Their publicized disappearance set into motion a series of revelations concerning deep time, interconnected hydrogeological sublimity, time-traveling Indigenous shamans, distant seismic events, genetic conundrums, capitalistic greed and consequent environmental exploitation. At the center of this saga is a tiny endangered fish at the threshold of existence.

But before we move along too far let’s get back to the plight of those boys. Indulge me for a moment and imagine their fateful story beginning something like this:

Arriving at their destination, the foursome hiked up a hot, barren hillside overlooking the large-scale ranching operation that would nearly erase the ancient spring complex of Ash Meadows within a few short years. A well-trodden trail led to the entrance of a limestone chasm that had opened to the heavens some 60,000 years ago after some likely impressive seismic event caused the roof of the cave to collapse inwards. The group—Paul Giancontieri, 19, a cafeteria worker at the nearby Nevada Test Site and his new brother-in-law David Rose, 20, a Las Vegas casino parking attendant, along with Bill Alter, 19, and his younger brother Jack scrambled under a fenced enclosure posted with warning signs, and proceeded to descend the thirty or so rocky feet down to a ledge where the faint, but flitting movements of tiny blue-grey pupfish could be observed swimming in the 8-by-60-foot pool if one bothered to look closely.

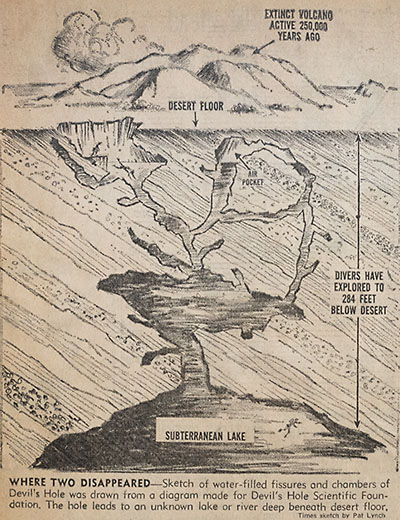

A newspaper illustration of Devils Hole based on Houtz’s original map rendering published in 1965. Jim Houtz collection.

After suiting up with scuba tanks, masks and dive lights, Paul, David and Bill dove into the womblike waters—the temperature nearly indistinguishable from that of our skin. Upon entering the pool the boys most likely disturbed the delicate algae spawning mats where the entire population of the exceedingly rare Cyprinodon diabolis continues to prosper and breed exclusively. Alter’s brother remained stationed on the ledge in case anything went wrong. Sometime after midnight, Giancontieri failed to resurface, so Rose and Alter quickly re-dove in a vain attempt to locate their missing friend. Alter frantically followed Rose some 175 feet until Rose, too, disappeared into the vast liquid darkness. The bodies of the brothers-in-law were never to be recovered.

The young men’s illicit nocturnal dive may have been inspired by a newspaper article from the previous year detailing a speleological research expedition of a massive “underground lake” below Death Valley, led by California-based professional diver Jim Houtz—who would ironically dive numerous times round-the-clock with military personnel and other volunteer divers in their futile attempt to locate the missing men until their search was called off thirty-six hours later. The only traces left of the two brothers-in-law were a mask and snorkel along with a flashlight tied to a ledge some 100 feet below that ineffectively signaled the way out of the otherworldly aquatic cave system.

Syndicated articles detailing the unsuccessful rescue effort were published nationwide. In the Sarasota Journal dated June 22, 1965, Houtz stated he had previously dived in Devils Hole around 300 times over twenty-eight trips, further commenting:

It’s beautiful in there. It goes straight down 160 feet, like a pipe, then opens into a room that is about 300 feet long, and maybe forty feet wide. The bottom of the room is about 260 feet down, then it narrows into another tube. I dived to 315 feet, maybe it’s a record, I don’t know, but at the end of the tube it opens again into something else. We don’t know what the next room is, or if it’s a room at all. It’s like infinity.

