It was an idyllic era for us ‘old-timers.’ We climbed the obvious lines, picked our competition and leisurely experimented with techniques and equipment. Standards rose slowly and we had a hell of a lot of fun. —John Wolfe

Waiting for the sun to dip behind the distant reaches of Mount San Gorgonio, they wait and whisper, watching colors crescendo and light the edges of the rocks, framing what could almost become a stairway along the skyline.

Every day in the park, the sunset seems to beckon those present to pause and take notice of the changing light. From every corner and crevice around Intersection Rock, the Old Woman, Cyclops and the Blob, tiny figures appear above the horizon, find a perch, and turn to gaze west. Hundreds of brown, orange, tannish pink and speckled white quartz monzonite formations fill the landscape in every direction.

The shadows cast in the evening light turn the weathered pockets and oxidized faces slightly purple and dissolve some of the rougher texture into a diffused light, giving the illusion of a soft, rounded body—the belly of the earth slowly revealed through hundreds of thousands of years of erosion by wind and water.

Looking down at the road and adjacent parking lot, Dan explains to Sierra how the road was moved; how it used to pass around the east side of Intersection Rock when there was no parking lot. Dan spent countless nights camping in Hidden Valley as a teenager, learning to climb and immersing himself in the Monument’s landscape and its fledgling climbing community. According to Zacks:

All of a sudden I saw like thirty-five years of my footprints in Hidden Valley, thousands of them, all glowing on the ground. It was like they were all there. I have walked around this place a lot in my lifetime. I have that relationship with this park—a history with almost everywhere in the park I go.

Almost every rock formation in Joshua Tree National Park has a name and a place in human history. The vast 800,000 acres that comprise Joshua Tree National Park today house historical sites up to 5,000 years old where Native American groups, including the Pinto Man, Chemehuevi, Serrano and Cahuilla people, sought winter shelter in the warm coves of rocks near the occasional oasis, while tracking small mammals and deer for food and gathering mesquite beans, chia seeds and various root crops. Rock art can be found in caves and on exposed rock walls in and around the park. Much later, commercially worked deposits of gold altered the landscape and man’s relationship with this place, and boarded-up mines can be seen to this day in and around the park.

About a decade after it was established as a National Monument, in 1936, Joshua Tree began drawing the attention of another kind of prospector, seeking a different kind of relationship with the landscape: The Climber.

The first recognized climbers in Joshua Tree belonged to the Sierra Club’s Rock Climbing Section (RCS). The RCS organized trips for the Sierra Club and the Boy Scouts beginning in the 1940s. For the most part, however, the community was small, with groups of friends casually meeting after school or on weekends to climb at the nearest Southern California crags and bouldering areas, such as Stoney Point, Big Rock, Mount Rubidoux, Tahquitz, Suicide Rocks at Idyllwild and Joshua Tree. Beginning in the 1950s, many of the better-known pioneers of climbing and mountaineering, including Royal Robbins, Yvon Choinard, T.M Herbert, Mark Powell and Eric Beck, also began making frequent climbing excursions to Joshua Tree.

For those early climbers, Joshua Tree offered a challenging and picturesque area to climb but it also offered a path towards self-exploration and a connection to the landscape. Ultimately, the path they forged would encourage multiple generations of climbers to test themselves here while exploring the region’s vertical geological expanses. These are the stories of climbers who traveled here to learn the language of the rocks and share a common passion for this particular landscape.

Dan Zacks’ first visit to Joshua Tree was in 1976. At age 16, Dan felt uncomfortable and confined by public education along with the artificiality of his urban surroundings. He sought time outside while sleeping in the desert under the stars to reflect on his future. Carrying a few gallons of water and some consciousness-expanding books, including those of Carlos Castaneda, Dan set out to camp for a few nights in Joshua Tree National Monument beyond the end of what is now known as Lost Horse Road. Here, he found that he could effortlessly commune with nature. His anxiety lifted and his mind settled.

