Gold is elusive stuff. In fact, so elusive that its earthly genesis had remained a mystery until August 2017, when astrophysicists officially determined what many had already theorized: Gold forms in our universe during the aftermath of neutron star collisions. Within the atomic furnace of these rare events, heavy r-process elements are forged, including gold and platinum, from highly condensed matter weighing in at ten million tons per teaspoon. Production of r-process elements occurs within seconds of a neutron star’s final death throes. Immediately these r-process elements are cast into the cosmos along with dust and gas. Later they are reassembled within the core and mantle of planets such as ours. Without question, this process is exceptionally infrequent, extraordinary and magical.

With the pandemonium gold has caused throughout time, it may come as a surprise for the reader that this celebrated metallic element is sought primarily for vanity—about half the gold mined historically and presently is fashioned into jewelry. Another 40 percent is hoarded for wealth. Only ten percent is used for industrial purposes.[1] It is estimated that 166,000 metric tons of gold have been mined throughout human history. Today, the largest consumer of gold is India. The golden bridal dowry—a practice outlawed in the country since 1961—continues to be customary for traditional weddings. Regardless, the United States remains the world’s largest holder of gold reserves.

Discovery and attainment of gold are inextricably tied to the expansion of the American West—most significantly within California—which lists gold (Au) as its official state mineral. Hence, California’s relationship with gold is both complicated and intimate. Nevada and Arizona have additionally had their share of bedeviled bouts with the stuff, although the Silver State is more famous for its Comstock Lode.

Exploration of the Mojave Desert was driven by the desire to locate gold—the Spanish began actively mining gold in Alta California as early as 1775 at the Potholes, near Yuma, Arizona. After Mexican Independence in 1821, location and extraction of gold remained a priority. Still, it was gold’s “rediscovery” on January 24, 1848, at Sutter’s Mill that would compel some 300,000 individuals over the next five years to heedlessly travel over land and sea—driven by their heady dreams of “striking it rich.” One infamous group of intransigent, ill-fated immigrants would endure crossing the harsh desert homeland of the Timbisha Shoshone during its 1849 quest to obtain gold further west. Little did they know that the surrounding desert—now known as Death Valley—would eventually host its roster of gold-driven booms and busts.

Those hell-bent in their pursuit of gold would bring about enduring cultural transformations and irreversible environmental legacies within California and other western states. For a lucky few, the procurement of gold provided prosperity and the possibility of reinvention. California’s former librarian Dr. Kevin Starr stated, “The discovery of gold and the Gold Rush of 1849 are internationally recognized events that changed the course of history. Not only did the Gold Rush give California its strong economic foundation, it created unprecedented cultural diversity as people from all corners of the world came in search of fortune. Then, as now, California represented enchantment, diversity, innovation and leadership to the rest of the world.” From the mid-nineteenth century through the 1970s, California would produce over a million ounces of gold, representing 35 percent of all gold produced during this span in the U.S.[2]

The earliest recorded discovery of gold in the Mojave Desert region by non-Indigenous people occurred during the mid-1820s at Rio Salitroso (or Salt Spring) along the Spanish Trail, just south of the Dumont Dunes near the southern end of Death Valley.[3] Mexican horse traders, along with their nemeses, the horse-thieving Las Chaguanosos—were said to have first panned for gold here while moving stock to and from Southern California and Santa Fe, New Mexico.[4] Towards the end of the 1850s, when Sierra Nevada’s placer pickings (gold nuggets easily accessible in sand, gravel, or on the land’s surface) began to dwindle, exploratory parties of determinedly driven souls traveled east and southward into the state’s arid nether regions lured by the purported legendary riches of the Gunsight, Breyfogle, Pegleg and other mythical “lost” mines.

Gold would be sought and located throughout the Mojave Desert. The most significant discoveries occurred during the sixty-year period after the 1848 Mother Lode strike. The earliest desert prospectors and miners would toil alone or together in small groups at remote, hardscrabble camps, relying primarily on dry-wash methods aided by pickaxe, shovel, sledgehammer, rocker, riffle box and a hand-cranked windlass in their effort to glean riches from the rubble.

Several miners toiling 125 ft below in the Bagdad Mine, Ludlow, CA. Photographed by Charles C. Pierce in 1910. Image courtesy Huntington Library Collection.

Once located, gold-bearing ore could be primitively milled on-site using a burro- or mule-drawn arrastra or, later, with a small steam-powered stamp mill. When available, mercury sourced from cinnabar was used to “attract” and dissolve the gold, creating a crude gray alloy or amalgam.[5] Gold was recovered by heating the amalgam at a high temperature in a retort, furnace or even a shovel held over an open fire until the mercury vaporized, resulting in a “sponge of gold” that would be further processed to form bars for transport. Locally collected wood and charcoal produced in beautifully constructed stone beehive-shaped kilns such as those found at Wildrose Canyon in the Panamint Range fueled large-scale smelting. Some forested areas in higher desert elevations were so completely exploited for this purpose, along with mine timbering and other construction, that some of these areas have remained treeless to this day.

By the end of the nineteenth century, sizeable mechanized stamp mill operations with 100 stamps or more would pulverize ore around the clock. This finely rendered material was deposited onto mercury-coated copper plates that chemically bonded with the gold. The plates were then roasted, thus releasing the gold. However, the mercury process could only recover about 60 percent of the metal. Although the cyanidation process would begin to replace the use of toxic mercury for gold recovery during the 1890s, the amalgamation method remained in continual use through the 1960s—until it was banned for such purposes through the 1976 Toxic Substances Control Act.[6], [7]

Other technological innovations would shift placer and hard rock or underground mining from a largely individualized pursuit to a heavily capitalized and corporatized industry. For example, dynamite, developed by Alfred Nobel, would replace black powder for blasting and come into widespread use by the 1890s. Compressed air for driving tools and machinery, along with carbide lamps, powered hoists, tramways and the invention of the pneumatic drill or “widowmaker” (due to the copious amounts of toxic silica-laden dust the drill produced) were some of the many innovations that industrialized mining practices over the mid-to-late-nineteenth century.