More than a century before the ill-fated men disappeared into their watery grave, Death Valley Forty-Niner Louis Nusbaumer, whose immigrant party had camped near Devils Hole in the winter of 1849, visited the formidable pool. “At the entrance to the valley to the right is a hole in the rocks which contains magnificent warm water in which Hadapp and I enjoyed an extremely refreshing bath,” he reported, also noting, “the saline cavity itself presents a magical appearance.”[1] Their guide, William Lewis Manly, mentioned in his memoirs this “miner’s bathtub,” noting the presence of some “little minus [sic] in [it],” which were first collected during the Death Valley Expedition of the U.S. biological survey of the region in 1891.

More than 9,000 years ago the Nevada Spring Culture, ancestors of the contemporary Indigenous people of the region, began their occupation of the Ash Meadows area. The Southern Paiute branch of the Shoshone, ancestors of contemporary Timbisha People, later took up seasonal residence here until they were displaced, for the most part, by Euro-American settlers after the mid-nineteenth century.

The cultural significance of Devils Hole for the Timbisha was apparent; tales arose warning children of “water babies” who would surface and swallow them if they dared to remain in the pool too long[2]. Other legends suggested that Tso’apittse, a legendary malevolent giant who dwelled at mountain springs and caves, would snatch and devour unwary victims. Myths notwithstanding, Timbisha Shoshone elders have anecdotally shared that as children they enjoyed having the pupfish “tickle [sic] their toes” while they played at the spring.[3]

Devils Hole pupfish (Cyprinodon diabolis) were first classified as a unique species in 1930 by Joseph Wales. Ichthyologist Robert Rush Miller was the first researcher to conclude that the population of C. diabolis had indeed been isolated far longer than its nearest cousin, the Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish (C. nevadensis mionectes) found less than a mile away. Miller’s subsequent and persistent studies helped to secure its listing under the U.S. Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, which had been underscored by President Truman’s earlier designation protecting the forty-acre Devils Hole as part of the Death Valley National Monument on January 17, 1952, “for the preservation of unusual features of scenic, scientific, and educational interest therein contained,” which included the tiny pupfish—the rarest fish found anywhere on the planet.

At almost an inch long, C. diabolis are the smallest known pupfish in the world. Breeding males are iridescent bluish-grey while the female is more olive drab in coloration. Although genetically similar to C. nevadensis mionectes, Devils Hole pupfish differ in that they are dwarfed and exhibit neotenous or juvenile characteristics with their large heads and eyes. C. diabolis feature other unique physical traits: breeding males have a dark band on their rounded caudal fin and both sexes lack pelvic fins. Their personality differs as well; Devils Hole pupfish are mostly laid back and males, rarely, if at all, defend their mating territories like their more aggressive cousins. Today, it is generally accepted that their distinctive morphology has resulted from intensified challenges within their extremely limited environment, which is home to the entire wild population of C. diabolis—hovering at about 100 observable pupfish—making it the smallest habitat of any known vertebrate species in the world.

Devils Hole pupfish are famous among the conservation community. As the “poster fish” for conservation biology, C. diabolis seems to defy the assertion that small, isolated populations of organisms cannot possibly persist over time. Until very recently the scientific community has commonly held that C. diabolis has endured here for at least 10,000 years—possibly up to 20,000—within this nearly inhospitable submerged cavern environment. Key to their survival is the 19-by-8-foot “shallow shelf,” a portion of the long collapsed limestone roof providing the pupfish with crucial foraging and spawning habitat. The shelf is covered with less than two feet of, on average, 92.3˚ Fahrenheit water containing very little dissolved oxygen. Although the pupfish spend most of their lives at the surface, near the submerged shelf, they will occasionally swim as far as 100 feet below its surface into the aphotic reaches of the fissure near what is called Anvil Rock. Overall, their short ten-to-fourteen-month life span hangs in a precarious balance. These tiny, seemingly resilient, wonders will be lucky to survive a newly projected 28 to 32 percent risk of extinction over the next twenty years.[4]

A Devils Hole pupfish among algae growth at the upper shelf. Photo: Brett Seymour (NPS) 2015.