On one of his last days out, Dan was approached by a man who was camping with his family. Soon after they began chatting, the man suggested Dan should be his belayer or climbing partner. This was John Wolfe, a firefighter from Mission Viejo who had been camping and climbing in Joshua Tree since the early 1960s. John, his brothers Rich and Mike Wolfe, Al Ruiz, Howard Weamer, Bill Briggs, Dick Webster, and Woody Stark would establish over two dozen of the classic climbs on Intersection Rock and other significant formations in and around Hidden Valley Campground.[1]

John and his friends eventually “incorporated” the crew as “Desert Rats, Uninhibited.” The group irreverently described themselves as “a disorganized non-organization dedicated to the principles of total and absolute unusualism.” Self-branding of this type was not unique to the Joshua Tree climbing scene. Across the U.S., inventive collectives such as the Vulgarians at The Gunks (Shawangunk Mountains, New York) paved the way in the late 1950s by climbing difficult routes, sometimes in the nude.

John and his friends eventually “incorporated” the crew as “Desert Rats, Uninhibited.” The group irreverently described themselves as “a disorganized non-organization dedicated to the principles of total and absolute unusualism.” Self-branding of this type was not unique to the Joshua Tree climbing scene. Across the U.S., inventive collectives such as the Vulgarians at The Gunks (Shawangunk Mountains, New York) paved the way in the late 1950s by climbing difficult routes, sometimes in the nude.

Despite the description, the Desert Rats were actually one of the more conservative climbing groups in Joshua Tree during this time. Although irreverent, John had strict rules for those who climbed with him. He coached Dan on how to climb every style of 5.7—face, off-width, chimney, thin crack, mixed—before going on to climb those same styles at 5.8.[2] Dan explains, “Climbing with the Desert Rats was really regimented and John’s ethics were severe—everything had a consequence.”

Considering that technical rock-climbing ability and gear were still relatively primitive, skilled climbing partners were often the greatest asset for safety and also provided the necessary encouragement to push perceived mental limitations and aim for feats that seemed physically impossible. The “partnership of rope” offered a kind of familial tribalism while assuring that certain rules and ethics would be strictly followed to provide safety while climbing.

Throughout the 1960s, climbing standards and techniques remained relatively conservative, with aid climbing—the placement of climbing gear in the rock used to pull one’s body upward—being a common form of ascent.[3] Climbers relied on a few pieces of commercially made gear available at the time, but many would design and construct their own gear, including swami belts, the precursor to the modern climbing harness. Pitons were one of the first pieces of gear made and sold to early mountaineers. The 1970s saw an increase in the popularity of climbing and many resulting innovations and improvements in gear and safety. Most of these innovations, such as padded harnesses and spring-loaded camming devices, were created by climbers themselves. In fact, Black Diamond, Patagonia, North Face, Gramicci, Fish Products and 5.10 were founded by climbers who initially designed and fabricated gear in their garages to sell out of their cars and vans.

When the Desert Rats began detailing the area’s climbs during the late 1960s, they were continuing a tradition of naming routes and recording first ascents that would build over the next four decades. Some of the more colorful route names (then and now) in JTNP include Alice in Wonderjam (The Comic Strip), Are you Experienced? (Lost Horse), Bongledesch (Intersection Rock), Fisticuffs (Tumbling Rainbow), Grand Theft Avocado (Steve Canyon), I Can’t Believe It’s a Girdle (Freak Brothers Domes), It (Hall of Horrors), Room to Shroom (Barker Dam area) and Toe Jam (Old Woman).[4]

In 1971, John Wolfe and Bob Dominick, with input from the Riverside Bunch, would co-author the first published area guidebook, A Climber’s Guide to Joshua Tree National Monument.[5] Zacks assembled and updated many of these guidebooks himself to cover “rent” for crashing on John’s couch when he was not sleeping in his van. The second and third editions were published into the late 1970s. These playfully wry but detailed guidebooks helped to introduce more climbers to Joshua Tree’s expanding vertical frontier, establishing the area as the perfect winter climbing destination.[6]

The 1979 edition of John Wolfe and Bob Dominick’s landmark climbing handbook.

The older routes established during the previous decade by the Desert Rats and others using aid techniques were later free-climbed by John Long and those identified with the Stonemasters. For example, North Overhang on Intersection Rock, first scaled by John Wolfe and Howard Weimer in 1969 using direct aid, was subsequently free climbed by Long at 5.9.