With the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1883, along with subsequent railway lines connecting major extraction shipping hubs of Mojave, Barstow and Needles, the formerly “inhospitable” desert regions were now open for the transport of people, supplies and raw materials. In addition, the construction of the rail lines allowed larger, more technically efficient mining operations to proliferate throughout the region with the settlements that supported them.

Many Mojave mining camps were short-lived despite this improved access. The majority were abandoned within a historical heartbeat. The biggest threats to these burgeoning boomtowns were capricious prospectors, miners and capitalists—opportunists ready to bail ship at the drop of a hat when news of a spectacular claim staked elsewhere had reached them. Over time, this scenario would play out in Ballarat, Calico, Cerro Gordo, Chloride, Dale, Darwin, Goldfield, Harrisburg, Hart, Hornsilver, Lida, Oatman, Panamint City, Rhyolite, Skidoo, Searchlight, Tonopah, Tule Canyon, Vanderbilt and many other camps.

One mining camp to survive, albeit transformed, is Randsburg, California, initially established in April 1895. The camp’s founders included Brooklyn journalist Frederick Mooers, who had traveled to this remote northwestern edge of the Mojave to write a story on dying mining camps but caught gold fever instead,[8] Charles Burcham, a butcher by trade and part-time prospector financed by his wife, Dr. Rose Burcham[9] and John Singleton, a carpenter with little prospecting experience. Mooers had previously prospected the area, but his explorations had yielded nothing worthwhile to mine. Still, he had a hunch. Determined to revisit the region, he secured his partners, mentioned above, along with supplies and equipment. The group set out for the soon-to-be-named Rand Mountains.

The greenhorn Singleton would be the first to stumble upon the protruding rock outcrop that sealed The Rand’s fate.[10] This “cabbage-sized” specimen was said to assay for $950 in Los Angeles—equivalent to about $28,000 in today’s dollars.[11] Mooers, Burcham and Singleton kept their bonanza under wraps for nearly a year as they located, staked and recorded additional claims, including one that would become the Yellow Aster Mine, named after a pulp novel. The mine would soon become the crown jewel of The Rand.

Once the word got out, all hell broke loose. A stampede ensued. People of all backgrounds and professions across the country stormed into the area. By October 1896, prospectors filed 800 claims and by February of 1897, the number had exploded to 4,300, although only 500 were officially recorded.[12] Reports stated that by spring of 1897, over 5,000 newcomers had arrived, although no official census was taken that year.[13]

By 1898, at least fifty mines would be operational including the Baltic, Big Dyke, Butte Lode, Consolidated, Gold Coin, Hard Cash, Kenyon, King Solomon, Little Butte, Minnehaha, Monkey Wrench, Olympus, One-Two-Three, St. Elmo, Wedge, Yellow Aster and Yucca Tree, among others. Ore was shipped and processed at the nearby Garlock mill until 1898, when it was then freighted to Barstow. The Yellow Aster’s owners would build their thirty-stamp mill in 1899 and, two years later, a 100-stamp mill, thus processing ore on site.

Like many of the West’s bustling mining towns, Randsburg’s rapid growth was not exaggerated. “Rag houses,” constructed of canvas and wood, popped up overnight, punctuating the scrubby hillsides. Although lumber was scarce, more permanent wooden buildings soon followed. With no time for remodeling, some rag houses were simply entombed within walls while business continued as usual. One enterprising hotel temporarily lodged its guests with no roof during construction. Workers blasted an unmovable boulder to lay a floor, with no damage to the existing structure. Private entrepreneurs shipped water from twelve miles away in Garlock. End users paid dearly for this convenience.

Rand, and later, Butte Avenues evolved into the central hubs of social life. By spring of 1897, fifty buildings had been erected, including an opera house and twenty-four saloons, with the Elite, Oriole, White Fawn and the Steam Beer Club considered the most exclusive. With the saloons and gambling dens came dance halls and brothels, providing income for the 250 “sporting women” frequenting them. A handful of these ladies—Mexican Nell, Big Ella and French Marguerite—owned and operated their establishments. Saloons and dance halls were required by law to be discreetly separated, so ingenious proprietors built them as adjacent structures, sometimes adding a walkway between them.

Lou V. Chapin, a gutsy female correspondent for the Los Angeles Times traveling alone on assignment vividly and rather wickedly describes The Rand’s nightlife at its decadent height in 1897.

A photographic view of one of the gambling halls would furnish a representation of the various types of the region. There is the rough miner just in from the outlying camp, dressed in blouse, overalls, and hob-nailed shoes, explaining with drunken gravity some “proposition” to one of his kind, who, equally maudlin, is talking at the same time, neither heeding what the other is saying. Tilted back on a chair against the wall is a prospector “down on his luck,” fast asleep under the combined influence of his potations and the heat of the stove. The mining expert, the capitalist, the tenderfoot all are here “picking up pointers,” and sprinkled about are the flotsam and jetsam of humanity that naturally drifts to a mining camp. Crowds of men stand about “talking ore” and interlarding their conversations with profanity. Half way down the hall a sodden-face boy saws away at a fiddle with the expression of a sleep-walker, and by his side a murderous-looking Mexican toys with a guitar. If they make any sound it is audible only a few feet away, so great is the general hubbub. At many of the tables professional gamblers, cool, calm and silent, handle the chips; and roulette, faro and every other known game of chance is in full swing. From its platform in the rear of the hall comes now and then the notes of a piano, played by a muscular, black-eyed woman with puffy eyelids and unnatural complexion, and then a bedizened creature, with a voice like a fish-wife’s, leers at her audience and sings some concert-hall ditty which they appreciate and greet with more or less enthusiastic applause. She comes down and moves among the men, drinking and exchanging ribald jests. The barkeeper, with his sleeves rolled up above his elbows, serves liquid refreshments, and day and night these places are never closed, although they are seen at their busiest from nightfall till daylight.[14]

Chapin would go on to describe a barefooted and bearded wizard, who in all of his “sockless majesty,” divined for gold, silver, water, gas, or oil for $20 down—equivalent to $500 in today’s dollars. The bellicose wizard insisted to Chapin how he had “located” fifty claims, but none paid out as promised. When the author suggested that he’d be better off locating mines for his benefit, he declared that “his love for mankind so great that he would rather be its benefactor than the owner of the wealth.”

