From where I used to live, on the fringes of what had been the colony’s land, this Ozymandias was the only visible trace of human handiwork. Gleaming in the morning light or black against the enormous desert sunsets, that silo was like a Norman keep rising, against all the probabilities, from the sagebrush. —Aldous Huxley, Ozymandias, the Utopia that Failed, 1953

Llano del Rio was conceived by Job Harriman, an earnest but ambitious left-leaning lawyer who nearly became the first socialist mayor of Los Angeles, in 1911, had his bid for office not been derailed by some shady backroom dealings orchestrated in the eleventh hour of his campaign by his more well-known legal partner Clarence Darrow. Together the two were defending the radical McNamara Brothers, two union organizers charged with the infamous bombing of The Times building in 1910. Harriman—who had previously run for California governor in 1898 under the Socialist Labor Party ticket and later as a vice presidential candidate in 1900—attempted to win the mayoral race again in 1913 but was narrowly defeated in the primary election.

Disillusioned with the status quo politics of his time but determined to make good elsewhere, Harriman had an exit strategy that envisioned an economically practical socialist colony—secular, cooperative and economically self-sustainable—set geographically in the southwestern Mojave Desert where it merges into the San Gabriel Mountains. Convinced the best way to spread socialism was by way of example, Harriman and his comrades sought to build the ultimate “Socialist City” from within the brutal capitalist hegemony of his day, when “an estimated forty percent of the U.S. population had been abandoned to extreme poverty and another forty percent to conditions just a notch above.”[1] They believed when the world saw their success, other socialist communities would soon follow and for a few short years, the dream of Llano del Rio seemed attainable.

Once Harriman and his partners had secured a down payment on 10,000 acres of land valued at $80,000 from the Mescal Water and Land Company in 1913, a parcel that had been partially developed by a former temperance colony near the headwaters of Big Rock Creek, they immediately began to develop the site. Incorporated under the Llano del Rio Company, the settlement officially opened on May Day 1914 “with five families, five pigs, a team of horses, and a cow.”[2] Over 100 colonists arrived within the first year. By the next year, the population had more than doubled.

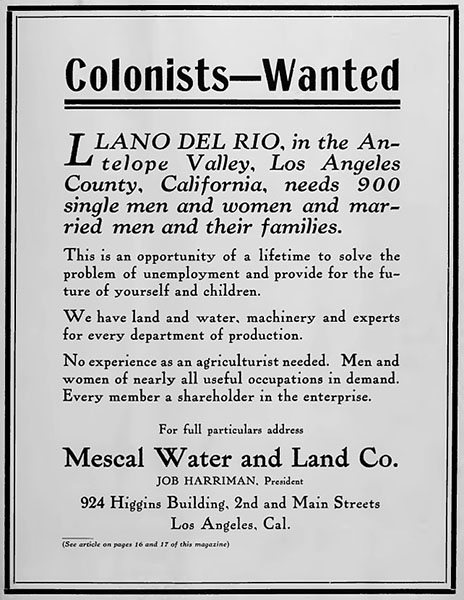

1914 LLano del Rio advertisement in The Western Comrade.

The promise of a better life with continuous employment drew hundreds to the agrarian settlement through print advertisements in national socialist journals including The Western Comrade, which Harriman and his partners had acquired in 1914. Qualifications for membership required that applicants were “idealistic, industrious, and sober” and had provided “three good references” preferably from union affiliates. One application for membership stated:

Only industrious men and women of high ideals and constructive ideas with reputations for good citizenship are desirable members of the LLANO DEL RIO CO-OPERATIVE COLONY.

The application additionally asked a variety of questions including: “Will solving the economic problem ultimately lead to solving the social problem?” and “Is happiness a state of mind or dependent upon affluent material conditions?”

Based on a social capitalist model, the Llano del Rio Company required new members to invest in the colony through a joint-stock venture—$500 cash was required upon acceptance towards a fixed 2,000 shares valued at $1 each, payable over a six-year period. Members were paid to work on-site for $4 per day with $1 going toward the purchase of outstanding stock shares. The remainder went toward collective daily expenses such as meals and lodging. Workers’ contracts stated that any future profits were to be credited to each investor’s account, a promise that never actually materialized.