This fragile ecosystem on which wild C. diabolis are completely dependent is susceptible to an array of environmental disturbances, including declining water levels primarily resulting from water withdrawals at nearby production wells. The fissure’s physical orientation, structure, amount and duration of sunlight reaching the shelf, along with many other environmental variables, control food availability and overall productivity within C. diabolis’ sole natural habitat. Combined, these factors determine the species’ resilience and its ongoing survival—month-to-month, year-to-year, millennium-to-millennium. Considering these continuous environmental impacts along with imminent climate change and other complications arising from anthropogenic activity, it is miraculous that Devils Hole pupfish have managed to flourish here at all.

How and when C. diabolis ended up in Devils Hole is a continuing mystery. Earlier mitochondrial DNA analysis suggested that Devils Hole pupfish genetically diverged from its closest relative, C. nevadensis mionectes, between 200,000 and 600,000 years ago[5], though this molecular dating technique is fraught with inconsistencies. Additionally, these dates conflict with the scientific determination that C. diabolis could not have colonized the pool before 60,000 years ago when the fissure opened up to the sky, enabling life to thrive within it through the process of photosynthesis.

Several hypotheses describe how the species emerged at this specific location, but none are scientifically confirmed. The ancestors of today’s desert pupfish are thought to have colonized the American Southwest more than two million years ago via the Colorado River and other tributaries, when a system of interconnected pluvial lakes and marshes spread across the landscape. As these Ice Age lakes and riverine systems retreated, drying out over extended periods of increasing aridity, isolated populations of various species were left to evolve in genetic isolation—including the nine known Death Valley pupfish species and subspecies, of which eight currently remain.[6] In spite of this, no firm paleohydrogeological evidence so far supports an inflow or overflow connection here from a pluvial waterbody that would have provided a conduit for colonization.[7]

Even if this were the case, the Warm Springs pupfish (C. nevadensis pectoralis) that live in the springs nearest to Devils Hole should be its closest genetic relative under this hypothesis. However, as mentioned earlier, C. diabolis is more closely related to the Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish (C. nevadensis mionectes), found in springs much farther away.[8] It is unlikely that C. diabolis populated the pool from deep within the cavern, but it remains a possibility as dissolved oxygen is fairly consistent up to a depth of 125 feet and temperature varies in only tenths of a degree at 260 feet.[9] What is left to consider is an introduction by an animal—a bird or better yet, human, as it is known that the Indigenous peoples of the region did occasionally consume pupfish, so populating the pool with them for forage could have been one of the driving factors to do so. Still, it would take an awful lot of pupfish to feed just a few individuals.

Christopher Norment, in his lyrically detailed 2014 book Relics of a Beautiful Sea, suggests that if C. diabolis was indeed introduced by humans 11,500 years ago (the date when humans are said to have arrived here) or even much later, then it may have been done as some sort of a ritualized practice.[10] Although not scientifically verifiable, I would like to personally conjecture that Indian children at play transported the pupfish from another Ash Meadows pool into Devils Hole—as I did as a young girl when collecting frog eggs in glass jars to bring home. If humans were indeed responsible for introducing C. diabolis to the pool, then it may have occurred more recently—possibly less than a few hundred years ago, as proposed by a recent scientific paper.[11] Regardless of how or when these tiny creatures arrived here, gradually over time and in their isolation, they took on a unique phenotype or particular morphological traits that have made C. diabolis the singular and prized rarity that it is today.

Ojo de Agua

During the futile rescue mission in 1965 for the missing young men, diver Jim Houtz rather exuberantly, if somewhat offhandedly, commented to the press on the sheer beauty of the underwater cave:

The sides are limestone, the most beautiful limestone I have ever seen. Greens. Blues, so blue, they are nearly white. Quartz. Bronze colors, every color in the rainbow.