Free climbing as an end in itself was an ethic and a philosophy born on the walls of Tahquitz and Yosemite during the 1960s, through the pioneering efforts of Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt, Mark Powell, Frank Sacherer, Bob Kamps and others. This entailed climbing a route from the ground up without hanging or pulling on a piece of climbing gear or stepping in aid ladders. The technique required strength and prowess to reach the top, using climbing gear only as protection against a potential fall or misstep.

This shift in technique established a new era in rock-climbing culture. Limitations imposed by the use of aid gear and the time-consuming techniques were set aside, and the unlimited potential of the vertical world was cracked wide open. The energy that surged through the climbing community during this decade brought a new perspective to the walls that had been previously seen as too hard to climb without the use of aid.

Mari Gingery studied biochemistry in Los Angeles during the mid-1970s and eventually landed a university research-lab position studying bacteriophages. On weekends, she would test her physical limits on the rocks in and around Southern California, at Stoney Point, Suicide and Tahquitz Rocks and Joshua Tree.

Gingery found that the landscape of the Mojave Desert, with its distant vistas, offered her a counterbalance to the intense focus that she brought to her work: learning to climb, camping under the stars, developing meaningful bonds with other dedicated climbers and getting intimate with the vertical landscape of Southern California.

Mari fondly recalls the community of climbers in Joshua Tree during that time, which included John Bachar and John “Yabo” Yablonski, both of whom had “dropped out” to pursue climbing full-time. Yablonski and Bachar were committed to the lifestyle in their own ways: Bachar lived out of a 1960s red Volkswagen camper van; Yablonski lived out of his backpack.

This lifestyle grew out of a dedication to climbing full-time, or at least as often as possible. “Dirtbags,” at the time could live on three dollars a day and a toothbrush. For those who didn’t own cars, hitchhiking became the preferred way to get around. Off-the-grid climbers would hold down campsites at Hidden Valley Campground and carloads of friends would join them on weekends, foregoing weekday climbing to save their best energies for their forays with the weekend visitors.

Anybody who was climbing, you would know them. In the beginning, there was no territorialism—it was a friendly community. We were all hungry for the company of other climbers. —Mari Gingery

They shared campsites and huddled around fires in the protected boulder alcoves of the campground. Despite competitiveness, information about new climb routes was enthusiastically discussed around campfires. John Long, the self-appointed campground ambassador, would conduct a fireside chat with almost anyone, especially if it provided an opportunity to boast about a new route he had just free-climbed.

The loose group of friends also found time to frolic about the campsite, often to the disdain of park personnel who considered the climbers a nuisance. Photographer-climber Brian Rennie recalls how, on one occasion, park rangers threatened to arrest those responsible for hoisting a picnic table to the top of Intersection Rock, which provided a 360-degree scenic view while dining. Understandably, park rangers were none too happy with the prank, but had no proof of who actually did it. When the table was not removed from its perch, the rangers returned after a couple of weeks, this time offering a case of beer for its removal in lieu of legal action. The table eventually came down under cover of nightfall.

Evenings were a time to unwind from the day’s focused movements, with late-night bouldering sessions simply for play. Exploring the outer reaches of Hidden Valley Campground, Kevin Powell remembers how at night the group would occasionally wander into The Outback. Past the Negasaurus formation is a forgotten historic campfire ring whose charcoal residue remains. Some evenings, John Bachar would carry his saxophone out there. Each person would take turns on the Hobbit Hole, a wide-crack boulder problem located just behind the campfire, while Bachar riffed on his sax and the group improvised lyrics to the Roland Kirk song “Sugar.” These improvisations, “the benzoin drips from my wasted tips, the thin crack was mine. You can bet your life a thin crack like this would be hard to find” became a mantra during these late-night gatherings.

Mari’s close friend Lynn Hill considers the friends she made during this time of her life to be part of her extended family:

What began as a small group of friends expanded into a community of people from all walks of life. Quite a few were students majoring in esoteric fields like astrophysics, math and archeology. There were also a lot of unemployed vagabonds, and even a few whose lives hovered on the fringe of legality. But most of the climbers I knew held down an array of jobs and careers from carpenters and construction workers to doctors, lawyers, scientists, actors and shop managers. Climbing was the one passion we all shared in common. —Lynn Hill[7]

Many of these climbers were bound together by actual admittance or association to the Stonemasters, which formed during the early 1970s and initially included John Long, Ricky Accomazzo, Richard Harrison, Tobin Sorenson, Mike Graham, Gib Lewis and Robs Muir. The name itself represents and is synonymous with climbing culture in California during the 1970s.

