The General Mining Act of 1872 encourages exploration, claiming and mining of valuable mineral deposits by U.S. citizens of “ordinary prudence” within unclaimed public lands open for mineral entry.[1] The Diggings™ website states that 3,856,269 mining claims have been recorded within the U.S. Only 10 percent of these claims are active. According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), there are 139,591 records of mines in North America. California leads the nation with its inventory of 25,673—more than double that of the runner-up, Nevada.[2] Even so, most of these mines were closed or abandoned long ago.

Numbers aside, detractors consider the statute archaic. It imposed little, if any, regulation on the mining industry, thus encouraging the rampant development and exploitation of the nation’s mineral resources. Opponents of mineral extraction industries argue that the law provides a “free ride” for mining interests. Indeed, during the 150 years the act has been in place, no royalty has been levied on metallic mineral profits. Considering that $1 billion of metal is mined annually, and $400 billion worth of gold and other lucrative minerals were extracted in public lands over time, it is shocking that not one dollar of compensation has reached the American public, which, in concept, should share these riches.[3]

Moreover, per-acre patent fees allowing for the outright purchase of mineral-bearing public lands—set at $2.50 for placer claims and $5 for lode claims when President Ulysses S. Grant first enacted the law—have remained unchanged. Although Congress imposed a moratorium on mineral patent applications on October 1, 1994, and no new patents have been issued, mining watchdog groups argue that more than three million acres of public land have been “given away” for a pittance to foreign and domestic mining entities since 1867.[4]

For instance, Canadian-owned Barrick Gold Corporation, which owns 75 percent of gold mining interests in Nevada, secured patents for over 1,800 acres of public land in 1994—just before mineral patenting had ended. Barrick paid $9,000 for these combined patents at the time assessed to produce over $10 billion worth of gold. In 2018, Barrick’s worldwide operations generated $7.24 billion and provided its shareholders with a 33 percent increase in annual dividends.[5]

Contemporary lawmakers have largely failed to modernize or amend the 1872 law regarding royalties and other vital issues. Multinational mining corporations (many Canadian and foreign-owned) operate within U.S. public lands without paying a cent on gold, silver, copper and the other valuable metallic minerals from which they most handsomely profit.[6] In contrast, the federal government collects annual royalties from 8 to 17 percent from corporations extracting coal, oil and gas within U.S. public land and waters—representing billions of dollars in revenue. The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Campaign for Responsible Mining estimates combined lost royalties, tax breaks and federal subsidies cost the federal government and taxpayers, at minimum, $160 million annually.[7]

Beginning as early as the mid-1860s, some bold U.S. lawmakers sought to reform the industry’s egregious tax breaks and generous federal subsidies, dubbed “reverse royalties”—but with little success. In the early 1990s, the late Arkansas Senator Dale Bumpers had an ongoing debate on this divisive issue with Nevada Senator Harry Reid that continued for eight years. Notably, both Senators are Democrats. Reid, born and raised in Searchlight, Nevada, a dusty gold-mining town sixty miles south of Las Vegas, partially explained his hardline and unrelenting support of the mining industry.[8] Bumpers considered the 1872 law to be “a license to steal and a colossal scam.” Bumpers fought during his Senate tenure to see the act reformed—but to no avail. He remarked that members of Congress “who perpetuated this unbelievable scam are never held accountable because the public knows little, if anything, about the abuse.”[9]

Several bills have introduced legislation to impose royalties on corporate mining profits in past years, but the National Mining Association and other like-minded lobbyists have kept them from passing. These special-interest mining groups successfully argue that they pay their share of taxes and provide rural jobs. In 1993, former Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt attempted to rein in the industry. However, his bid fell flat after Reid publicly opposed his bill and another one that would have eliminated a tax break for corporate mining companies. The tax break in question saved the mineral extraction industry $327 million a year.[10] As long as Reid remained in office, he would thwart any similar bill that came his way.

Another failed effort to regulate industrial mining activities occurred in 2007 when the House of Representatives attempted to pass The Hardrock Mining and Reclamation Act. This bill proposed a 4 percent royalty on existing mining at unpatented claims and 8 percent on any new mining operation. Previously patented claims were exempt. Additionally, it would have set aside 70 percent of collected royalties to remediate abandoned mining claims. The remaining 30 percent was slated for distribution to communities negatively affected by such activities. Even the George W. Bush administration toyed with the idea of implementing royalties on metal mining production.[11] In contrast, Senator Barack Obama balked at imposing royalties on mining interests with the 2007 bill, commenting“legislation that’s been proposed places a significant burden on the mining industry and could have a significant impact on jobs.” At the time, Obama was running for president, and Nevada, as it turned out, is a crucial swing state.[12] The U.S. Senate eventually killed the bill in 2009. Another version of this bill similarly died in 2011.

Senator Tom Udall (D-NM) and Chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ) co-sponsored a 2019 reform bill requiring a 12.5 percent royalty on any new hardrock mining operation and an 8 percent royalty on existing mines generating more than $50,000 in annual income. In addition, the bill allocates 25 percent of collected revenues for the mine’s home state and the balance to a federal reclamation fund.[13] Whether or not Udall and Grijalva successfully pass the bill remains to be seen.

