In the moments before the light of a thousand suns illuminated the heavens, the bellwether lifts his wooly head. Sixty-five miles to the south, in the glass-walled lounge of The Desert Inn’s Sky Room, an off-duty pit boss cradles a Bloody Mary, waiting for the show to begin. Seconds later, a Shoshone man and his son, tracking mule deer in Ely’s high country, are stopped dead in their tracks by a blinding flash of light. Several hours pass when a pregnant St. George housewife gazes out her kitchen window. Transfixed by a towering, pink-gray cloud advancing from the west, she puts her dishes down and steps outside to gain a better view. As the pastel phantasma settles, children write their names across a car window covered with fine dust that will burn their fingertips seconds later. To ease the sting, they quickly lick their fingers clean.

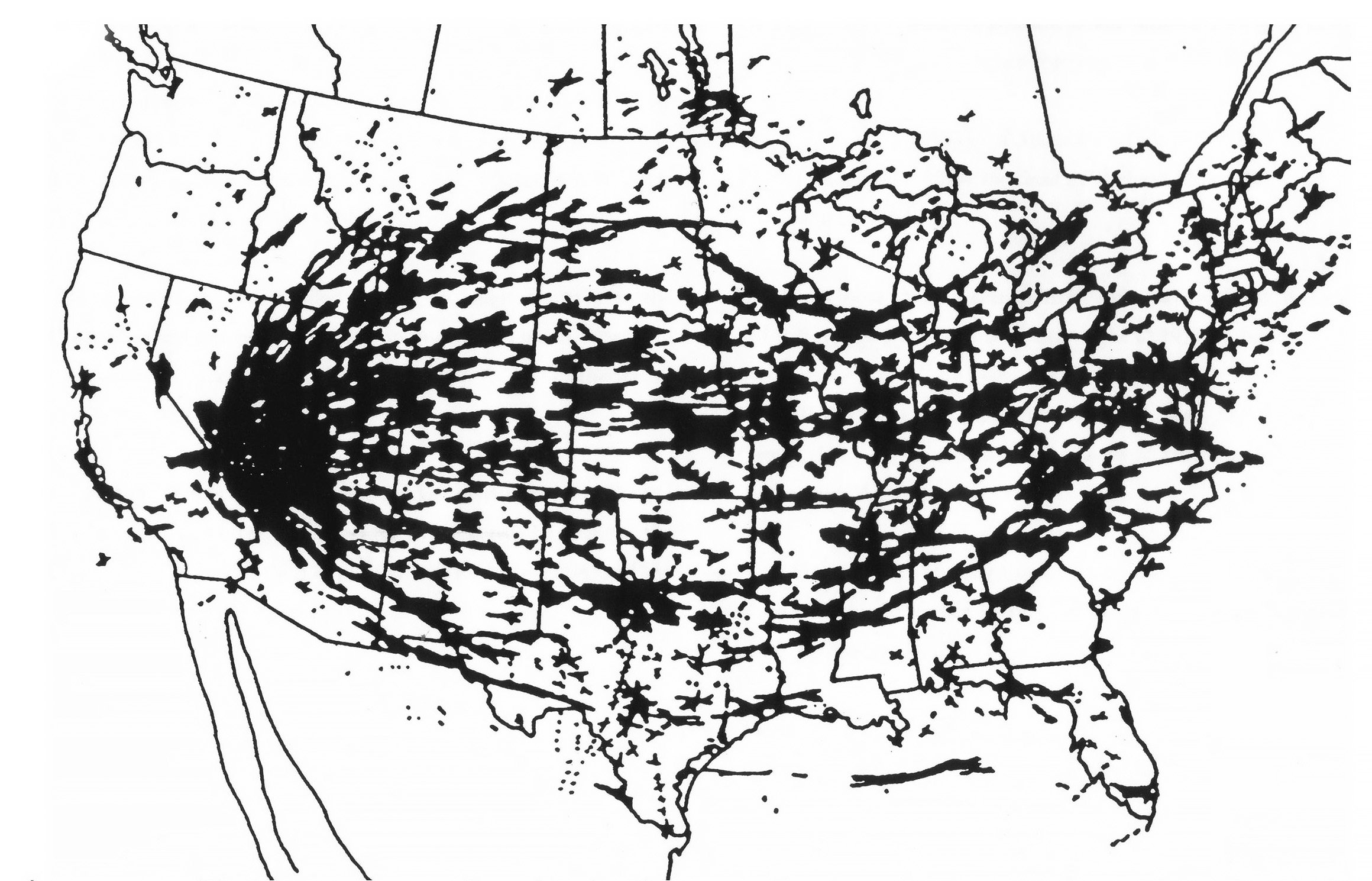

Over the next days, this radioactive death shroud would drift eastward over much of the Interior West from its inception at Yucca Flat. Eventually, it would sweep over the Great Lakes region toward Montreal, Quebec. Other trajectories would head southeast into Arizona, skirting Texas’ Gulf Coast until the cloud rendezvoused with central Florida. Another path headed northeasterly over central Nevada and beyond.[1] Geographical points in between, hundreds of miles from ground zero, would become random “hot spots” depending on the frivolity of prevailing winds or if, perchance, the fallout was driven down to earth by rain or snowfall after the “gadget” had been unleashed. But the “low-use segment of the population” living directly downwind would suffer the brunt of this deadly fallout. If someone dared to ask whether or not the tests could harm them, those in charge would smugly ensure them otherwise, slyly suggesting that they must be unpatriotic, perhaps even a Communist or simply out of their mind. Life in these rural parts would appear to return to normal while collective anxiety festered with nearly everyone who had experienced these spectral events. But more disturbing is the fact that those charged with administrating the U.S. government’s nuclear testing program had knowingly orchestrated this monstrous public health deception.