To be identified as a Stonemaster, one had to be a master of stone, but also a master of his or her own mind. The only “official” requirement was to make a free ascent of Valhalla (a notoriously scary route) at Suicide Rocks in Idyllwild. However, those in the know stopped keeping official records after the first ten free ascents were accomplished. The Stonemasters’ philosophy grew out of storied mountaineering legends of climbers who survived the most challenging of situations. This vision—an outlook for living in the present, tested on the rock—was a state of mind free of distractions and completely dedicated to the act of climbing.

As a part of this visionary camp, Gingery knew just as well as any of them that climbing was a training method for your mind. To get past the fear that inevitably creeps in while climbing required “an imposed calm, where everything else has to drop away.” Fortunately, the minimal yet expansive landscape of Joshua Tree encourages this type of intense concentration.

The framework of rock presents a series of tiny geologic features that must be read by the climber’s eyes, hands and feet. Each crack, nub of quartz, edge or flake carries with it information the climber must interpret with their body. The rock doesn’t move for you; it is a stalwart, rooted force withstanding hundreds of thousands of years of wind-induced erosion and sun-stained exposure.

Climbers learn to speak the language of this landscape through the artful engagement of their whole mind/body while moving with and across the rocks. First, their eyes are drawn to the layout of the lines carved through the endless profusion of bouldery cliffs, then sandpapery faces and cracked slabs. Zig-zagging vertical and horizontal pathways become aesthetic lines directing them upward, while minute holds demand measured movements and closer listening.

Gingery is well known for her agility, strength and composure on the rock. Small holds requiring delicate crossover movement through exposed finishes did not hold her back from following John Bachar up some of the most difficult boulder problems established during this period of Joshua Tree’s climbing history.

The day Bachar successfully climbed Crank City—a V4 boulder problem west of Turtle Rock—Mari stunned everyone by immediately following the climb with no hesitation. Roy McClenahan, a newly integrated member of the crew, remembers the day well:

I was there that day. This happened during the last breaths of the 1970s. When Bachar topped out, he disappeared for a moment behind the summit and then just his head and shoulders reappeared and he was wearing this great big grin. Within minutes, Mari actually got the second ascent of Crank City. She was so stoked and so were the rest of us.

The group energy that accompanies such bouldering sessions contributed to a heightened sense of confidence and a variety of potential solutions. With each creative attempt and concentrated burst of energy towards the top, the next person to follow might see a new path that was impossible to see before. These ascents were accomplished by the individual but spurred on by fellow climbers gathered below, who called out reassuringly.

We didn’t care what we were called, Stonemaster or otherwise. We had a special bond—a tribal blend of camaraderie and self-reliance. We pursued adventure with a hearty minimalism. We climbers strove to abide the natural constraints of the rock and we valued on-sight climbing very highly. Our climbs required precision and boldness. —Roy McClenahan

For Gingery and many of the others, climbing provided grounding in their lives through commitment to process and internal ethics; the community bonded together by similar and consistent goals. In these moments of personal growth where friends were present to witness each other’s achievements, lifelong connections were forged among them but also with the landscape where it all took place. To those identified as Stonemasters, the label reflects the energy that was created among those particular climbers but also describes what the sport meant for everyone climbing in Joshua Tree during this legacy decade.

Climbers today continue to make pilgrimages to Joshua Tree to learn the language of the rock. The faces on the walls change, new routes are added as climbing styles evolve over time, but the early energy and camaraderie unmistakably endure. The dedication of those early climbing groups, who laid down roots in this place they so revered, continues to compel serious climbers, both past and present, to be part of this ever-evolving community.

Bernadette Regan grew up in a big family in a small Pennsylvania town. After discovering climbing during the early 2000s, she made her way out to California in 2004. Regan was looking for a place to climb full-time all year round, outside of a climbing gym. Joshua Tree turned out to be the ideal landing pad after she spent her first summer in Yosemite.