Houtz was likely referring to the sinewy, undulating formations of translucent mammillary calcite etched by the ceaseless movements of endolithic borers seen on the walls of the submerged limestone cavern. He could have also been describing the shelves of protruding folia found in the air-filled chamber—called Brown’s Room—that glow like opalescent bracket fungi when exposed to artificial light. The mammillary morphology, deposited through precipitation of groundwater supersaturated with calcium carbonate (CaCO3) over a span of 500,000 years, informs paleoclimatologists through radiometric dating techniques of climatic variations over time. Additionally, it provides a firm indication of when the roof of Devils Hole caved inward, as it is known that this formation abruptly stopped precipitating some 60,000 years ago here when it was exposed to dry air and other external forces.[12] The folia, another carbonate morphology created by subtle waxing and waning of semidiurnal tidal movements and water-level changes, serve as a record of water-table fluctuations formed over the last 120,000 years.[13] Flowstone occurring above the waterline of Brown’s Room built up over time in thin, layered sheets of carbonate material like a sensuous veil of hardened alabaster flesh.

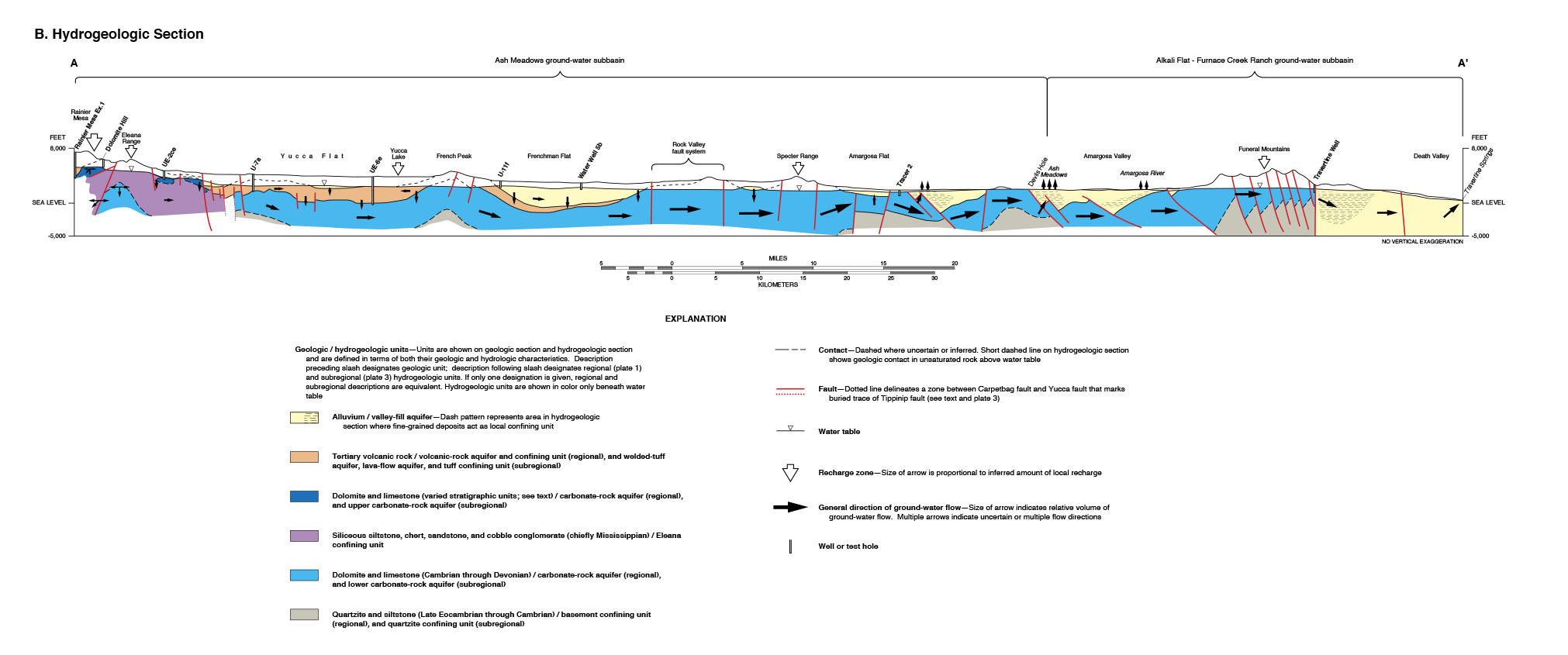

A hydrogeologic cross-section illustrating the vastness of the Death Valley Regional Groundwater Flow System (USGS).