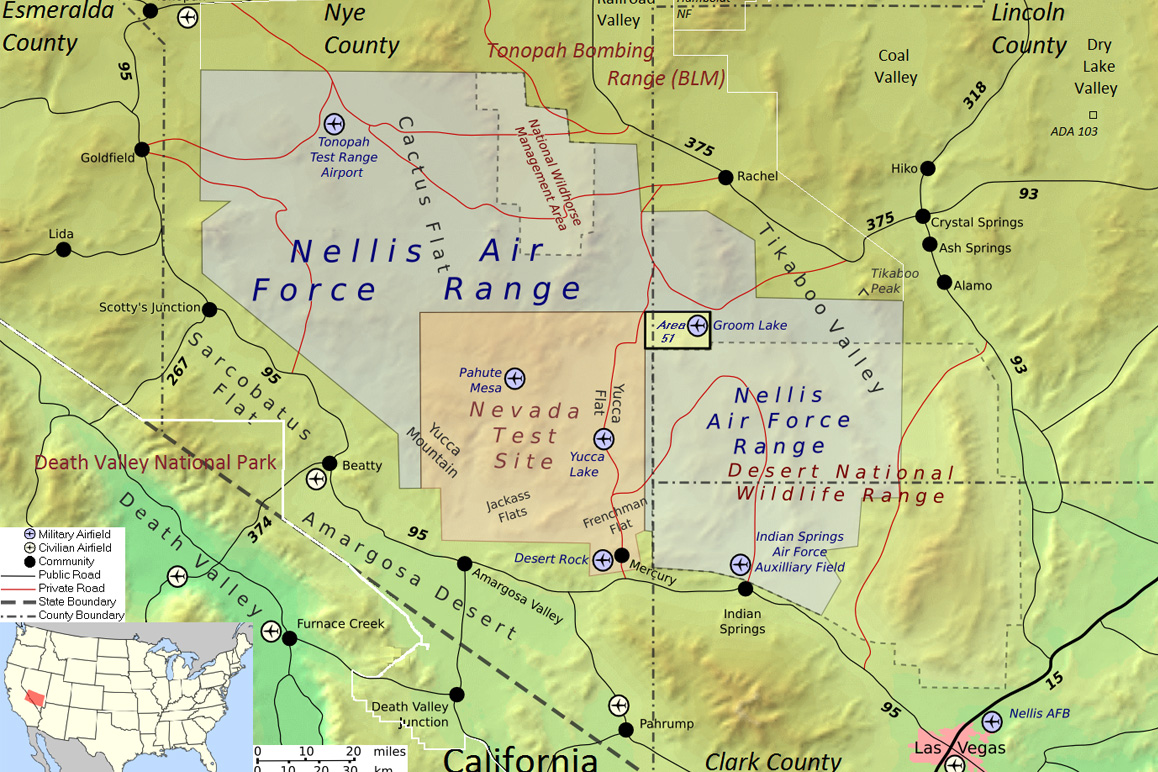

For eleven years, beginning on January 27, 1951, the U.S. government conducted 100 atmospheric atomic weaponry tests at the 1,350-square-mile Nevada Test Site (NTS), located sixty-five miles northwest of Las Vegas. These “shots” occurred like clockwork until the international Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was signed on August 5, 1963, after the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union agreed to suspend their aboveground atomic weaponry programs.[2] It is estimated 12 billion curies of radiation were released during atmospheric testing conducted between 1951 and 1963 at the NTS. In comparison, the Chernobyl disaster released an estimated 81 million curies of radiation when the No. 4 reactor melted down in 1986. [3] Atmospheric testing occurring between 1951 to 1958 at the NTS likely contributed to 186,500 crude deaths and 63,500 cancer deaths in the twenty-year window after testing began.[4] Underground testing would continue uninterrupted with 921 underground atomic weaponry tests that were regularly detonated as late as 1992.[5] Public awareness and the abrupt end of the Cold War gradually forced the Department of Energy to abandon the program entirely in 1996 under the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.[6]

The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was established in 1946, after World War II had ended, to “monitor the peacetime development of atomic science and technology.” The title benignly suggests nuclear energy advancement as the goal, but the AEC’s primary agenda was to oversee and facilitate atmospheric nuclear weaponry testing—staged thereafter at the Pacific Proving Grounds in the Marshall Islands. Once given the green light, the AEC moved quickly. By mid-1946, a pair of massive atomic tests named Operation Crossroads had been conducted to observe the effects of nuclear weapons on naval warships. These disturbing “tests,” which are better described as “bombs,” signified to the world that weapons of war, rather than the peacetime production of nuclear energy, were the AEC’s core agenda.