After applying for a climbing-shoe repair job in Joshua Tree, Regan found part-time employment at a popular restaurant called Crossroads Cafe, informally referred to as “the Living Room” by locals. Off-the-rock climbers would eat, drink and commune there after climbing. Rather than learning her customers’ actual names, Bernadette would refer to them by what they ordered; “Too Strong” Dave Mayville was always “Burger, no mayo—no fucking mayo.” Costumed, cross-dressing climbers sitting at the bar, chatting about a day’s adventures on the rocks were not unusual.

Regan states that her decision to stay in Joshua Tree after her first season was because of the community—not the climbing, which she initially found somewhat intimidating and quite painful. Years later, now working as the climbing ranger in Joshua Tree National Park Service, she hosts Climber Coffee, an early morning meet-up for the community that is sponsored by the National Park Service in a different sort of “Living Room”—Hidden Valley Campground.

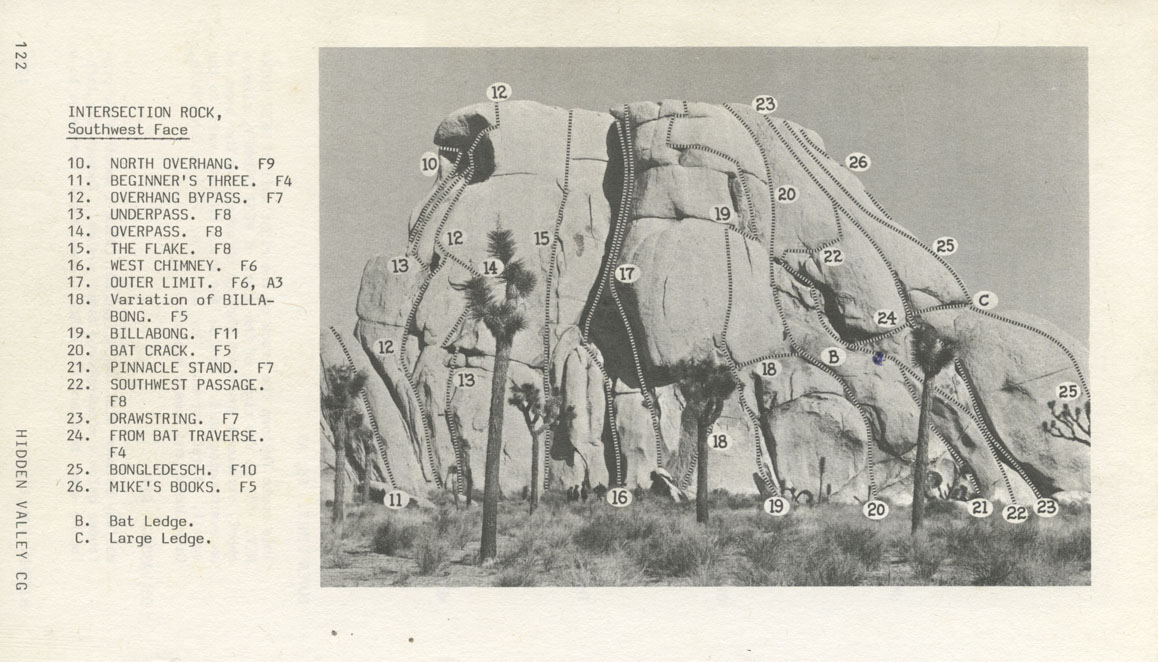

Routes for the southwest face of Intersection Rock from the 1979 edition of John Wolfe and Bob Dominick’s A Climber’s Guide to Joshua Tree National Monument.

Intersection Rock sits at the epicenter of the climbing scene in Joshua Tree National Park. To the uninitiated, it’s just the big rock next to the park’s crossroads where a day-tourist might turn right for Hidden Valley Picnic Area and the Nature Loop or left towards Hidden Valley Campground and Barker Dam. To a climber, it is home of over forty routes, many of them local classics, with each face and crack on this formation a piece of climbing history.

The parking lot on its east flank is a gathering spot for those meeting up to climb and for local guides preparing to meet families and other groups for the day’s adventures. On Saturday and Sunday mornings, during the peak season, from October to April, climbers and non-climbers gather in the campground for Climber Coffee, which has been occurring regularly for two decades. Regan moderates casual conversations for climbers about current closures, climbing conditions and other policy issues, including “Leave No Trace” practices related to recreation in the park. She remembers regular visitors by their names, but also by the mugs or containers they bring for the free coffee and tea.