As the colony quickly expanded so did its infrastructure. Irrigation ditches were laid to water acres of alfalfa, corn, vegetables, fruit orchards and livestock. Housing (both permanent and temporary to accommodate the large influx of new colonists) was built using materials produced at the on-site sawmill, quarry, limekilns and other industrial shops. In addition, a hotel, commissary and dairy along with several industrial buildings including a grain silo were constructed. The soap factory, laundry, tannery, cannery, bakery, printing press, machine shop, post office, barbershop and other trades provided employment. Children were taught at one of California’s first and largest Montessori schools. By 1917, there were over 900 colonists living at Llano and more than three-quarters of their provisions were supplied internally.[3]

“Llanoites” spent their spare time participating in a variety of cultural events including May Day celebrations, evening dances, and musical performances by two orchestras, several quartets and a ragtime band. Furthermore, a variety of extracurricular activities were accessible, such as book, dramatic, rod and gun clubs, along with team sports and competitions. Photographs of the settlement depict a happy, robust community, although it is noted that there were troubled periods when resients had only carrots to eat for weeks on end.[4]

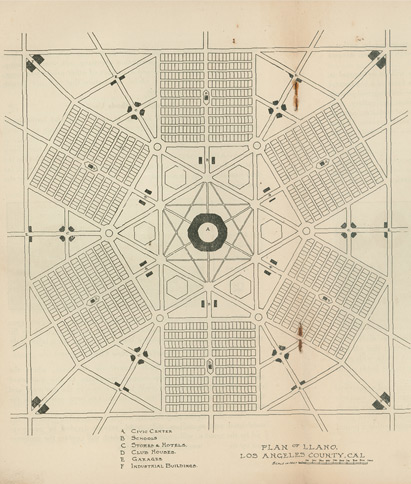

Alice Constance Austin proposed feminist design for the future “Socialist City.”

For the women involved, Llano del Rio promised a gender-neutral environment. Architect Alice Constance Austin proposed a conscious feminist design for the future Socialist City that featured a non-grid circular spatial plan with centralized communal kitchens, laundries and daycare, built-in furniture, and other modern innovations that minimized housekeeping while relying heavily on modern technologies such as electricity. Women were meant to equally participate in the everyday governance and politics of Llano. Liberating them from the daily toil of “woman’s work” was the first step in doing so.

As the domestic drudgery is taken out of the home-life, the spiritual side of the home begins to develop in greater beauty. The mother loses the character of the cook, and becomes the comrade in harness with her husband.[5]

Still, even with this idealism, the colony suffered from its share of avarice, laziness, internal bickering and factionalism. Although a general assembly of some sixty individual committees, each with its own administration and agenda was charged to handle daily affairs, a minority of Llanoites became dissatisfied with overall governance.

One group calling themselves Welfare League—more popularly known as the “Brush Gang” for their private clandestine meetings and the branch of “sagebrush” pinned to clothing to identify themselves—demanded that all decisions affecting the colony be made by popular vote rather than through the established general assembly. Eventually, Harriman expelled the group’s leaders but fringe resentment remained.

Worse were the settlement’s entangled water rights, which were challenged in court by local ranchers in 1916 and eventually lost—rendering the colony’s land holdings valueless. Outside attacks from The Times, never a friend of Harriman, continued to chip away at the settlement’s legitimacy, in turn stirring up local uneasiness and dissuading potential new recruits. At the onset of World War I scores of men left the colony to enlist or find work outside at higher wages resulting from the war.

The final blow came from one of their own. Founding Christian Socialist investor Gentry Purviance McCorkle worked behind the scenes, quietly purchasing company shares in an effort to take control of the orchard endeavor “without the socialist element.”[6] Although McCorkle’s maneuvers were eventually stopped, the fiasco had effectively bankrupted the colony by 1918. Harriman and the others relocated to rural western Louisiana, rechristening the colony as New Llano, where it thrived through the Depression years until 1938. Once abandoned, California’s Llano del Rio infrastructure was immediately sacked by its neighbors, slowly erasing traces of its fleeting socialist dream from the landscape of the southwestern Mojave Desert.

In The Western Comrade’s April 1916 issue a full-page advertisement titled “A Gateway to Freedom through Co-operative Action” states at the bottom of the call “Only Caucasians are admitted. We have had applications from Negroes, Hindus, Mongolians and Malays. The rejection of these applications are not due to race prejudice, but because it is not deemed expedient to mix the races in these communities.” Indeed, the founders may not have overtly intended to promote racial prejudice as the advertisement suggests, but offered no opportunity for people of color to join the colony. It appears from the advertisement’s wording that there were many racially diverse individuals and families who were interested in participating.