The first Operation Crossroads test, codenamed Shot Able, was a twenty-three-kiloton detonation on June 30, 1946, at the Bikini Atoll.[7] Shot Baker would follow. Two years later, the AEC would argue that a continental staging area was required for atomic testing because the Pacific Proving Grounds had become logistically cost-prohibitive due to cancellations from unpredictable weather, along with the arduous task of staging these monumental and costly experiments in a distant location in the Pacific Ocean. Concerns that the Pacific site could be prone to enemy attack also figured largely for the military in its push to find a tactical domestic test site. Officials secretly launched Project Nutmeg in their effort to find suitable sites to stage smaller, but no less destructive, atomic tests within the contiguous U.S.

The AEC quietly considered six potential locations, in Alaska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Carolina, Texas and Utah. Three were short-listed: Alamogordo-White Sands Missile Range, where the twenty-two-kiloton Trinity Test occurred on July 16, 1945; the Dugway Proving Grounds in western Utah; and two areas in Nevada. The Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range became the preferred site. As an operational airbase with existing infrastructure positioned within the sparsely populated arid region of Nevada’s Great Basin, the location featured rugged desert terrain and nearly impenetrable mountain ranges that kept the curious public at bay. Numerous dry lakes would be ideal for strategic target and staging areas. Las Vegas, an hour’s drive south, would provide housing and urban amenities for workers, scientists, military personnel and support staff.

Potential public health hazards arising from nuclear fission byproducts released into the environment from atomic testing were low on the list of AEC priorities—officials were confident that their meteorologists would determine the best days to conduct tests to minimize the chance that populated areas, such as Las Vegas and Southern California, would be subject to radioactive fallout. Rural downwind populations bordering the proving ground, in Nevada and Utah, would not be so lucky. The Beehive state’s western region was home to a sprinkling of miners, ranchers, farmers and their families, along with settlements of Western Shoshone and Southern Paiute, whose ancestors had long occupied the area well before Euro-Americans had laid claim to it. Although not much of a surprise, the region’s richly biodiverse non-human communities of flora and fauna had been deemed an ecological sacrificial zone.

On December 18, 1950, President Harry Truman ordered the transfer of a 680-square-mile portion of the Las Vegas Gunnery and Bombing Range for use as the Nevada Proving Grounds.[8] Three weeks later on January 11, 1951, a handbill printed with red type was hastily posted in areas bordering the test site stating “from this day forward the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission has authorized to use part of the Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range for test work necessary to the atomic weapons development program.” The flyer stated that all experimental nuclear detonations would be “carried out under controlled conditions” and that “no public announcement of the time of any test will be made.” Additionally, it declared “health and safety authorities have determined that no danger from or as a result of AEC activities may be expected outside the limits of the Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range. All necessary precautions, including radiological surveys and patrolling of the surrounding territory, will be undertaken to insure [sic] safety conditions are maintained.”

Within sixteen days, on January 27, 1951, Operation Ranger would commence when Shot Able, a one-kiloton airdropped atomic bomb (equivalent to 1,000 tons of TNT) was let loose 1,060 feet over the dry playa nicknamed Frenchman Flat.[9] From this day forward a new phase of the atomic era had begun.

Miss Atomic Bomb, Sands Copa Girl Lee Merlin, posing in the Las Vegas desert, May 24, 1957. Credit: Don English/Las Vegas News Bureau.

Las Vegans generally welcomed the event without much thought, although windows of homes and businesses had been shattered from the blast. After all, national security was at stake. Atomic testing was perceived as a patriotic necessity to both thwart and stay ahead of the scientific and technological advances of Cold War communism.[10] Plus, testing would provide thousands of local, well-paying federal government jobs that would, in turn, infuse the local economy with billions of dollars over time.

From the start, Las Vegas boosters knew atomic testing offered tourism opportunities. Just a few days after Able was dropped, the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce sent out a series of press releases promoting explosions as tourist attractions and began distributing calendars with scheduled detonation dates along with the best locations to observe them. Families would gather in prime viewing areas as close as AEC officials would allow them to do so. Overnight, Las Vegas became “Atomic City.”

In Las Vegas proper, early-dawn bomb parties became the rage. Drunken gatherings started around midnight and would climax by dawn once the nuke was launched. Bartenders at the Binion’s Horseshoe, Desert Inn, Flamingo, Sands and other mob-funded casinos devised their variations of the Atomic Cocktail to be sipped while watching the explosion in real-time at rooftop lounges or poolside. Exuberant showgirls vied for the crown of “Miss Atomic Bomb” while donning bathing suits outfitted with voluptuous cotton atomic mushroom clouds. One caption on a publicity photograph of Last Frontier dancer Candyce King read “radiating loveliness instead of atomic particles.”[11]

By April 1952, as the second Tumbler-Snapper test series commenced, detonations were broadcast live on television, with journalists and film crews gathering at News Nob, a rocky outcrop at the proving ground where they and other privileged civilians could view the blast. All branches of the military would participate in “observer programs, tactical maneuvers, scientific studies, and support activities” during these tests, with many at extremely close range to ground zero. Like clockwork, a mushroom cloud would appear on the Nevada horizon nearly every three weeks until 1958, when the international community agreed to halt atmospheric nuclear testing for three years. Nobody stopped to consider whether or not the fallout could be harmful or even deadly—especially since the AEC and the Department of Defense had gone out of their way to ensure the public that these atomic tests were completely safe.