These morning gatherings act as an unintimidating social and cultural bridge, where excited beginner climbers and seasoned climbers can interact and share stories. Some of the climbers are visiting for the first time. Others haven’t been back for twenty or thirty years. Those returning often comment that familiar climbing routes seem more challenging, but the place itself hasn’t changed, except that there are more visitors to the park.

For Regan, and for many of the dedicated climbers drawn to Joshua Tree, the area has become much more than a popular climbing destination. Mari Gingery and Mike Lechlinski bought land near the village of Joshua Tree during the mid-1980s. The couple is still actively connected to the local climbing community, though not as active in climbing as they once were. The friendships forged while climbing throughout California during the mid-to-late 1970s make up their extended friend and family network. Every few years they attend a reunion at the Hidden Valley Campground or at a neighbor’s house in Joshua Tree, where stories are resurrected and meals shared in the same manner as they were in past decades when everyone gathered around the campground’s picnic tables.

Todd Gordon is another climber that settled in Joshua Tree during the mid-1980s. Over time, his place became fondly known as “Gordon Ranch,” where those associated with the burgeoning dirtbag community could crash and shower if the Joshua Tree National Park campground was full—even without knowing Todd personally. However, only committed climbers were invited to stay there and an unspoken level of trust was required to do so.

The camaraderie among the climbing community is often expressed when someone is injured or dies. Climbers come together through online forums such as Mountain Project and Supertopo to offer support to those in need. Sometimes this simply entails dog-sitting for friends stuck in the hospital or joining together to raise funds through gear sales to help offset costly medical bills. Many of these local DIY fundraisers are organized at Gordon’s house. In 2009, Roy McClenahan was the beneficiary of one of these fundraisers when debilitating musculoskeletal pain had rendered him unable to work. A memorial was held at Gordon Ranch for legendary climber/stuntman Scott Cosgrove in 2016 who had suffered extensive injuries during a commercial rigging assignment less than two years earlier, at age 52. Cosgrove is credited for establishing some of Joshua Tree’s most difficult climbs including G-String (5.13d), The Cutting Edge (5.13d) and Integrity (5.14a).

Dan Zacks is now a retired emergency medical professional. In his spare time, he teaches wilderness first aid to outdoor professionals. During the late 1980s, he moved back to Joshua Tree after meeting the woman who he now fondly refers to as “his better half.” He and his wife, Cindy, a local Morongo Basin high school biology teacher, chose to raise their only daughter, Sierra, within this landscape and its caring community.

Sierra graduated in 2016 with a degree in biology from the University of California, Santa Cruz. During the summer, Sierra guides families and other adventurers through the Sierra Nevada on backpack trips lasting as long as eighteen days. Her competence as a guide is informed by a deep respect for the earth instilled in her through her parents, who themselves are encouraged and revitalized by the environmental consciousness of today’s generation.

Indeed, the Zacks are inspired by their daughter and her contemporaries’ committed desire to live more minimally and sustainably. They are impressed with how these young people spend as much time outdoors as possible—even making career choices to maximize that recreational time. They see this new generation upholding their own eco-consciousness, born out of the idealistic 1970s environmental movement that is forever at odds with corporate interests and blatant consumerism.

As a climber herself, Sierra realizes how important it was for her to be exposed to climbing culture at such an early age. She feels that her father’s friends and climbing partners unconsciously encouraged her to follow a lifestyle that she is now making her own. Akin to her father’s way of life during his early twenties, she too is living in her own converted cargo van, which she fondly dubbed “Vincent van GO” as a nod to her recent studies in art history. This pared-down mobile existence is just part of the lifestyle that allows her to live in a way that is meaningful to her.[7]

She describes her path as one of cultivating curiosity and proximity to the earth through human connection within spiritual sanctuaries like Joshua Tree—places where there is room to sit quietly and stare, get lost and find oneself again, or spend time with friends discovering one’s own place—where we can feel at home again.

Many of the climbers interviewed for this dispatch shared similar personal stories concerning the value of climbing. When you wholeheartedly pursue the discipline of climbing, you become more connected to your body, more intimate with the earth. Perhaps most significant of all, you enter into a joyful, supportive community of like-minded people. To an outside observer, climbing may appear to be about extreme physical feats and human domination of the landscape, flashy gear and branded clothing, but at the heart of the climbing community is an ethos of simplicity, stewardship, and connection to the land that continues to thrive in magical places like Joshua Tree.