So as white families were moving to the racially exclusive Llano del Rio colony, around two dozen African American families were heading out from Long Beach, Whittier and Los Angeles to homestead deep within the eastern Mojave in Lanfair Valley at a site named Dunbar, now part of the Mojave National Preserve. These families, which included seven single women filing as heads-of-household out of the twenty-four who received patents for “proving up” their land, had come out to file 160-acre tracts or more through the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 that encouraged dryland farming. Some may have also sought to join the short-lived Harts townsite, founded by George W. Harts and Howard Folke, two African Americans who promoted their settlement as a way to bring “freedom and independence to a limited number of colored people.”[7]

From 1910 into the early 1920s, Lanfair Valley experienced a boom of sorts with at least 600 homesteading applications recorded. Some of the earliest to file were Black families—six were known to have applied in 1910, according to Dennis Casebier of the Mojave Desert Heritage and Cultural Association (MDHCA). Casebier is responsible for bringing this forgotten homesteading history to light through his extensive research, oral histories and publications documenting the history and culture of the eastern Mojave region.

Although racism in Lanfair Valley was not necessarily absent, Casebier’s oral histories with descendants of homesteaders suggest that it was downplayed for the children that had grown up attending the mixed-race Lanfair School. In one interview, Casebier’s subject reflects on whether she perceived any discrimination there. “No. They were kids to me. I didn’t care whether they were pink, red, or white.” She goes on to state, “Mr. Jones [a Black man] used to help my dad plow. And my dad helped him plow. One time, we’d gone on Saturday up to the railroad, to the post office with the team of mules, and while we were gone, a flash flood came along… Well we were stuck, and here it was evening, you know. So we stayed all night at the Joneses.’”[8]

Casebier states that despite these fond childhood memories some segregation did indeed persist, as it is known that mail sent to the area’s Black families posted to the Dunbar post office, which was located within several feet of Lanfair’s own. It is most likely that blacks did not attend local monthly dances, Fourth of July celebrations and other community events because the group that hosted them only allowed white membership—not so unusual in that day and age. Still, Casebier’s interviews with Lanfair Valley’s African American descendants state that they too were not aware of any overt racism, perhaps desiring to affirm memories to pass on to their children that erased prejudice from their families’ collective history within the eastern Mojave Desert.

In another Casebier interview, Richard Welsey Hodnett reminisced that his family’s tenure in the Lanfair Valley as a joyful period. When asked about racism, he simply commented that he was too small to remember.[9]

It rained a lot in Lanfair in those years and in the spring, as far as you could see was beautiful golden poppies all over the valley. It was beautiful, a few other different wildflowers in the mix, but the predominant flowers were golden yellow poppies… [My father] liked farming and getting all that land up there for homesteading it. He just got carried away and got excited and went up there and everyone is thrilled with that country…

These two brief forays in desert utopic living show us the potentiality for building successful intentional communities within the Mojave—if like-minded individuals have the will, stamina and subtle appreciation of the desert to participate. Within twenty years of Llano and Dunbar’s establishment, the Small Tract Act of 1938 would be passed, ushering in a modern-day desert land boom that was less concerned with socialist causes than it was with capitalist ones. Although architectural remnants of these past movements are fading fast, we can still contemplate the dreams and aspirations of these fine citizens who called the Mojave Desert home.

This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] Elisabeth Greenbaum Kasson, “Promised Land,”Los Angeles Times Magazine, May 2012.

[2] Paul Kagan, New World Utopias: A Photographic History of the Search for Community (New York: Penguin Books, 1975), 119.

[3] Francis Robert Shor, “From Socialist Colony to Socialist City: The Llano del Rio Utopian Experiment in California,” Utopianism and Radicalism in a Reforming America, 1888–1918 (Santa Barbara: Praeger, 1997), 169.

[4] Kagan, New World Utopias, 120.

[5] Shor, Utopianism and Radicalism, 173.

[6] Kasson, “Promised Land.”

[7] Dennis Casebier, “Black Homesteaders in Lanfair Valley,” Park News & Guide: Mojave National Preserve, National Park Service, 22 (Fall 2012): 1.

[8] Casebier, “Black Homesteaders,” 4.

[9] Richard Welsey Hodnett, an oral history conducted by Dennis Casebier at Mojave Desert Heritage and Cultural Association, August 18, 2000.

Photos were sourced from “Double Look at Utopia: The Llano del Rio Colony,” Aldous Huxley and Paul Kagan (authors), California Historical Quarterly, Vol. 51, No. 2 (Summer 1972), 117-154.