Eyre’s Quonset hut shop, located in Boron, California, announces itself with a vintage-era-looking sign that simply states ROCKS, and rocks are something that Eyre knows more than just a little about. While conducting solo field reconnaissance for The Mojave Project in the summer of 2014, I spotted the store, Desert Discoveries, from more than a block away. Curious, I proceeded to his establishment anticipating what I would find and, of course, I was not disappointed.

Desert Discoveries is a jumble of rocks, gems, dust, rock cutting and polishing equipment, boxes filled with various mineral specimens collected locally and from afar, uncut gem souvenir flats waiting for tiny specimens to be adhered onto by his younger son (I always wondered who made those things), along with a killer four- and eight-track tape collection and a number of vintage decks for playing them. The walls are papered with faded classic car posters featuring Ed Roth and other hotrod notables. This is a serious rockhounding store, where you can spend a good amount of time exploring while emptying your pocketbook.

A gregarious and easygoing proprietor, David was happy to give me a tour and explain the local mineral treasures he collects from the surrounding public lands and also those he sources through an exclusive contract with nearby Rio Tinto Minerals. The company owns the largest open-pit mine in California, supplying 42 percent or nearly half of the industrial borates in the world that are used as a key ingredient in fiberglass, ceramics, glass, fertilizers, detergents, wood preservatives and many other everyday products. Known by its product name, 20 Mule Team Borax, this same mine, under ownership by the Pacific Coast Borax Company, sponsored the popular radio and television series Death Valley Days from 1952 to 1970. Television hosts included Ronald Reagan (1964–1965), who did the final acting of his career during eight episodes.

Desert Discoveries is the sole supplier of optical-grade Ulexite (NaCaB5O6(OH)6•5(H2O))—a complex boron mineral compound popularly known as “TV rock” for its ability to transmit images of anything it is placed on through its fiber-optic-like naturally twinned parallel fibers. In order to do so, select ulexite specimens are cut and prepared with polished faceplates on opposing ends of the parallel fibers. Finished semitransparent specimens exhibit a silky, vitreous white surface with some gray streaking patterns.

Ulexite forms as mineral-saturated playas evaporate over time. It is often associated or found near veins of borax deposits. Major formations of ulexite are found in the U.S. at Boron as well as Nevada, the Tarapaca Region in Chile and Kazakhstan—specific arid regions that are known to have historically active and prolonged volcanism—but only in Boron is the optical-grade variety found, providing Eyre with a monopoly on its distribution worldwide.

Ulexite was first discovered by and named after Georg Ludwig Ulex (1811-1883), a German chemist who conducted the first chemical analysis of the compound in 1840. It is interesting to note that although ulexite was discovered over 150 years ago it did not inspire pioneering fiber optic technology. Indeed, no one had heard about this unusual compound mineral until after the first fiber optic faceplate had been invented during the 1950s.[1]

Metaphysics crystal healers believe ulexite can “strengthen vision and lessen fatigue” and help balance the third eye chakra promoting creativity and intuition for those who wear gemstones made from this material—however Eyre, will have nothing to do with that.

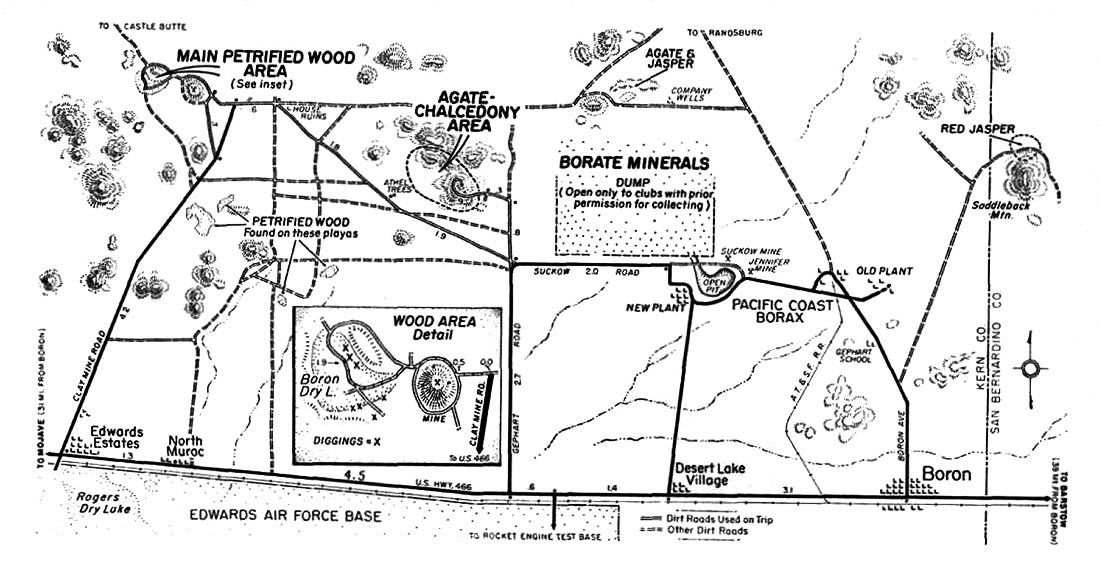

Boron area rockhounding map featured in March 1958 Desert Magazine article.