This dispatch tells a portion of the rich history contained in Joshua Tree National Park. By no means does this reflect the experiences of every climber to have graced these walls. Those stories, and more, are coming. The author would like to thank the following individuals for sharing their stories and their time in support of this project: Ernesto Ale, Gary Gareths, Mari Gingery, Todd Gordon, Felipe Guarderas, Charles Hood, Markus Jolliff, Mike Lechlinski, Roddy McCalley, Roy McClenahan, John Mireles, Kevin Powell, Sabra Purdy, Bernadette Regan, Brian Rennie, Alexis Sonnenfeld, Karen Tracy, Dan Zacks, Sierra Zacks and Seth Zaharias.

Alexis Sonnenfeld, a twenty-year resident of Joshua Tree is shown climbing West Chimney, Intersection Rock in the opening photo by Kim Stringfellow. This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] Bill Briggs, Dick Webster and Woody Stark were part of a group called the Riverside Bunch, joined together by their work on the Riverside Search and Rescue team. This group started climbing in Joshua Tree around 1958. Later on, Jim Foote, Bud White and others would join the ranks.

[2] The first guidebook for Joshua Tree lists grades on a scale from F1-10 and compares this to the Yosemite Decimal System (YDS), which Royal Robbins created around 1965 after his first ascent of Open Book at Tahquitz Rock in Southern California. The YDS begins at the 5th class scale and today reaches 15.5b. Beginning with 5.10, each grade contains a sub-grade. For instance, 5.10a, 5.10b, 5.10c, and 5.10d. Before the YDS, the Sierra Club rating system was used to describe classes of climbing from 1-5, with 1 being an easy walk to 4th and 5th class, including the potential for roped sections. Aid climbing was not included in this system and, for a time, was called 6th class but now involves its own rating system for Artificial Climbing A1-5.

[3] Roy McClenahan comments: “Aid climbing wasn’t necessarily the most commonly practiced form of ascent. People have always free climbed. It’s just that whenever necessary, often in the name of expediency, aid was used. So a lot of climbs were mixed free and aid. Aid persisted on the wall climbs due to the severity of the terrain, but during the 1960s, and even more so in the 1970s, the idea of getting rid of the aid moves wherever possible, refashioning existing climbs so that they were free from bottom to top, emerged as a distinct goal. This started on the smaller climbs and somewhat contemporaneously but later spread to the big walls.” Noted from email correspondence with the author dated May 27, 2017.

[4] To date, there are over 8,000 climbing routes and over 2,000 boulder problems established in Joshua Tree National Park with more being added each week. Following the final update to A Climber’s Guide to Joshua Tree National Monument in 1980 many other guidebooks have been published with each highlighting different routes. Among them are Joshua Tree Rock Climbing Guide (Randy Vogel, 1986), Rock Climbs of Hidden Valley (Alan Bartlett, 1992), Rock Climbing Joshua Tree, 2nd Edition (Vogel, 1992, 2000), Joshua Tree Bouldering (Mari Gingery, 2000 reprint), The Trad Guide to Joshua Tree: 60 Favorite Climbs (Charlie Winger, 2004) and Joshua Tree Rock Climbs (Robert Miramontes, 2011, 2014).

[5] Rumors suggest that there was a handwritten, unpublished guidebook circulating earlier than this date.

[6] An example of Wolfe’s and Dominick’s wry writing style is expressed on page 28 in the Ethics and Equipment section of the 1979 edition, where the authors discuss unnecessary and unethical bolting: “Scarcely more supportable are six or seven bolts on WATER MOCCASIN (F5) in Indian Cove CG. Unknown climbers placed them, apparently for aid, on a route that has since been led free by a woman in moccasins. If you have a penchant for placing bolt ladders, find a nice tower in downtown Los Angeles.”

[7] Lynn Hill with Craig Child, Climbing Free: My Life in the Vertical World (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2003).

[8] Many committed climbers continue to live out of their vehicles and often refer to their cars as their cities of residence: “Where do you live these days?” “Ford, CA.”