By the end of 1898, two major fires, occurring less than four months apart, destroyed Randsburg’s main business district along with the high life it sustained.[15] Town conservatives insisted that establishments of ill repute were the root cause of the fires and grossly underplayed the fact that the region’s arid climate had dried the settlement’s wooden structures to mere kindling. Others, such as the Order of Citizens of Randsburg, posted flyers in November of 1898 commanding, “All ex-convicts, masquereaus, disreputable loafers without visible means of support and bad characters are hereby ordered to leave Randsburg forthwith.” Paranoia ensued, and more threats to publicly whip or even lynch those suspected of arson were posted. However, the fires turned out to be the least of the town fathers’ concerns. Two years later, after multiple strikes of silver and gold were discovered across the state line in Nevada, the once-robust population of The Rand quickly dwindled.

The Yellow Aster Mine would continue to operate until 1942 when President Roosevelt executed Limitation Order L-208 banning the extraction of non-strategic metals, including gold, during World War II. Nevertheless, between 1895 and 1939, more than 3,400,000 tons of ore had been milled here, yielding 500,000 ounces of gold.[16] The mine would remain dormant until the 1980s when contemporary heap leach extraction methods using cyanide became widely used for industrial-scale gold mining. Nearby, Osdick (now named Red Mountain) and Atolia would later spawn profitable mines of silver and tungsten, essential for steel manufacturing during the 1940s, which kept the area actively mining over most of the twentieth century.

After Jim Butler discovered a spectacular strike on May 19, 1900, in a remote central Nevada location that would soon become Tonopah—hordes of miners, prospectors, speculators, capitalists, shopkeepers and other opportunists hurriedly set off for the Silver State, launching a migratory event the West had not witnessed since the discovery of the Comstock Lode in 1859. Tonopah lies just outside the Mojave Desert’s geographical purview, within the Great Basin—but the mining camp and the city it evolved into remained a vital mining hub of the region for most of the twentieth century.

Between 1901 and 1910, Tonopah would mature into a modernized, electrified city boasting between 5,000 and 10,000 people from diverse ethnic backgrounds and countries of origin, including African Americans, Native Americans, Chinese, Cornish, Italians and Slavs. Although ore production had reached its peak by 1920, Tonopah’s mines would continue to produce over the next forty years, yielding a total gross between 1901 and 1941 of nearly $148 million17—even while the silica-laden “death dust” found to be so prevalent in Tonopah’s underground mines was causing miners to drop like flies from silicosis.[18]

Just as Tonopah began to prosper, treasure seekers were busying themselves twenty-seven miles to the south, where the Great Basin begins its transition into the northern Mojave Desert. Then, at a dormant volcanic site punctuated with Joshua Trees ignored by previous prospectors, news circulated about a monumental strike discovered in December 1902 that would completely blindside Tonopah.

Although renowned Shoshone prospector Tom Fisherman deserves credit for the mine’s actual discovery, a handsome Tonopah roustabout named Harry Stimler (himself half Shoshone)—along with his childhood friend and partner William Marsh—received the public acclaim for staking it.[19] As it turns out, Stimler and Marsh, both in their early twenties, had discreetly followed Fisherman from Tonopah, during a sandstorm, to his camp where they would stake several claims at the exact location that Fisherman had been working. There were rumors that the two men had strong-armed Fisherman into submission, but it is more likely that familial ties between Stimler and Fisherman aided them in obtaining access.[20] In any case, these claims would later prove highly profitable. The duo had the nerve to name their first producing mine “Grandpa,” poking fun at the proud boosters of Tonopah.[21]

Fisherman, considered by historian Sally Zanjani to be “the most gifted prospector Nevada ever produced, perhaps the finest in the West,” would reap no great wealth from his numerous discoveries. Nevertheless, he managed to stay in the game by occasionally stringing along gullible greenhorns that he had lured into “grubstaking” or funding him—promising a portion or even half of the strike’s profit if he indeed discovered one. Many disingenuous white prospectors practiced this tactic, the most infamous being Death Valley Scotty, a.k.a. Walter E. Scott. Over the years, Scott peddled an elaborate promotional scam that ultimately financed the construction and opulent furnishings for Scotty’s Castle in Death Valley.[22] Stilmer and Marsh, themselves greenhorns relatively unskilled in the business of mining, had, in the end, let the fortune slip right through their hands.

Like other antecedent gold strikes, Goldfield would boom quickly, yielding magnificent wealth within two short years. Over time, its mines would generate 30 percent of Nevada’s overall gold yield. To comprehend the immense value of Goldfield’s ore, consider that Tonopah’s silver to gold ratio was about eighty-six to one. Compare that figure to Goldfield’s three-to-one gold to silver ratio.[23] Indeed, Goldfield’s ore was so rich that it didn’t require milling, so it was shipped directly to a smelter in Oakland, California, without prior processing. But, like an evanescent Fourth of July sparkler, Goldfield shined ever so briefly. At its peak in 1906, the settlement had attracted some 18,000 to 20,000 individuals, but by 1910, the headcount would precipitously drop to 5,400 souls. During its brief run, notable Western personalities, including Wyatt Earp and his doomed brother Virgil, would reside here. Unfortunately, not long after they arrived in 1905, Virgil caught pneumonia. After six months, at age sixty-two, he succumbed during one of the deadly influenza epidemics that raged through the city from 1904 through 1907.

While Goldfield’s party lasted, modern and archaic culture collided at this twentieth-century crossroads. Under Main Street’s crisscrossed canopy of Edison incandescent bulbs, newly arrived automobiles and motorbikes markedly stood out against the backdrop of dusty packed burros and horse-drawn wagons. Goldfield’s freshly-monied residents would flagrantly partake in a wanton subculture brimming with airs of sophistication and unbridled decadence. Bartenders of the Northern Saloon, one of forty-nine operating in 1907, served up 500 gallons of whiskey daily from their sixty-foot bar.[24] Five hundred women were said to work at Goldfield’s numerous red-light district saloons, brothels and cribs. The more adventurous nightcrawlers could saunter down to Hop Fiends’ Gulch to satiate themselves at fourteen smoke-filled opium dens where prominent Goldfielders often slummed shoulder-to-shoulder alongside the town’s more down and out citizenry.