During one of my return visits with colleagues, David kindly led us on a short drive in his 1974 K5 Blazer (his rock-collecting ride) to the agate-chalcedony area just west of the Rio Tinto Mine north of California State Route 58. This site was featured in a March 1958 map published in the Desert Magazine article “Rockhound Bonanza at Boron.” The spot is also the location of his grandfather’s original locally sourced stone homestead built on a hill above the collection area.

After we parked, David handed me a bucket and a geologist’s pick, although he made clear that the collectible specimens at the site would be primarily “in float”—meaning the gems could be easily spotted and collected from the ground’s surface, having been dispersed by water flows over time. As we walked, David excitedly picked up a rock or two, handing the stones over to us to examine while explaining their provenance and name, along with anecdotal accounts of the area such as his own family’s local history.

One of his stories concerned some strange goings-on that his grandmother had witnessed first hand during the 1950s at the southern side of the hill where the present-day remains of the Garrett Corporation’s Boron facility lay in ruins along the access road we used. Garrett—a contractor involved with the Air Force’s top-secret Suntan Project—was conducting classified research for a high altitude fuel using hydrogen, during 1956-1958. Although considered largely unsuccessful, after millions were spent on its development, Suntan led directly to the first rocket engine that flew using liquid hydrogen. Supposedly this abandoned site is where the engine and cryogenic component tests were conducted. The existence of this project remained secret until 1973.

David continued picking up rock after rock, first a bit of petrified wood, next a chunk of jasper, then a fragment of an exploded geode revealing slivers of sparkling crystals, chalcedony and other prized agates of varying colors. We soon learned we were walking over a swath of semiprecious gemstone treasures that only needed to be noticed by a trained eye to be appreciated and scooped up for the taking.

Cartoon form March 1967 Desert Magazine article.

Rockhounding reached its height of popularity in the U.S. during the 1950s and 1960s, although interest in this recreational hobby originally started in the 1930s. This form of amateur geology was well suited for dry, arid regions of the American Southwest. Rockhounding enthusiasts found that the exposed barren landscape of the Mojave Desert surrendered its geological treasures readily and in abundance.

Throughout time, humans have collected and coveted gems, rocks and minerals for a variety of purposes, including tools, spearheads, weaponry, ornamentation or as a form of currency in trade and commerce. Of course, the Mojave Desert has a well-documented history of mineral prospecting and mining from the mid-nineteenth century to the present.

Desert Magazine— a regional publication centered on history, culture, geography and natural history of the American Southwest founded in 1937 by editor/writer Randall Henderson in Palm Springs, California—began to regularly promote rockhounding very early on. To introduce their readership to this activity, they brought on Harvard-educated gemologist/geologist John W. Hilton to write a regular column for the magazine.

A man of many talents, including landscape painting and musicianship, Hilton owned a gem shop and gallery near Indio, California. He ran with a rather interesting crowd that included James Cagney, General George Patton, President Dwight Eisenhower and Howard Hughes—who had once personally delivered live Maine lobster via airplane to Hilton’s shop for his daughter Katherine’s birthday party.

Hilton published a string of articles into the 1940s with titles such as “Happy Hunting Ground for Gem Collectors” or “Rock that Makes You See Double.” In his first installment in February 1938, the photograph introducing Hilton looks remarkably like a geologist ax-wielding Doc Holliday portrayed by a youngish Val Kilmer in the 1993 film Tombstone.

At one of Hilton’s commercial mine claim operations located in the Borrego Badlands near the Salton Sea, he and his partner Dr. Harry Berman discovered in 1936 a deposit of pure crystal calcite (calcium carbonate) known as Iceland spar. A natural polarizer, this form of high-clarity, transparent calcite exhibits certain optical qualities such as birefringence, which causes the crystal to refract light into two separate images. This same optical-grade material first mined by Hilton and his friend Guy Hazen was later sold to Edwin H. Land’s Polaroid Corporation for the production of precision World War II gun sights used in anti-aircraft target weaponry that some claim gave the U.S. military a leading technological edge over their enemy.

“Sunstone” (thought to be Iceland spar) is speculated to have been an important navigational aid for Vikings sailing the North Atlantic under cloudy conditions. Using the crystal’s polarizing qualities, sailors could determine the position of the sun within a few degrees. More recently, Iceland spar is being used in research to make small objects invisible.

As rockhounding gained in popularity a number of gem and mineral clubs and societies formed throughout Southern California and beyond. Men, women and children—entire families equally participated in weekend field trips to remote desert locations in search of rare mineral finds for their rock garden, display cabinet or as conversational pieces shared during happy hour. Some collectors specialized in gathering mineral specimens featuring optical properties, while others sought only those displaying phosphorescent or other similar traits. Mineralogical tours were promoted as a healthy and satisfying way to spend time outdoors.