This particular ojo de agua or as one scientific paper stated, “skylight to the water table,”[14] is a mysterious portal offering us a glimpse into deep time and the third largest carbonate aquifer system in the U.S. Within this subterranean maze, “fossil water” is banked at depths up to 2.5 miles below the earth’s surface through an endless maze of Paleozoic carbonate rock formations, chambers and networks that are connected by a series of fractures, fissures and fault systems that can impede, enhance and store groundwater flows. The actual depth of Devils Hole itself is still not known; USGS divers Alan Riggs and Paul DeLoach with the late renowned cave diver Sheck Exley reached 436 feet in 1991, stating that they could see an additional 150 feet before they lost sight as the chamber curved sharply downwards.

The 12,000-foot Spring Mountains range, located to the east and southeast of Ash Meadows, along with the Pahranagat, Sheep and other smaller eastern ranges, are the primary high-elevation source for groundwater discharged in the region. Amazingly, the water bubbling up from the subterranean depths is estimated to have resulted from precipitation and snow that fell on these mountains during the late Pleistocene—well over 10,000 years ago. As this water ever so slowly filters down into the carbonate rock aquifer, it becomes increasingly alkaline over time. Flowing southwesterly and circuitously under the irrevocably damaged lands of the Nevada Test Site (NTS)—now known as the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS)—the water is forced up to the light of day when it encounters the Gravity Fault that blocks its path further west.

There’s an underground ocean under the Test Site…if they keep messing around in there, they’ll murder the land they’re living on by ruining the water. Water is life. —Unnamed Western Shoshone consultant, quoted for a 1991 Nevada State report on the proposed Yucca Mountain Nuclear Repository.[15]

The ancient alkaline waters contained within this interrelated hydrological system are pushed upward into the desert along fault lines at select geographical points, engendering a series of beautifully fragile springs and seeps. Some, such as Ash Meadows, produce continuous flows at 10,000 gallons per minute. Spring complexes such as these, although somewhat rare, are found across the vast 17,400-square-mile Death Valley Regional Groundwater Flow System region. This is a hydrological network of interconnected aquifers of varying geological composition, including carbonate, volcanic and valley fill covering large portions of both southeastern California and southwestern Nevada. The area hosts the former NTS and Death Valley National Park (DVNP)—both federally funded institutions with contrasting, and often drastically conflicting, operational agendas.

Technically, the Death Valley Regional Groundwater Flow System is a three-dimensional transient groundwater flow model of the larger Death Valley region, developed by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) in response to concerns of potential health hazards resulting from the intensive underground nuclear weaponry testing conducted historically at various sites in the NTS both above and below the regional water table. These activities have produced prolific amounts of toxic radioactive and chemical contaminants—some of which are known to persist within the environment for tens of thousands of years. In the “high transmissivity zone” of Frenchman Flat alone, it is estimated that 90,000 acre-feet of water lies beneath this traumatized and pitted landscape used for nuclear weaponry testing between 1951-1992.[16] With the region’s rapid and surging population growth and the need for new groundwater sources, the DOE and federal government found it necessary to determine the groundwater flow patterns to evaluate the risks and possible long-term effects of contamination within the surrounding region. The 2010 study, which took over more than ten years to develop was, in part, driven by the effort to site a high-level nuclear waste repository deep within Yucca Mountain, located directly north of Ash Meadows. In a weird twist of fate—because the DOE contaminated this prized groundwater so thoroughly—their actions may end up serving to preserve it for the future generations along with the regional spring complexes dependent on it, regardless of the corrupted state it is in today.