Greed would inflame discord when Goldfield Consolidated Mining Company bosses George Wingfield, a former gambler and faro dealer, and soon-to-be-elected U.S. Senator George Nixon,[25] launched their war on “high grading.” A common practice where miners and mill workers pocketed prime chunks of ore in clothing, headgear, lunch buckets and even their most private orifices. The pilfered ore was traded on the black market at half the ore’s normally assayed value. An enterprising high grader could pocket up to $1,800 worth of ore during a single mining shift.[26] The miners rationalized the practice because of poor pay (on average, miners were paid $4.50 a day for backbreaking labor). Still, the angry syndicate bosses claimed that high grading cost them at least 40 percent of their profit. This robust black market economy likely supported the legitimate businesses of Goldfield because the practice was so widespread. The syndicate hired professional goons headed by the energetic Constable Inman, who were paid $10,000 a month plus a 40 percent cut of any stolen high-grade ore recovered to combat the pilfering.[27]

As the high-grading controversy intensified, labor tensions rose. Wingfield and Nixon would instigate a successful union breakup of the Western Federation of Miners and the Industrial Workers of the World through the support and intervention of federal troops when strikes broke out between 1906 and 1908. Over the long term, Wingfield and Nixon’s suppression of the unions ensured that “mining camp ideology” that promoted rugged individualism over community values would continue to influence and shape Nevada’s political landscape for years to come. Goldfield’s production would soon climax by 1910. While remarkably rich, the deposit had proven to be limited. By 1912, Goldfield was spent. Folks were moving on.

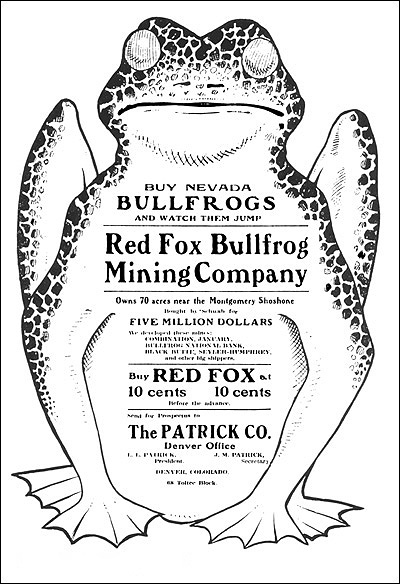

“Buy Nevada Bullfrogs and Watch Them Jump,” Mining Investor, February 1906.

The region’s last great boom and bust would occur about sixty-five miles south of Goldfield near “Old Man” Beatty’s ranch along the Amargosa River. Named after a squat piece of greenish-turquoise quartz ore riddled with free gold, the original Bullfrog Mine was discovered on August 9, 1904, by Frank “Shorty” Harris and his prospecting partner of the moment, Ernest “Ed” Cross. Once their strike became public, Goldfielders, along with those further afield, hastened across the desert packing supplies on whatever mode of transportation they could muster—whether it be a motorized jalopy, an overpriced $500 jackass or a wheelbarrow.[28] Harris would promptly squander his share of the claim for a measly $1,000 during a six-day drinking binge at Goldfield’s saloons. Cross, a young, sober newlywed, would hold onto his half, eventually selling it for a reported $125,000—after forming a stock company with the grifter that had taken advantage of Harris in his inebriated state.[29] Harris would recount an alternative version of the story, when interviewed by Philip Johnston for an October 1930 Touring Topics feature, stating he received $25,000 from a signed bill of sale after being locked in a room for six days with an unlimited supply of whiskey by a man named “Bryan.”

When the stampede petered out three weeks later, over 2,000 claims had been recorded within the newly organized, thirty-square-mile Bullfrog Mining District. Its premier settlement, Rhyolite, was named after the region’s rosy-colored, silica-rich felsic extrusive rock. So when the newly platted town’s population doubled from 1,200 to 2,500 by June 1905, it appeared that development was officially on overdrive.

By 1907, Rhyolite’s population had again doubled to 4,000-plus citizens.[30] The town boasted power, water, telegraph and telephone lines. A mill processed up to 300 tons of ore a day. Three railroads, several newspapers, a stock exchange, post office, schoolhouse, hospital, opera house, police and fire departments, shops, churches, saloons, plus a thriving red-light district created a cosmopolitan atmosphere. The John S. Cook & Co. Bank, a three-story concrete, steel and glass building, was richly appointed. But, by far, the structure most unique was the bottle house built during February 1906 by miner Tom T. Kelley with 50,000 beer and liquor bottles—artifacts attesting to the giddy frantic rush that occurred just a few years earlier.[31]

Clever nationally advertised promotional campaigns displaying bullfrog illustrations with catchy slogans such as “BUY NEVADA BULLFROGS AND WATCH THEM JUMP” tempted investors, including the likes of steel magnate Charles Schwab, to drop millions into the district’s mining stocks. Schwab would purchase Bullfrog’s most famous producer, the Montgomery Shoshone Mine, from Bob Montgomery for over $2 million.[32] The mine had been located for Montgomery by another Indian prospector named Shoshone Johnny.[33] Still, this celebrated mine would not shed a cent to any for its stockholders except Schwab.

Rhyolite’s growth would implode just as fast as it had exploded. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and ensuing fire, along with other unexpected events, would divert capital away from the region’s highly speculative mining investment opportunities during San Francisco’s rebuilding process. When the fall Panic of 1907 hit, investors dropped out forcing many regional banks and businesses to close. As the dominos fell, Rhyolite’s major mines would shut down, sending residents fleeing—leaving the once-promising camp to atrophy. By 1910, the census taker listed only 611 residents.[34] When the mighty Montgomery Shoshone finally stopped production in 1913, the coffin was nailed shut. [35] By 1920, only fourteen residents remained. Many of the town’s wooden buildings were cannibalized for materials or moved to Beatty and beyond. The Cook bank building and other concrete and stone structures cracked and crumbled over time, allowing the desert to reclaim the plots where they had once stood, seemingly impervious to the desert elements.