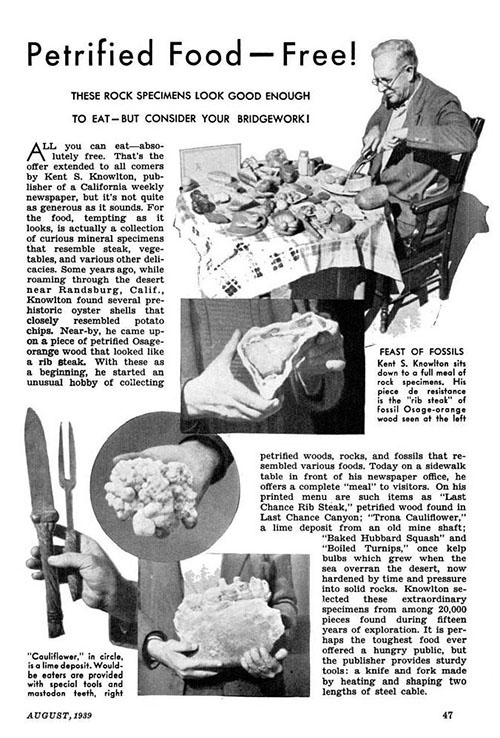

Petrified Foods—Free! Popular Science, August 1939.

One gentleman named Kent S. Knowlton, who was featured in the August 1939 issue of Popular Science, built a collection called “The Original Rock Dinner” displayed as a tabletop meal that consisted of rib steak, potatoes, cauliflower, baked squash, turnips, desert clams, head cheese, pigs’ knuckles, peanut candy, ginger cakes, salad, piccalilli sauce, potato chips, mint Jello, liverwurst and other mid-century culinary delicacies all sourced in or nearby Randsburg, California. The table salt was real and the pepper was black sand. The paper menu stated that if the diner felt dentally challenged by these “petrified foods,” they could “rent” a set of teeth in the form of a fossilized elephant’s jawbone. This unusual collection continues to be on display at the Rand Desert Museum, in Randsburg.

The tools of rockhounding have always included a prospector’s pickaxe, sample bag, magnifying glass, a handbook for identification, a “hardness set” for determining the degree of hardness from one to ten, and a “streak plate” used to identify a specimen by scratching a mark on the plate’s surface (some minerals leave no streak; others produce a color different from the actual material). True pros lick a specimen to reveal its identifying characteristics disguised by the “desert varnish” rather than wetting it with one’s finger. Once identified, it is important to note the location where the specimen was originally sourced. A plethora of advertisements for rock cutting and polishing equipment sized for hobbyists have consistently appeared throughout the back pages of (now defunct) Desert Magazine and other lapidary-themed journals, allowing for processing of collected specimens into finished pieces from home-based shops.

On a few occasions, an amateur mineralogist would actually find something not previously identified. Such was the case of Mrs. Zola Barnes of Los Angeles, who located in the Gold Gulch district of Nevada a new material exhibiting lovely alternating bands of red rhyolite and white chalcedony, which became known as Zolarite.[2]

Even early on, many articles appearing in Desert Magazine stated in alarm that prime public gem and mineral sites were being exploited and over collected. Vincent Morgan, the interview subject of the magazine’s 1958 feature on Boron rockhounding, was quoted stating, “Most collectors are reasonably conscientious, but some are greedy. We must teach conservation and moderation to all mineral collectors and the instrument for that educational process is the local club.”

Addressing the dramatic negative shift in the mineralogical landscape and the effects of “wreckreation” in her 1971 foreword for the popular Desert Gem Trails, author Mary Frances Strong commented, “Those who love and respect the desert have seen it invaded, raped and desecrated by hordes of people who swarmed over the land intent only on their own selfish pleasures. Like locusts, they have ravished the vast deserts, which, though of rugged beauty are extremely delicate, ecologically speaking. What eons of time and might forces of erosion could not accomplish, man has done in a decade.” Strong encouraged her readers to practice a “leave no trace” ethic and to collect only what one could actually use, while being mindful and sensitive of desert surroundings. I suggest that we should continue minding Strong’s sound advice now and into the future.

Today’s rockhounders need to be aware of current rules and regulations governing the collection of minerals and gems on public lands. The BLM’s Rockhounding webpage states that “reasonable quantities” of rocks, minerals, semiprecious gemstones, and invertebrate and plant fossils of nonscientific importance may be collected for personal use. The collection of petrified wood is limited to twenty-five pounds per individual per day. The collection of vertebrate fossils and all types of colored silica artifacts of historical Native American origin are illegal on public lands without the appropriate paleontological or archaeological permit. Collectors need to obtain permission to collect at registered mining claims and at other private properties. Motorized vehicles must stay on designated open roads, as cross-country travel is illegal. Driving in designated Wilderness Areas is also illegal. This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] Jeff Hecht, City of Light: The Story of Fiber Optics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 74.

[2] Howard Kegley, “They Call ’Em ‘Rockhounds,’” Desert Magazine, January 1940, 31.