Park Service Cultural Anthropology program and Obama-era Civil Rights Initiatives, Nichols commissioned researchers Rebecca Austin and Ginny Bengston to conduct an anthropological and ethnological study designed to “…remedy perceptions about homesteading in general, westward migration, and the stories of post-emancipation life for African Americans.” Their study utilized an ethnohistoric approach, confirming that “Lanfair was not a myth.”[5]

William H. Carter of Annie Taylor of Virginia (1844 – 1926). © Dr. Barbara Gothard 2022.

The Lanfair/Dunbar colony began when the Eldorado Gold Star Mining Company’s African American owners placed an advertisement in the Los Angeles Herald on May 5, 1910, seeking “Colored Men to become homesteaders” in Lanfair Valley. The mine’s owners and the homestead applicants did not fit the usual homesteading stereotype of poor white nuclear families. These were African Americans willing to trade the comforts of more urban settings for what proved to be the harshness of the desert to overcome “…challenges of interracial romance, create generational wealth and land ownership.”[6] Twenty-three of the families who responded to the advertisement became homesteaders in Lanfair Valley and formed the town of Dunbar. They maintained a relaxed relationship with their fellow homesteaders, who recognized they needed each other to survive. There was only one school that all Lanfair Valley children attended.[7]

In 1910, when these African Americans began moving to the area, the American Southwest was experiencing an exceptionally wet climate. There was ample rainfall for non-irrigated farming, estimated to be about ten inches of rain per year. Although Lanfair Valley receives more precipitation than much of the Mojave Desert, eight to ten inches is highly unusual. As years went by, these uncommon rain events began to decrease steadily. Utilizing the valley’s groundwater was difficult and economically impractical for the Lanfair farming community—the water was brackish, requiring landowners to drill down 360 feet to reach water safe for drinking and cooking. In addition, Lanfair Valley ranchers, who had developed groundwater sources for watering their stock, refused to share water with the valley’s farmers. With restricted access to water in the arid Mojave Desert, the homesteaders had to rely solely on rain for their crops, but eventually, the rain did not come.

Complicating their farming efforts was the soil’s poor quality resulting from sandy washouts and geological rock debris reigning down from the mountains. The harshness of the desert terrain and severe drought would drive the homesteaders away from Lanfair/Dunbar when the rains petered out by the 1930s. Some descendants of these African American homesteading families continue to live in the Bullhead City/Laughlin area.

Understanding the past pays tribute to the lives and contributions of our African American ancestors in California. Their stories help inform how we can better deal with lingering injustices today, learn from their persistence and resilience, and appreciate how the value of knowing about them enriches our lives.

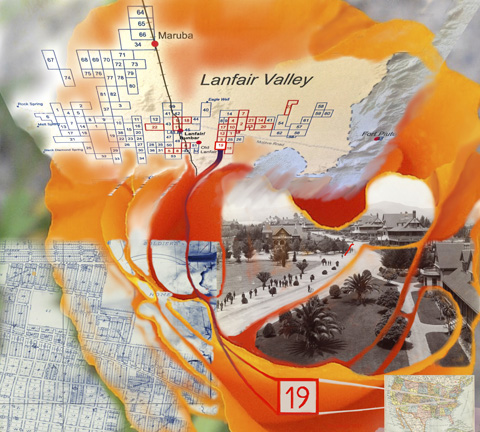

The installation view of Gothard’s 2022 exhibition at the San Bernardino County Museum included twenty-three digital paintings on raw linen canvas and a floor graphic of the Lanfair Valley homestead tract map. In addition, a first-of-its-kind story map showing the migratory journeys of the homesteaders created by ESRI staff was accessible to museum visitors.

Author’s note: The importance of illuminating the stories of these specific African American homesteaders to California’s history cannot be understated. Through my research-based Art + Humanities multimedia installation Contradictions – Bringing The Past Forward© I visually interpret the previously untold stories of these homesteaders through a framework of change, continuity, diversity, interconnectedness, community, identity and belonging. Contradictions – Bringing The Past Forward is a guided visual interpretation of 100-year-old stories about the impact of the Mojave Desert on their lives. Contradictions is, to my knowledge, the first contemporary Art + Humanities installation focused on the Lanfair/Dunbar African American homesteaders.

Contradictions – Bringing the Past Forward© by Dr. Barbara Gothard is on exhibition through August 10, 2022, at the Victor Valley Museum, 11873 Apple Valley Road, Apple Valley, California. The museum is open Wednesdays through Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Access the online ESRI interactive story map for Contradictions to view additional artwork.

This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.