Looking back at the highs and lows of the Mojave’s turn-of-the-century extraction heyday, it is easy to get caught up in the perceived romance of the era. However, in Patricia Nelson Limerick’s 1992 essay, Haunted by Rhyolite: Learning from the Landscape of Failure, the author counters the nostalgic perspective of many western writers who continue to idealize these social and economic follies in a glut of regional ghost town guidebooks.[36] Mark Klett’s quietly desolate large format black and white photographs, showing what remains of these once lavish structures, compliment Limerick’s compelling discussion of the “cult of ruins” that so enraptures these authors.

Considering her story as a parable, as the essay’s title suggests, Limerick comments, “expansion, construction and growth are certainly part of the region’s history, but so are contraction, retreat and abandonment. Fixated on expansion, historians have been blinded to the many episodes of retreat… Fixated on growth, they’ve had little attention left for shrinkage, abandonment and waste—or, for that matter, that most elusive state of all, stability.”

Still, idealized ghost town tourism is alive and well today in the Mojave Desert at Disneyfied places like Calico, California and Oatman, Arizona, which equally boast reconstructions of mining boomtown life. Calico, located just east of Barstow, California is a silver mining town founded in 1881 that had been purchased and restored by Walter Knott, founder of Knott’s Berry Farm, in 1951. The site is now managed by San Bernardino County Regional Parks and is a California state historical landmark. Attractions include a restored main boardwalk with museums, shops, eateries, saloons plus a plethora of cheap souvenir shops. Visitors can descend 1,000 feet into the old Maggie Mine, ride on the Calico Odessa Railroad or pan for gold.

Oatman, Arizona, is another “tourist trap” replica of a nineteenth-century gold camp, located near Kingman in the Black Mountains of Mohave County, Arizona. Its most popular tourist attraction is the group of wild burros that visit the town every day looking for a handout.

The facade of the Porter building photographed by Kim Stringfellow in August 2018.

The Mojave Desert will be forever associated with the iconic image of the lone prospector treading alongside his scruffy burro through a desolate landscape. Colorful, peripatetic characters including Burro Schmidt, Alice “Happy Days” Diminy, Lillian Malcolm, Panamint Annie, Seldom Seen Slim, plus others fill many an account of Death Valley and the surrounding environs. These roving, rugged prospectors traveled throughout the region between primitive camps and the eventual towns that sprang up just as swiftly as they had fizzled out. Other seekers, including many unnamed Chinese, Mexican, Spanish, African and Native American prospectors and miners, likely explored and worked claims within the larger Mojave Desert and beyond but are poorly represented within the historical record.[37]

By far, Frank “Shorty” Harris is the best-known prospector of the bunch. Spry, loquacious and diminutive, Shorty was the quintessential desert rat. Born to an Irish father and Scotch mother on July 21, 1857, in Providence, Rhode Island, Harris was orphaned by age seven and sent to live with his father’s sister.[38] By age 11, Harris had become a factory mill worker, and by age 14 he would run away from his aunt’s home, thus embarking on a life of restless wanderlust riding the rails. He crisscrossed the country, eventually heading out west while hiding underneath a train carrying President Ulysses S. Grant, landing him in Los Angeles in 1877.[39]

Harris plied his trade while wandering and working odd jobs across Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada and Utah until fate brought him into Death Valley during the late 1880s. At a remote outpost up in the Panamint Range on St. Patrick’s Day of 1892, Harris and his prospecting partner John Lambert (one of many to come) located their first modest gold strike.[40] Not content to mine the claim, Harris sold his share and quickly moved on to the next big thing. Harris thus began his surprising pattern of striking it rich and consequently striking out. But perhaps that wasn’t the point after all—Harris would repeatedly state to curious tourists and biographers during his later years: “The goal is the thing, not the gold.”[41]

Former Inyo County treasurer George Naylor pointed out that Harris put “more towns on the map, and more taxable property on the assessor’s books than any other man, regardless of size.”[42] Indeed, Harris had a good eye for gold.

One of Harris’ more well-known former prospecting partners was Jean Pierre “Pete” Aguereberry, a French Basque who located the Harrisburg strike in the Panamint Range in early July 1905 while traveling with Harris. Aguereberry commented, “He [Harris] was always in a hurry, never looked right or left, just kept prodding and cussing his burro.” Indeed, he would often not stay long enough to see if the strike paid out. Harris was likely miscredited with Aguereberry’s discovery because his larger-than-life persona kept his oft-mentioned name in the headlines of regional mining journals and boomtown newspapers.[43]

Standing barely five feet tall, Harris managed to charm the ladies—undoubtedly aided when the man was flush with a hefty bankroll.[44] He was generous with his colleagues, especially when intoxicated. But a softer side of Harris describes his penchant for caring for the creatures of the desert. A July 1954 Desert Magazine article described how Shorty would regularly set out shallow tubs of water for the wildlife and insects at his remote desert campsites, instructing future visitors: “Water. Keep filled for birds and animals, please.”[45]

Harris would remain a continual presence in the Mojave over the fifty or so years he repeatedly roamed across it. He would spend his final days living in dusty Ballarat with his dog, Sourdough, in a sagging adobe schoolhouse that would eventually cave in on him. Then in his mid-seventies, Harris would barely survive the accident. Understandably, the ordeal had taken a toll on him physically, and he spent several months recuperating. Still, Harris remained game for another big strike and seemed anxious to get out again into the desert.

A year later, on November 10, 1934, Harris would die in his sleep in Big Pine, California, at age 77. He requested that he be buried alongside his friend Jim Dayton, the former borax swamper and caretaker of the Furnace Creek Ranch. Dayton had perished, along with his team of horses, near Bennett’s Well in August 1899. Harris also asked that his grave be marked with this simple epitaph, “Here lies Shorty Harris, a single blanket jackass prospector.” Friends, former prospecting partners, journalists from afar, plus many others would attend his funeral in Death Valley.