As the first faint streaks of dawn poked over the distant hills the blast came. A vivid flash of light pierced the desert darkness and lighted up the entire countryside. It lasted but a moment or two then was gone. All eyes turned toward the spot where the bomb had exploded. They saw a big ball of furiously churning fire, smoke, sand and debris rapidly rising from the ground in huge, rolling waves. The afterglow remained for several minutes while the mushroom cloud continued to rise then drift away and apart. Then sun was still below the horizon but daylight was coming fast. Broad streaks of sunlight slanted over the mountain tops like ghostly fingers clawing at the heavens. Rumbling of the shock wave continued for nearly five minutes, bouncing back and forth from one mountain wall to another. —Nevada Highways & Parks, 1953 June-December issue

On May 19, 1953, another pre-dawn blast occurred at 5:05 a.m. on Yucca Flat. Code named Harry, this four-ton shot was part of Upshot-Knothole, a series of eleven atmospheric tests conducted over March into June of that year. Harry was number nine. Climax, the final shot of Upshot-Knothole, would be detonated at 1,334 feet in the air from a B-36 bomber on June 4, 1953. Climax, as its name implies, was the most robust bomb of the group, yielding a massive sixty-one kilotons. Still, Climax would not be the most infamous detonation of the series—Harry would take this dubious honor.

Before Upshot-Knothole (click for film footage), twenty-nine atmospheric detonations had already taken place at the stateside Nevada Proving Ground. AEC officials considered these “low-yield affairs” that produced only moderate levels of off-site fallout. Harry was the exception. After the shot had gone awry it would be sarcastically renamed “Dirty Harry.”

Set alight atop a 300-foot tower, Harry incorporated an untested hollow-core bomb design with a relatively small amount of fissionable material designed by Los Alamos theoretical physicist Ted Taylor. In theory, this would create a much larger explosion. Upon detonation Harry did just that—it vaporized the steel support structure churning up 1,734 tons of earth as the huge fireball plummeted to the ground yielding 32.4 kilotons—twenty kilotons more than scientists had expected.[12] The radioactive particles of sand, earth, rock and steel were sucked up “like a giant vacuum cleaner” into the developing mushroom cloud. As it gained altitude, the rose-colored cloud began traveling directly east towards St. George, Utah. At the time, an estimated 16,200 people were to be irradiated in the immediate area.

Scientists estimate that Dirty Harry delivered 300-350 milliroentgens per hour of measurable ionizing radiation directly onto St. George—comparable to what residents of Pripyat, Ukraine, were exposed to after the Chernobyl Reactor meltdown occurred on April 26, 1986.[13] One expert noted that if a rainstorm had ensued after the shot’s fallout reached St. George, it would have “killed half or all of the people in town.”[14] Notably, Dirty Harry generated the largest amount of external gamma-ray exposure of any single atomic test launched in the contiguous U.S.[15] Without a doubt, Upshot-Knothole, with its 252 kilotons’ worth of deadly nuclear fission byproducts, was the most brazen and reckless series of atomic weaponry tests ever to be conducted during the AEC’s twenty-nine-year history.

Dirty Harry’s ominous cloud arrived unannounced by 8:50 a.m. Frank Butrico, the AEC radiation monitor stationed in St. George, was dumbfounded when his Geiger counter went completely off the scale. At the time, residents of St. George were going about their normal business. Children were playing outdoors during morning recess, housewives were shopping, and, across the wider region, farmers were tending their fields while livestock grazed. By the time Butrico was able to alert city authorities to tell the public to remain indoors, many of St. George’s 4,500 residents had been unknowingly exposed to Dirty Harry’s peak fallout. After all, this was a rural community of ranchers and farmers who spent their working hours outdoors. Residents of these sparsely populated areas would not receive the word of the contamination until several days later, if at all. Nearby Cedar City, along with other small towns sprinkled throughout western and southwestern Utah, eastern Nevada and northwestern Arizona, would be heavily irradiated.

In the days following the blast, beta radiation symptoms and sickness began to appear. Facial burns, rashes, skin lesions and blisters on exposed parts of the body were reported to AEC monitors. Overall malaise including nausea, vomiting, fever, diarrhea and lethargy were also noted. In some hard-hit areas, people suffered hair, fingernail and toenail loss within days of the event. Agatha Mannering, who hadn’t heard the news reports that day, had spent the afternoon weeding her garden. By sunset she was ill. The next morning “her skin and scalp were on fire.” A few days later hair began to fall out.[16] Most residents, including their family doctors, weren’t familiar with the symptoms of radiation exposure, so the mysterious illnesses were misdiagnosed or not reported at all. Backyard vegetable gardens and community drinking water sources were riddled with hazardous radioactive contamination that would be consumed or drunk at the next meal. Birds and animals would suddenly perish. Only many years later, after these “downwinders” understood what they and their loved ones had been exposed to, did they realize the horrible truth.

Most alarming was the radioiodine contamination of grazing pasture that would, in turn, be consumed by local dairy cattle and passed on unknowingly to those drinking the cows’ fresh milk.[17] Children, for the most part, were the main consumers. Iodine-131 is one of many radioisotope byproducts produced during a nuclear fission chain reaction. It is a particularly dangerous short-lived radioactive beta-emitter, with a half-life of about eight days. In other words, Iodine-131 radioactivity is stabilized or reduced over time. Within two months and up to a year, radioiodine will fully decay. During this era of atmospheric atomic testing, prodigious amounts of Iodine-131 were released into the atmosphere worldwide.