To illustrate the interconnectivity of the Death Valley Regional Groundwater Flow System as well as its connectivity to the rest of the planet, one should consider the rare occurrences of remote seismic events that jolt the otherwise placid waters of Devils Hole. On March 20, 2012, several field biologists conducting research within the cavern witnessed one such event firsthand, catching an “underground tsunami” on video just after 11 a.m. These events occur when distant seismic waves that are normally undetectable by humans are amplified through the massive aquifer as water is forced up into the small chamber of the fissure, releasing intensified energy capable of generating tidal surges of up to four feet high. The captured video shows the pool’s water, pupfish and algae mats as they are sucked down into the chasm repeatedly until several minutes later the water levels returned to normal. The earthquake—a 7.4 magnitude temblor originating in Oaxaca, Mexico, centered twelve miles below the earth’s surface and some 2,000 miles away was the cause of this chaotic incident.[17] This was not the first or last time this type of seismic event would occur here, suggesting that complex interrelated geological machinations deep at work within the earth’s crust are connected to far distant geographical points and are more complicated than we can ever imagine.

Closer to home, but far more disturbing, are the results of a recent study conducted by researchers at Brigham Young University, published in the Journal of Hydrology in 2010, confirming earlier suspicions that “water arriving at Ash Meadows is completing a 15,000-year journey, flowing slowly underground from what is now the Nevada Test Site.”[18] Although scientists presume that it will take an additional 15,000 years for the NTS radionuclide-laden waters to reach Devils Hole and other interconnected spring complexes, it is extremely disconcerting from a mindful perspective that our past actions will wreak havoc for our descendants and the rest of the living creatures and plant life well into the future.

The Indigenous peoples of the region—the Western Shoshone, Timbisha and Southern Paiute—always knew and respected this great underground aqueous resource. Consider that one of the most common morphemes used in the Western Shoshone and Southern Paiute languages is paa (pa- “water”). “Paiute” directly translates as “people of the water.” Indeed, both tribes, through ancient oral traditions and songs, share a mythographic or memory map of the landscape that positioned key springs and other water resources throughout the area included within the Death Valley Regional Groundwater Flow System—now largely forbidden and inaccessible to them in areas now controlled by federal government agencies such as the NTS, Nellis Air Force Range and DVNP.[19]

Shamans and medicine people of the region who serve as intermediaries between tribal members and the “larger ecological field” are said to travel, albeit at their own personal risk, between spring complexes through these underground waterways that require unique powers to access. For the various tribal groups historically centered here, water is largely considered the primary healing force; when it or the places it emanates from are under stress, contaminated or destroyed, it directly affects the well-being of all things equally —humans, plants, animals, rocks—because indigenous people see the nonhuman natural world through what author Valerie Kuletz refers to as an intersubjective relationship, in which “the natural world is perceived as possessing a level of subjectivity that Euro-Americans usually grant only to other humans.”[20] She goes on to state, “Indian people clearly see themselves non-dualistically as both part of and distinct from the natural environment.”[21] Indian elders have commented on how distressed they are when they are unable to fulfill their “contracts with nature” or collective responsibility to steward the land and receive its gifts in return throughout areas now off-limits to them—including the NNSS or most of DVNP.

Although I’d personally not associate the magical Devils Hole with Charles Manson, it is interesting to note that he spent several days here scheming a way to enter the chasm. It seems that Manson had an ongoing obsession to locate Death Valley’s “portal to the underworld,” where he and his Family adherents could wait out the coming apocalypse set in motion by their “race war.” The problem was that he’d need to figure out a way to drain it. As several websites suggest, Manson may have been spurred by an alleged Indian legend that surfaced during the 1920s, contending that a subterranean sect of leather-clad humanoids lived down within an eerily yellow-green lit abode somewhere in the Mojave Desert.