Prospecting and mining were not exclusively male endeavors. Although Cornish superstition held that both whistling underground or working alongside women in mines would bring bad luck and prove catastrophic, some would prove noteworthy prospectors and even manage to mine alongside men within subterranean depths.[46] But it appears that only a small number of these women’s lives are recorded within the historical record.[47] Some, such as Belle Butler (the wife of Tonopah’s founder Jim Butler), discovered significant gold strikes in the region. Belle’s instincts for prospecting led her to locate the most lucrative mine at Tonopah—the Mizpah, which she recorded in her name.

Others owned and operated mines throughout the region, including Dr. Rose Burcham, who meticulously managed The Rand’s Yellow Aster mine. Dr. Frances E. Williams was co-lessee of Goldfield’s crown jewel, the Frances-Mohawk. Williams, nicknamed “the steam engine,” had years before made a fortune on a silk-hat varnish concoction but lost her wealth after channeling family assets into an ill-advised Florida orange grove venture that was destroyed by an overnight freeze. Nevertheless, she would transform herself into an “electro-therapist” and a successful mining entrepreneur by middle age, after heading west to California. She eventually landed in Tonopah by 1903 at age 59 but quickly left for Goldfield when gold was discovered there. Upon settlement, the “doctor” quickly acquired 1,200 acres of “rich coal” claims forty miles west of Tonopah. She thus began building her fortune again—this time from gullible Midwestern farmers willing to back her settlement project and “black gold” holdings that turned out to be worthless.

Within three years, Williams had funneled the ill-begotten money into a group of productive Goldfield claims. These included a lease of the Frances-Mohawk with her partner, David Mackenzie. which garnered “$2,275,000 worth of ore from a section of ground 200 by 375 feet.”[48] Her lucky streak would continue for a few more years when she acquired the Royal Flush in Nevada’s Gold Mountain Range, northwest of Death Valley. This mine would give forth ore samples reportedly assaying higher than any other in Goldfield’s history. The discovery supported her ingenious promotional pitch that the Royal Flush was indeed the infamous Lost Breyfogle mine—a brilliant marketing scheme that would-be investors ate up. But in the end, the remarkable assay had proven false—the mine failed to produce by the end of 1909. In March of the same year, a lawsuit ensued, brought on by the mine’s owners, George Wingfield and partners, who sought damages from poorly constructed timber supports and other shady operational practices at the Frances-Mohawk lease. Two days later, after dining in a posh Goldfield restaurant, Williams would return to her hotel room only to collapse and die from a massive heart attack at age 65.

A contemporary of Williams, whom it appears she never met but likely passed once or twice on the boardwalks of Goldfield, was Lillian Malcolm, a former New York stage actress. The latter began her prospecting career at age 30 in 1898 in Yukon’s frozen expanses with no prior experience. After admirably surviving for several years in the Great North but without great success, Malcolm, now penniless, made her way to central Nevada in 1904 with hopes of hitting pay dirt. Unfortunately, she had arrived too late but continued to stay in the game by staking several claims in the Silver Peak Range. By September 1905, Malcolm had made her way over to Rhyolite. She would make her first prospecting trip out to the Panamint Range by fall. In November that same year, Malcolm teamed up with Shorty Harris, embarking on a two-month outing in Death Valley and environs with the now-famous prospector. Later, she would mingle with the charlatan/con man Walter E. Scott and his sidekick, Bill Keys.[49] After this sojourn, she traveled to Mexico and back again to northern Nevada to continue her prospecting odyssey. Unfortunately, Malcolm would fade from public view within fifteen years of starting her spectacular journey. No one knows what became of her.

Author Sally Zanjani, who painstakingly researched the previous two women and many other female miners of the American West in her 1997 A Mine of Her Own, refers to Alice “Happy Days” Diminy as “a sort of female Baron von Munchausen.” She is remembered today as a restless, intelligent eccentric. Born in Bavaria in 1852, the independent and adventuresome Diminy traveled throughout Europe before making her way to New York City. After a short stay there, she headed to Louisiana but would eventually land in San Francisco at age 54—just months before the 1906 Great Earthquake hit. Diminy soon married but immediately left for the Nevada mining camps—without her spouse in tow. Reaching Rhyolite, she set up a small saloon dishing up meals to prospectors and all sorts of human flotsam—likely succumbing to gold fever while serving them her fare. Then, taking a lover, she alighted sixty miles northwest where she and her new male partner had recorded claims at Tule Canyon, located in Nevada’s Lida Mining District. Here, she would learn the art of dry washing and hard labor while managing to pen poetry from time to time. It is rather impressive that she handled all of these activities within one year of arriving on the West Coast.

Although Diminy’s placer prospects in Tule Canyon never paid out as she would have liked, she remained a well-respected, if somewhat odd, mining figure of the area. During later years, Diminy’s formerly positive outlook had clouded and turned peevish—causing her to get caught up in several newsworthy courtroom skirmishes and other public and private quarrels. She would depart her beloved Tule Canyon and travel to urban San Francisco (Diminy was now in her mid-90s) only to be placed in a mental hospital in 1946, where she would sadly die two years later.

The last of these liberated, self-determined women prospectors was Panamint Annie, a striking, half-Iroquois raven-haired beauty, who had made her way out to the Mojave Desert after her mother’s and sister’s untimely deaths resulting from a plane crash. Had she not decided to take a joy ride on a motorcycle that same week, she may have suffered a similar fate—her father’s punishment had kept her from traveling on the ill-fated trip.

Mary Elizabeth White (Annie’s legal name) was born to an army surgeon and his wife on June 22, 1912, in Washington D.C. She would marry at 15 and give birth to two children (one died as an infant). She divorced soon after. Unconventional and rebellious, White began driving bootleg liquor across state lines into Canada and later traveled west via Texas to work as a dude ranch cook in Colorado. Finally, it appears that she made her way to California in hopes of alleviating the scourge of tuberculosis that she had contracted during her teens. Finding the desert country healthful and beneficial, White settled in Shoshone, California, in 1931, where the therapeutic thermal mineral springs helped restore her lungs. Here, she would fall in love with the desert and begin her prospecting journey.