Mother’s breast milk is known to further concentrate radioiodine. Infants nursing at the time of the atomic tests received considerable doses of radioiodine because their thyroid is smaller than an adult’s, making the ratio of the bioaccumulation in their organs far higher. Plus, if the children’s mother drank contaminated milk along with irradiated vegetables, meat and other food, the dose was further concentrated. Radioiodine does not flush out of the body; rather, it is stored in the thyroid tissue, which normally absorbs non-irradiated iodine to function properly. Thyroid cancer caused by this type of exposure may not appear until many years later.

AEC officials would downplay the contamination, telling Butrico and other field monitors that radioactive fallout from Dirty Harry was negligible and “well within the limits of safety.” [18] (The AEC compared the exposure to getting an X-ray.) They were, in turn, advised to communicate to the public that the fallout was not harmful to either humans, animals or crops. Residents became suspicious when people were advised to stay indoors or were stopped at roadblock checkpoints to have their contaminated vehicles washed down. Over time, it would be estimated that over 1,000 kilotons of iodine-131 had been released from the Nevada Test Site during repeated atmospheric testing.[19]

Realizing a public-relations disaster would soon erupt, the AEC hurried to produce a newsreel along with a printed pamphlet featuring crude cartoon illustrations titled Atomic Test Effects in its attempt to assuage the public’s very legitimate concerns. Released in April 1955, the propaganda-riddled film Atomic Tests in Nevada featured many St. George residents, including hardware store owner Elmer Pickett, who would eventually lose sixteen family members to various forms of cancer and disease brought on by the toxic fallout. In Carole Gallagher’s pressing 1993 photo book documenting oral histories of these downwinders titled American Ground Zero: The Secret Nuclear War, Pickett plainly states that two-thirds of the people from St. George that volunteered to appear in the film had died of cancer.[20]

When the Upshot-Knothole series began, an estimated 11,710 sheep were grazing across Lincoln County, Nevada and western Utah. Some of the grazing animals were as close as forty miles from ground zero. The sheepmen herding the animals weren’t notified about impending atomic tests much less warned on the possible side effects of the radioactive fallout to themselves or their livestock. Because sheep travel slowly, about six miles per day, it would be impossible for sheepmen to move their flocks out of harm’s way even if they had received a forty-eight-hour notice. Nor was it lost on AEC officials that these seasonal herding activities were well underway. Some critics assert that AEC officials may have covertly planned to use the sheepmen and their livestock for unwitting fallout test subjects.

For example, secret AEC studies conducted before the 1953 tests had confirmed the harmful effects of radioactive fallout on livestock and other animals. Classified reports of the studies were circulated among AEC scientists and officials. The information contained was fiercely suppressed from public view for obvious reasons—doing so could shut down the AEC’s entire atomic testing program. So, the decision was consciously made not to delay or stop atomic testing for any reason.

The Bullochs, a Mormon sheep-ranching family with deep generational roots in Cedar City, Utah, wintered their sheep on rangeland west of Alamo, Nevada—a mere stone’s throw from the northeastern border of the proving ground. Every October, the men herded their flocks 150 miles westward to their winter grazing allotment and then back to lambing yards in western Utah during early spring of the following year. As brothers Kern and McRae Bulloch were preparing to begin the slow journey back to Cedar City, the 24.4 kiloton tower detonation Nancy was unleashed on March 24, 1953—a month and a half before Dirty Harry was to be exploded. Significant atmospheric fallout followed in her wake.

We were on the trail home from out Nevada range into our Utah range and I was out on the saddle horse with this herd of sheep just sitting…kind of watching the sheep. They were grazing and these airplanes came over and all at once this bomb dropped—I wasn’t expecting it…The cloud came up and drifted over us and a little bit later that day some of the army personnel came through and said, ‘Boy, you guys are really in a hot spot.’ —Kern Bulloch, sheep rancher, The Forgotten Guinea Pigs, August 1980

Bulloch’s account took place at Coyote Summit, accessible today from a stretch of the “Extraterrestrial Highway” on Nevada State Route 375 between Crystal Springs and Rachel, near Bald Mountain in the Groom Range. The AEC field monitors the men encountered that fateful day were concerned enough to radio higher-ups, asking what to do about the situation. They were told to forget the men and their livestock—officials feared a public-relations nightmare and, besides, what were they going to do with all those sheep? So, the monitors drove off in their Jeeps in the cloud of radioactive dust, leaving the men to fend for themselves and their animals.

As the herd of roughly 2,000 sheep moved easterly toward Utah, the animals foraged on open range vegetation laden with iodine-131 and other radioactive contaminants. Most of the ewes traveling with the flock were pregnant and would give birth within a month, but some began to do so along the trail. Alarmingly, the Bullochs began to witness firsthand the deadly effects of fallout exposure as ewes began to spontaneously abort their lambs, with most dying along the trail. Wool would slough off the sheep’s bodies in huge clumps. The ones still pregnant that made it back to the yards delivered lambs “with little legs, [and] kind of pot-bellied…some of them didn’t have any wool, kind of a skin instead of wool,” stated Kern Bulloch.[21] McRae would later describe to Carole Gallagher how lambs were “born with their hearts outside of their bodies, skin like parchment so you could see right inside to their organs.”[22] Continuing on, he painfully shared how they piled the lambs’ little bodies up so high that the mountain of death would reach the roofline of the lambing sheds. Sickened full-grown sheep would appear as if in a stupor “frozen like statues” just before they fell over dead.[23]

The Bullochs and other ranchers of the region noted within days of the tests burn-like lesions on their animals’ bodies, limbs, faces, ears, necks and mouths—where the livestock had been in direct physical contact with contaminated vegetation as they grazed. Others found dark-hided cattle, horses and black-wooled sheep exhibiting white spots on their backs where “hot” fallout particles had burned into their hides. At first, they were baffled by the cause of their livestock’s afflictions, but when further Upshot-Knothole tests followed, causing the similar afflictions, it became clear to them that the atomic blasts were to blame.