Continue reading this dispatch in Divining Devils Hole Part II.

The author thanks Kevin Wilson, ecologist and manager of the National Park Service Devils Hole program for graciously providing feedback for this dispatch. Special thanks for Jim Houtz for sharing his diving stories and scrapbook for this dispatch. The photograph of the diver was taken in April 2015 by Brett Seymour (NPS) and provided courtesy of the National Park Service. Sound design provided by Tim Halbur. This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] Leroy & Jean Johnson, Escape from Death Valley (Reno and Las Vegas: University of Nevada Press, 1987), 160. I find it interesting that even with all of the follies present during their difficult crossing, Nusbaumer still found time to appreciate some of the region’s more unusual geological offerings.

[2] Alan C. Riggs and James E. Deacon, “Connectivity in Desert Aquatic Ecosystems: The Devils Hole Story,” Conference Proceedings, Spring-fed Wetlands: Important Scientific and Cultural Resources of the Intermountain Region (2002): 3.

[3] Riggs and Deacon, “Connectivity in Desert Aquatic Ecosystems,” 3. This paper incorrectly attributes this statement from Barbara Durham, a Timbisha Tribal Elder. During an oral interview conducted by the author at the Timbisha Village in Death Valley National Park on October 20, 2015, Ms. Durham said that she did not personally play or swim in Devils Hole as a child, as this paper incorrectly states. Rather, she said that this particular story was told to her by other tribal elders.

[4] Steven R. Beissinger, “Digging the pupfish out of its hole: risk analyses to guide harvest of Devils Hole pupfish for captive breeding,” PeerJ 2:e549 (September 9, 2014).

[5] Christopher J. Norment, Relicts of a Beautiful Sea: Survival, Extinction, and Conservation in a Desert World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 124.

[6] C. nevadensis Shoshone was considered extinct by the late 1960s but “rediscovered” in 1986. Cyprinodon nevadensis calidae, the Tecopa pupfish, was declared extinct in 1981.

[7] Riggs and Deacon, “Connectivity in Desert Aquatic Ecosystems,” 15.

[8] Christie Wilcox, “The Unexceptional Devil’s Hole Pupfish,” Science Sushi, Discover Magazine, September 30, 2014.

[9] Noted in correspondence with the author by Kevin Wilson, ecologist and manager of the National Park Service Devils Hole program, August 2015.

[10] Norment, Relicts of a Beautiful Sea, “…I imagine that there would have been ceremonial prayers, perhaps a mythical nod toward the “water babies” said to lurk in Devils Hole….” 124.

[11] Wilcox, “The Unexceptional Devil’s Hole Pupfish.”

[12] Riggs and Deacon, “Connectivity in Desert Aquatic Ecosystems,” 11-12.

[13] “Devils Hole, Nevada—A Primer,” USGS, https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2012/3021.

[14] Riggs and Deacon, “Connectivity in Desert Aquatic Ecosystems,” 1.

[15] Unnamed Western Shoshone consultant quoted in Catherine S. Fowler, “Native Americans and Yucca Mountain,” Volume I, Cultural Resource Consultants, Ltd., Reno, NV, October 1991. 102.

[16] Norment, Relicts of a Beautiful Sea, 187.

[17] Peter Bryne, “Pupfish, Downfish: Subterranean Tsunami Gives Vertical Shakes to the Water-Hole Home of Endangered Fishes,” Scientific American, March 27, 2012.

[18] Joe Hatfield, “Oasis near Death Valley fed by ancient aquifer under Nevada Test Site, study shows,” BYU News, June 1, 2010, https://news.byu.edu/news/oasis-near-death-valley-fed-ancient-aquifer-under-nevada-test-site-study-shows.

[19] For further reading see: Valerie L. Kuletz, The Tainted Desert: Environmental and Social Ruin in the American West (New York: Routledge, 1998).

[20] Kuletz, The Tainted Desert, 207.

[21] Kuletz, The Tainted Desert, 193.