In 1936, White left Shoshone for Colorado to marry a cowboy named Bryant. But, unfortunately, marital bliss was short-lived—while seven months pregnant with her daughter, Doris, her husband died. So, after Doris was born in 1938, White returned to the Amargosa and began venturing into Death Valley proper.

Old-timers gave White her sobriquet in memory of another, earlier, but mostly forgotten Panamint Annie, also from the East Coast. Like her, White would live independently, emancipated from dependence on men. Prospecting out of an outfitted flatbed truck with a canvas tent and cots, she lived off the land. White was quite capable of changing a truck tire or fixing a transmission when necessary. When Doris visited her mother, they dined on a camp-roasted rabbit or snake that Annie had shot. After Death Valley became a national monument in 1933, she and nearly 200 other prospectors and miners were allowed to continue their pursuits and lifestyle under a special permit.

Annie was the only single woman known to be part of the small, subsistence mining community in the Panamints—a common communal lifestyle choice for many male miners. This “family,” with eight to ten men, with whom she remained romantically uninvolved, shared domestic tasks and chores among the group. By her inclination, it appears that she helped with more traditional “woman’s work” around the camp, including washing clothes and cooking meals. Doris confided to Zanjani how Old Man Black, One-Eyed Jack, and other resident miners would lovingly dote on her during her visits to the camp.[50]

Annie would prospect the mountain range for gold, silver, uranium and other valuable minerals. She worked her claims and was said to timber, blast and muck a mine as good as any man. Plus, Annie would bear eight children (four survived) over her life, fathered by different husbands and lovers. Some strikes brought her a small fortune—at least $10,000 in one instance, but it seems that she spent it as fast as she received it on her children’s needs, supplies, repairs, debts and to fund her next prospecting excursion. Then, after breaking her back from a fall at age 45, she began taking the bottle. Drinking binges and gambling became regular habits, but her drunkenness and betting never got in the way of her work or her children’s welfare.

Sally Zanjani states that Panamint Annie “was one of the few women prospectors known to work grubstakes and to receive some of them from other women.” She continues, commenting how Annie had split her $10,000 strike with a woman who owned a grocery store at Death Valley Junction. She had also partnered with Mrs. Frederica Hessler, a Georgia schoolteacher. The latter had inherited the ruins of Rhyolite from her brother.[51] The two of them worked a mine in Rhyolite beginning in 1947, while Annie’s son, Bill, attended school in nearby Beatty. Although Annie lived her life mostly removed from the presence of other women, she never felt competitiveness with her sex but rather, camaraderie.

Panamint Annie was indeed a spirited feminist long before the term existed. While alive, the park service rangers recognized her as a respected prospector/naturalist—whose intuitive knowledge of the National Monument’s geology, flora and fauna was noteworthy and remarkable. Her awareness and insight were garnered through her time alone, while present and focused on everything around her. She had an intimate connection to place, and when slowed with arthritis and finally by cancer, Annie, like Shorty Harris late in life, would too yearn to wander in the desert she so loved. When she died in September 1979, she was buried under a Joshua tree in the Rhyolite cemetery.

All of these female prospectors and mining entrepreneurs, including the numerous women who joined them at mining camps as independent cooks, shopkeepers, dance-hall girls, share in common their desire to exist freely in a place where restrictive social mores and clearly defined gender roles were, for the most part, absent. As a liberated woman, a female prospector could walk the wooden boardwalk of Rhyolite, Goldfield or Skidoo suited in trousers and tall boots without even a second glance—except from one of her kind, who, in prim disgust and barely concealed jealousy, held her feminine skirt aside. But, this social freedom alone does not explain why some of these women persisted in the desert landscape indefinitely.

As Zanjani suggests in her epilogue, when all of the lesser motives had been stripped away, the great love of the wilderness, especially the desert country, was the central impetus that kept these women here. “Prospecting provided a reason for venturing inside it and a means for remaining…[it was] a dream, a mirage of treasure, an addiction, a challenge, an adventure and a quasi-religious experience…when the dreams of bonanza had faded, the love of the land remained.”[52]

This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here. The ruins of Rhyolite, Nevada, photographed by Kim Stringfellow at dawn in August 2018.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] “Gold,” Wikipedia, accessed March 6, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gold. Earthworks.org states that “jewelry represents the equivalent of 70 percent of mine production of gold.” “Retailers: Don’t Let the Mining Industry Tarnish the Jewelry Business,” Earthworks, accessed March 6, 2019, https://earthworks.org/campaigns/no-dirty-gold/retailers.

[2] “California Abandoned Mines: A Report on the Magnitude and Scope of the Issue in the State, Volume I,” Department of Conservation, Office of Mine Reclamation, Abandoned Mine Lands Unit, June 2000, 13.

[3] The Salt Creek Hills Area of Critical Environmental Concern on California State Route 127 near Dumont Dunes features the remains of several early mining workings conducted at this site.

[4] Richard E. Lingenfelter, Death Valley & The Amargosa: A Land of Illusion (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 25. The Las Chaguanosos were an infamous multiracial horse-thief gang composed of New Mexicans, Indians, American and Canadian trappers.

[5] The mercury amalgamation process has been used in gold mining since Roman times. Joseph Nicholson, “How is Mercury Used to Purify Gold?” Sciencing, accessed March 13, 2019, https://sciencing.com/how-mercury-used-purify-gold-4914156.html.

[6] A disturbing trend is the continued use of mercury amalgamation for small-scale artisanal gold mining operations in developing countries. It is considered the easiest and cheapest method for gold recovery. The EPA website states that 20 percent of gold produced worldwide is done through small-scale artisanal gold operations, which are “responsible for the largest releases of mercury to the environment of any sector globally.” For further reading, see “Reducing Mercury Pollution from Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining,” Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), accessed March 13, 2019, https://www.epa.gov/international-cooperation/reducing-mercury-pollution-artisanal-and-small-scale-gold-mining.

[7] The state of California continues to suffer from mercury’s widespread use, especially in areas where large-scale hydraulic mining was practiced, resulting in extensive environmental contamination of river and lake sediments. Mercury bio-accumulates in living tissues as it is passed along the aquatic food chain, poisoning fish, birds and other species, including humans.