By June 1953, unprecedented sheep deaths were being reported regionally—4,390 sheep had died in the greater St. George area, including 1,420 lambing ewes and 2,970 stillborn or aborted lambs. Because the ranchers were not notified about the actual cause of the mortalities many sold the carcasses in their desperation to recoup some compensation for their financial losses. Contaminated meat likely made its way into the human food chain. Heavily radiated wool salvaged from the carcasses was also sold at market. Cedar City sheep rancher Annie Corry, whose entire flock perished from repeated fallout episodes, stated in Gallagher’s book her concern for “those fellows tromping that wool full of radiation.” Like her doomed ewes and lambs, Mrs. Corry would succumb to radiation-induced leukemia as would her daughter years later.[24]

Areas of the continental U.S. that were crossed by more than one radioactive cloud resulting from aboveground nuclear detonations conducted at the Nevada Test Site during 1951-1963. Miller, Under the Cloud, 444.

Two AEC veterinarians assigned to look into the sheep mortalities concluded in their preliminary reports, after conducting autopsies of deceased animals, that the symptoms and consequent deaths were in line with what AEC scientists clearly understood from previous classified radiation experiments. They were referring to internal studies of cattle exposed to fallout during the 1945 Trinity Test in New Mexico and those conducted at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation by Dr. Leo Bustad. During Bustad’s Hanford experiments, begun in 1950, late-stage pregnant sheep were fed pellets laced with varying dosages of Iodine-131. Ewes gave birth to physically deformed, weak or stillborn lambs. Their “thyroids, and those of their offspring, showed virtually complete destruction.” [25] The majority of lambs that survived birth died shortly afterward. Bustad’s experiments involving irradiated fetal lambs replicated “signs and conditions almost identical” to what the Utah sheep had exhibited, so it was clear that illnesses, disease, and death from exposure to low-level radiation doses had been previously documented and circulated within the internal AEC scientific community. [26]

The initial scientific review of the sheep deaths was conducted ten weeks after the sheep had succumbed, so it can be concluded that the sheep’s initial radioiodine exposure levels were much higher. Surviving sheep were said to be “hotter than a two-dollar pistol.” Even bones of sheep that had died months earlier continued to emit extremely high levels of radiation.[27] Dr. Stephen Brower, Utah’s Iron County agricultural agent-intermediary working with the AEC veterinarians, asked for a copy of the final report but was told that it had been confiscated by AEC higher-ups. Brower later testified during the 1979-80 House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce hearings that the veterinarian who authored the report told Brower that AEC officials directed him “to rewrite it and eliminate any reference to speculation about radiation damage or effects.” The veterinarian, Dr. R.E. Thompsett, was promptly removed from the investigation as was the other, Dr. Robert Veenstra.

During the House hearings, Dr. Brower shared a reprehensible account of Doug Clark, a Cedar City sheepman who had suffered enormous livestock losses due to fallout resulting from the atomic tests. After Clark had raised informed questions with the AEC’s scientific representatives on whether or not the fallout had caused his animals’ deaths, he was met with disrespect and belittlement. Dr. Brower, quoted in The Forgotten Guinea Pigs (the 1980 House report documenting the 1979-80 hearings), stated that the AEC representative “rather than answering the question, called [Clark] a dumb sheepman [and] told him he was stupid—that he couldn’t understand the answer if it was given to him and berated him rather than answering the question.”[28] Mr. Clark, who also served his community as a city council member, was so stressed from this ordeal he suffered a massive heart attack after the meeting and died. Brower was told off-record by Dr. Paul Pearson, the head of AEC’s Biological Medicine Division, “that the AEC under no circumstances could afford to have a [financial] claim established against them to have that precedent set.”[29]

Instead, the AEC officially attributed the sheep mortalities to malnutrition and poor management caused by their owner’s own negligence. The AEC would additionally state that there is “no causal connection between the sheep’s exposure to radioactive fallout emitted during the Upshot-Knothole test series and their deaths.”[30]

A group of Utah sheep ranchers led by the Bullochs would wholeheartedly disagree. The Bullochs and other plaintiffs representing sixteen ranching families took their case to federal court in 1956, requesting $177,000 in damages.31 The sheepmen, unfortunately, lost the lawsuit when Federal District Judge A. Sherman Christensen agreed on behalf of the federal government. The AEC, through its ongoing misrepresentation campaign and abetting expert witnesses, had effectively suppressed the true cause of the sheep’s demise. It would be more than twenty-six years before a second case would make its way to federal court in 1982, after the Carter administration had ordered AEC’s classified documents made public through the Freedom of Information Act.

The simplest explanation of the primary cause of death in the lambing ewes is irradiation of the ewe’s gastrointestinal tract by beta particles from all of the fission products that were ingested by the sheep along with open range forage. Irradiation of the sheep’s thyroid and other internal organs by specific nuclides included in the fallout, coupled with the severity of range conditions that year were undoubtedly contributing factors. —Dr. Harold Knapp, Sheep Deaths in Utah and Nevada Following the 1953 Nuclear Tests.

The 1979-80 House hearings finally revealed the smoking gun(s) that supported the sheepmen’s original lawsuit. When their case was brought back to Christensen’s court, he ordered a new trial—ruling that the AEC and their lawyers had “perpetuated a fraud against the court.” Declassified documents and testimony from the hearings included a recent fifty-five-page report by former AEC Division of Biology and Medicine Fallout Studies researcher Dr. Harold Knapp, who began investigating “hot spots” throughout the continental U.S. for the AEC in 1960. Knapp would testify at the hearings on behalf of the sheepmen, but this wasn’t the first time he had stood up against his former employer.

Dr. Knapp had broken ranks with the AEC in 1963 after his AEC-critical “Knapp Report” drew consternation and eventual censorship from AEC leadership. The cunning Dr. Gordon Dunning, who, as Knapp’s superior, masterminded much of the lies and suppression of information that emerged from the AEC during years past, would lead the charge to discredit Knapp’s findings.[32] Knapp’s pivotal study had exposed the unprecedented depth of deceit perpetrated by Dunning and his colleagues in their effort to cover up their dirty atomic testing. Technically dismissed and internally suppressed by these men, Knapp’s meticulously researched data shows how St. George area infants and children, who consumed fresh milk within days of a single 1953 atmospheric atomic test, received doses of iodine-131 as high as 150 to 750 times what was deemed annually permissible at the time.[33]

Sadly, Judge Christensen’s order for a new trial in the Bulloch case was reversed by the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver in 1983. Notably, the judge who wrote the appellate decision had previously acted as counsel for the Los Alamos National Laboratory. By then, the U.S. government had spent “a quarter of a million [of taxpayers’] dollars a day” to fight the plaintiff’s lawsuit.[34] Ironically, it would have been cheaper for the federal government to pay the sheepmen what they had initially requested in damages. However, the most revealing aspect of the proceedings was the prescient, if not official, explanation of the sheep deaths. Undoubtedly, this revelation confirmed that humans, too, were exposed to similar amounts of deadly radiation.

This multi-part dispatch illuminates the deeply troubling legacy of atomic weaponry testing at the Nevada Test Site. It is my desire that all readers delve further into this dark and complicated chapter of U.S. history. I have provided a short selection of previously published books and websites sourced for this dispatch.

- John G. Fuller, The Day We Bombed Utah (New York: New American Library, 1984).

- Richard L. Miller, Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing (New York: The Free Press, 1986).

- Carole Gallagher, American Ground Zero: The Secret Nuclear War (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1993). The most important photographic and historical document outlining first-person accounts of downwinders affected by the United States continental nuclear weaponry testing program’s reckless activities.

- Rebecca Solnit, Savage Dreams: A Journey into the Landscape Wars of the American West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

- Valerie L. Kuletz, The Tainted Desert: Environmental and Social Ruin in the American West (New York: Routledge, 1998).

- Sarah Alisabeth Fox, Downwind: A People’s History of the Nuclear West (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

- Andrew G. Kirk, Doom Towns: The People and Landscapes of Atomic Testing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017). This is a graphic history of the Nevada Test Site. Illustrated by Kristian Purcell.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

The original title of this dispatch series, Death by Geography, was first coined by Carole Gallagher in American Ground Zero (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1993) on page xxxii.

[1] This is a brief geographical description of Harry’s four fallout trajectories illustrated in Richard L. Miller, Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing (New York: The Free Press, 1986), 455. The Harry shot, part of the Upshot-Knothole test series, was detonated on May 19, 1953.

[2] As negotiators struggled over differences, the United States, United Kingdom and the Soviet Union suspended nuclear tests—this temporary moratorium lasted from November 1958 to September 1961. The treaty prohibited nuclear weapons tests or other atomic explosions underwater, in the atmosphere, or outer space.

[3] Keith Meyers, “Some Unintended Fallout from Defense Policy: Measuring the Effect of Atmospheric Nuclear Testing on American Mortality Patterns,” University of Arizona, Tucson, June 29, 2021. The 2021 version of this paper, originally published in 2017 as part of Meyers’ Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Arizona’s Economics program, is currently under journal review. See https://www.keithameyers.com/research.

[4] In the paper’s abstract, Meyers states, “I find evidence that fallout from these nuclear tests contributed to substantial and prolonged increases in mortality across the continental U.S., and that these increases occurred in places far beyond the region surrounding the testing location.” Earlier scientific and medical studies, including the 1999 National Cancer Institute, report 49,000 thyroid cancer cases and a few thousand deaths from these same tests.

[5] Exact NTS test numbers vary depending on the source. “Nevada Test Site,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nevada_Test_Site.

[6] The Department of Energy is formally known as the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).