[8] W. Storrs Lee, The Great California Deserts (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1963), 160.

[9] Larry Vredenburgh with Gary L. Shunway and Russel Hartil, “Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area,” Desert Planning Staff, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Department of Reclamation (February 1980): 58. Dr. Rose Burcham left her medical practice in Los Angeles to join the group, later becoming Yellow Aster’s chief manager.

[10] Mooers, of South African descent, would name the camp after “The Rand” goldfields of South Africa.

[11] W. Storrs Lee, The Great California Deserts, 160.

[12] W. Storrs Lee, The Great California Deserts, 162.

[13] It appears that many mining boomtown accounts claim a population highpoint of 5,000, so it is difficult to gauge this number accurately.

[14] This excerpt is from “Greed Civilizes the Mojave: Scarlet Women, Horn Spoons, and Wizards,” in True Tales of the Mojave Desert: Talking Rocks to Yucca Man, ed. Peter Wild (Santa Fe: The Center for American Places, 2004), 52-61. Original article: Lou V. Chapin, “A Woman’s Impression of the Randsburg District,” Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1897.

[15] Fire was a recurring threat for every desert boomtown. Nearly all of these settlements experienced at least one major fire during their brief existence.

[16] “Gold Mine Shaft Entrance, Randsburg,” SCVTV, accessed March 6, 2019, https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/lw2370c.htm.

[17] “Tonopah,” ONE (Online Nevada Encyclopedia), accessed March 6, 2019, http://www.onlinenevada.org/articles/tonopah.

[18] Silicosis remained a health issue at the Tonopah mines into the late twentieth century.

[19] Sally Zanjani, Goldfield: The Last Gold Rush on the Western Frontier (Reno: Nevada Publications, 1992), 12. Evidence suggests that Fisherman most likely pointed Jim Butler to his Tonopah strike.

[20] Sally Zanjani, Goldfield, 13-14. In 1907, Fisherman would bring Silver Peak’s Nivloc mine to Harry’s attention so, it is likely that their relationship remained amicable throughout the years.

[21] Fisherman had originally named the mine “Gran Pah” meaning land of much water in the Shoshonean language and Stimler and Marsh retained it. Sally Zanjani, Goldfield, 18.

[22] Sally Zanjani, Goldfield, 296. Many prospectors peddled questionable claims to naïve, unwary would-be investors but Death Valley Scotty seems to take the cake in this regard. For further reading, see footnote 49.

[23] “The History of Goldfield,” The Goldfield Historical Society, accessed March 6, 2019, http://www.goldfieldhistoricalsociety.com/history.html.

[24] Nicholas Clapp, Gold and Silver in the Mojave: Images of the Last Frontier (San Diego: Sunbelt Publications, Inc., 2013), 64.

[25] George Nixon was elected as a Republican to the U.S. Senate in 1905.

[26] Clapp, Gold and Silver in the Mojave, 68.

[27] Clapp, Gold and Silver in the Mojave, 70.

[28] Frank “Shorty” Harris (as told to Philip Johnston), “Half a Century Chasing Rainbows,” Touring Topics, October 1930, 19.

[29] Lingenfelter, Death Valley & The Amargosa, 204. The actual amount of money Harris received for his share of the Bullfrog claim varies significantly from publication to publication. The Lingenfelter text, considered by the author to be the most accurate historical record she researched, is cited here. See the previous footnote for the alternative account.

[30] The population of the greater region, including the towns of Beatty and nearby Gold Center, was said to be 12,000.

[31] The restored house remains to this day a popular tourist attraction.

[32] Lingenfelter, Death Valley & The Amargosa, 20.

[33] Alternatively, he was called Hungry Johnny.

[34] Lingenfelter, Death Valley & The Amargosa, 239.

[35] Montgomery Shoshone Mine is still active. See https://bullfroggold.com.

[36] Patricia Nelson Limerick and Mark Klett, “Haunted by Rhyolite: Learning from the Landscape of Failure,” American Art, Vol. 6, No. 4 (Autumn, 1992): 18-39.

[37] Few accounts of Indigenous prospectors and miners exist in the historical record. Still, many people of all races and nationalities participated in the nineteenth and twentieth-century gold rushes and boomtown culture.

[38] Harris’ grave marker in Death Valley National Park inaccurately states 1856.

[39] Harris, “Half a Century Chasing Rainbows,” 12. President Grant signed the General Mining Act of 1872.

[40] Harris, “Half a Century Chasing Rainbows,” 15.

[41] R.M. Lowe, “Shorty Harris and his Dog,” Desert Magazine, November 1977, 33.

[42] Lowe, “Shorty Harris and his Dog,” 33.

[43] LeRoy and Margaret Bales, “He Belongs to the Panamints,” Desert Magazine, November 1941, 19. Aguereberry is credited with discovering the Harrisburg strike while traveling with Harris to Ballarat on July 4, 1905. The town was initially named “Harrisberry” but was transposed over time to Harrisburg.

[44] Some accounts have Harris measuring 5 feet 4 inches tall, but he was likely closer to 4 feet 10 inches.

[45] Edna Price, “The ‘Other People’ Who Come to the Waterholes,” Desert Magazine, July 1954, 17.

[46] The practice of barring women from employment in mines ended during the 1970s.

[47] The primary source being: Sally Zanjani, A Mine of Her Own: Women Prospectors in the American West, 1850-1950 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997).

[48] Zanjani, A Mine of Her Own, 134.

[49] Zanjani, A Mine of Her Own, 97-99. Many visitors to Joshua Tree National Park familiar with Keys View and Keys Desert Queen Ranch are unfamiliar with Bill Keys’ colorful early prospecting life in Death Valley before leaving for the Morongo Basin to the ranch and starting a ranch family. For further reading, see Lingenfelter’s Death Valley & The Amargosa.

[50] Zanjani states that Doris lived primarily with her aunt in San Bernardino, California.

[51] Zanjani, A Mine of Her Own, 278.

[52] Zanjani, A Mine of Her Own, 316-317.