[7] The Bikini Atoll is the ancestral homeland of Pacific Islander Marshallese, who reluctantly evacuated their homes so the U.S. government could conduct twenty-three of the sixty-seven nuclear tests at the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958. For further reading, see Suzanne Rust, “How the U.S. betrayed the Marshall Islands, kindling the next nuclear disaster,” Los Angeles Times, November 10, 2019. https://www.latimes.com/projects/marshall-islands-nuclear-testing-sea-level-rise/

[8] The Nevada Proving Grounds is the former name of the Nevada Test Site (NTS). The Nevada National Security Site (NNSS) is 1,350 square miles today. The Nevada Test Site’s expansion occurred in 1958, 1961 and 1964, with the Pahute Mesa added in 1967. Nellis Air Force Base (formally the Las Vegas Gunnery and Bombing Range) flanks the NNSS to the west, north and east.

[9] The 1951 inauguration of continental atomic weaponry at the NTS tests also included the Operation Buster-Jangle series. The first shot of the series was Able on October 22, 1951.

[10] The Soviet Union had conducted its first successful atomic test in 1949.

[11] “Miss Atomic Bomb” flyer from the National Atomic Testing Museum.

[12] John G. Fuller, The Day We Bombed Utah (New York: New American Library, 1984), 28.

[13] “Nevada Test Site Downwinders,” Atomic Heritage Foundation, July 31, 2018, https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/nevada-test-site-downwinders.

[14] Stewart Udall, “‘Big Lie’ Mushroomed into Death Downwind,” Deseret News, May 25, 1994.

[15] “The Upshot-Knothole series produced 50 percent of all the radiation spread over a 300-mile radius during the entire history of nuclear weapons testing at the Nevada Test Site. Harry contributed 75 percent of this total contamination.” “Nevada Test Site Downwinders,” Atomic Heritage Foundation July 31, 2018, https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/nevada-test-site-downwinders See also: “Operation Upshot-Knothole–Harry Test,” Nuclear Weapon Archive, June 19, 2002, https://www.nuclearweaponarchive.org/Usa/Tests/Upshotk.html.

[16] Miller, Under the Cloud, 176.

[17] Ninety percent of iodine (or, for that matter, radioiodine) is absorbed into the bloodstream within fifteen minutes of consuming food or, in a cow’s case, forage contaminated with this chemical element. Miller, Under the Cloud, 360.

[18] Glenn Cheney, They Never Knew: The Victims of Nuclear Testing (New York: Grolier, 1996), 39. In 1982, Frank Butrico shared his recollection of the event during a landmark wrongful-death suit filed by twenty-four people with cancer and their relatives from Utah.

[19] This is before any reliable data on radionuclide levels had been obtained or collected in off-site communities by the AEC. Scott Kirsch, “Harold Knapp and the Geography of Normal Controversy: Radioiodine in the Historical Environment,” Osiris, 2nd Series, 19 (2004): 167-181.

[20] Carole Gallagher, American Ground Zero: The Secret Nuclear War (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1993), 150.

[21] Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce U.S. House of Representatives and its Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, The Forgotten Guinea Pigs: A Report on Health Effects of Low-level Radiation Sustained as a Result of the Nuclear Weapons Testing Program Conducted by the United States Government, 96th Cong., 2nd session. (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office), vii.

[22] Gallagher, American Ground Zero, 267.

[23] Fuller, The Day We Bombed Utah, 25.

[24] Gallagher, American Ground Zero, 272.

[25] Michele Stenehjem Gerber, On the Home Front: The Cold War Legacy of the Hanford Nuclear Site (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), 97-98. See also Forgotten Guinea Pigs, 9-13.

[26] For further reading, see https://hanfordproject.com/experiments.html.

[27] Gallagher, American Ground Zero, 267.

[28] The Forgotten Guinea Pigs, 6.

[29] The Forgotten Guinea Pigs, vii.

[30] The Forgotten Guinea Pigs, 4.

[31] Jim Kichas, “Downwind in Utah,” Utah Division of Archives and Record Search, June 26, 2015. https://archivesnews.utah.gov/2015/06/26/downwind-in-utah/ Other articles state $220,000 in damages. Also, see Stewart Udall, “AEC Concealed Cause of Sheep Deaths,” Deseret News, May 24, 1994.

[32] Udall, “‘Big Lie’ Mushroomed into Death Downwind.”

[33] In late 1962, Dr. Knapp was investigating the dairy/radioiodine connection when the AEC detected alarming levels of Iodine-131 at monitoring stations after the 104-kiloton hydrogen bomb Sedan (Operation Plowshare) and Small Boy (Operation Sunbeam) underground tests had taken place that summer. Due to the controversy his report generated within AEC, Knapp promptly resigned from his position and went to work for the Pentagon. Eight months after the international community signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, Knapp’s groundbreaking study was finally made public. For further reading, see Kirsch, “Harold Knapp and the Geography of Normal Controversy,” 168-169.

[34] Dan Bushnell, the sheepmen’s lawyer throughout their thirty-year legal ordeal, commented that this was how much the U.S. government was spending on the federal attorney’s fees to fight their case. Gallagher, American Ground Zero, 269.

The banner image above is often misattributed as Shot Priscilla, a thirty-seven kiloton balloon drop of Operation Plumbbob detonated on June 24, 1957. Nuclearweaponarchive.org states that the image is Grable, a fifteen kiloton gun-type fission weapon shot from a cannon on May 25, 1953, in Area 5 of the Nevada Test Site.