Notably, eighteenth and early nineteenth-century mining operations were minuscule compared with today’s open-pit cyanide heap leach operations. Consider the massive scale of the largest gold mine in North America—the Goldstrike Mine owned by Barrick Gold Corporation—geographically positioned along the microscopically gold-rich Carlin Trend of northeastern Nevada. The company’s website states that the “ultimate pit will measure approximately two miles east to west, 1.5 mi[les] north to south, and have an average depth of approximately 1,300 ft.”[14]

Regardless of their physical footprints, many smaller historical mines have resulted in lingering environmental damage, dangerous physical safety hazards, and, at times, staggering ecological devastation. Thousands of historic, abandoned small-scale mining operations remain physically accessible, and many require extensive environmental site remediation. With owners long gone or bankrupt, the federal government and taxpayers foot the bill when ecological remediation is needed.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) manages these abandoned extractive follies on public lands throughout the West. Although the actual number of historic mining sites in the California Desert District is unknown, a 2014 USGS study estimates that there are 22,730 abandoned mine sites with 79,757 individual features located across 35 million acres of arid lands of central and Southern California. The BLM’s Abandoned Mine Lands (AML) program, whose mission is to “mitigate and remediate hard rock AML sites on or affecting public lands,” suggests that there are 17,060 AML sites in the Mojave Desert that require further study and possible remediation.15

It should come as no surprise that the 1872 act did not include a requirement for post-operational mining reclamation—the idea was unheard of at the time. It would take 100 years—with the passing of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) in 1976—for the implementation of reclamation requirements. The Carter administration first enacted the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) of 1977 to counter the environmental effects of coal strip mining. SMCRA additionally administers abandoned mines on federal lands and requires all active mining operations to post a bond to ensure adequate funds are set aside for reclamation purposes. Two years before SMCRA, the California state legislature enacted the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act (SMARA) “to address the need for a continuing supply of mineral resources, and to prevent or minimize the negative impacts of surface mining to public health, property and the environment.”

In 2003, the California State Mining and Geology Board adopted regulations requiring the backfilling of open-pit metallic mines within the state “to a condition that approximates the natural condition of the surrounding land and topography.”16 Although most large open-pit metallic mines are not required to backfill the entire excavated pit upon closure, they must recontour the pit’s slopes to lessen the steepness of the grade. Spent heap leach pads, overburden and waste piles, sometimes miles in length, must be graded and revegetated. All buildings, mills and other structures must be dismantled and torn down.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lists industrial metallic mining as the largest toxic polluter in the nation. Consequently, many former mining sites require costly and continuous environmental, health and safety remediation. Closure or reclamation bonds have been mandatory for mineral mining operations in the U.S. since 1977 to guarantee that former mining sites are remediated and reclaimed once operations cease. However, it is essential to note that many mining companies are inadequately financed to do so due to “self-bonding.” Once bankrupt, many underbonded mining operations abandon the site, leaving future cleanup costs in the hands of the taxpayer—illustrating how current financial assurance of reclamation bonds fails to cover the actual, long-term cost of reclamation.

Responding to the failed self-bonding practice, the Obama administration later mandated that the EPA force hardrock mining operations to secure separate sources for mine cleanup funding. Unraveling years of hard-won environmental regulation at many federal agencies, the Trump administration reversed this decision in late 2017. However, the reversal is currently being contested in court, as it violates the 1980 law that spawned the Superfund program. Further, the Trump administration has very enthusiastically reopened 1.3 million acres (more than 2,000 square miles) of mining claims within the California deserts during 2018 that had been previously made off-limits by the Obama administration.

All in all, open pit, industrial-scale metallic extraction processes—especially those involving the cyanide heap leach method—are highly problematic on many levels, so a detailed overview of this technique is warranted.

Cyanidation is a hydrometallurgical leaching method where aqueous cyanide is used to dissolve and extract microscopic gold and other precious metals from lower-grade ores. As early as 1783, chemists knew that aqueous cyanide solution could dissolve gold. However, it took nearly 100 years for the technique to be refined and utilized at large-scale gold extraction operations.[17] In 1887, Scottish mining chemists developed the MacArthur-Forrest cyanide process, first implemented successfully at South Africa’s Witwatersrand mining district in 1890. The Mercur Mine in Utah was the first American outfit to use the process during the following year. By suspending the crushed ore in an aqueous cyanide solution, up to 96 percent of pure gold could be recovered. Cyanidation would revolutionize and replace the mercury amalgamation process at more extensive mining operations by the 1920s. Today, the process is used in 90 percent of gold production worldwide.

Although cyanide is highly toxic and capable of causing immediate death in various forms, it is relatively cheap and readily available for industrial purposes. In addition, cyanide, for the most part, is biodegradable; exposing cyanide to sunlight, oxidizing it with bleach or hydrogen peroxide, and allowing microbial processes to convert it into ammonia are ways cyanide is neutralized or broken down.[18] Although cyanide is manufactured primarily for industrial mining purposes, it also occurs naturally. Many plants and organisms, including some insects, certain bacteria, fungi, and a surprising number of common vegetables, including cassava root, seeds, and pits from various stone fruits, contain the chemical.

The mining industry was transformed again through an updated variation of the cyanidation process in the 1970s with the widespread implementation of industrial-scale, open-pit cyanide “heap leaching”—which allows profitable mining of lower-grade gold ores, containing as little as .02 ounces. Because many conventionally mined, high-grade ore bodies were already exhausted, mining industry enthusiasts welcomed the technology when the U.S. Bureau of Mines began promoting the cost-effective technique in 1969.[19] However, detractors of the cyanide heap leach method have compared it to “dirt mining.”

Indeed, cyanide heap leach operations require massive earthmoving, along with the energy to do so, plus billions of gallons of groundwater for processing ore. At some Nevada heap leach operations, whose production equals three-quarters of all gold mined within the U.S., up to 100 tons or more of material is unearthed to yield a single ounce of gold.[20] Earthworks, a mining watchdog group, estimates that the production of one gold wedding ring today generates at least twenty tons of mine waste along with thirteen pounds of toxic emissions containing lead, arsenic, cyanide, and mercury.[21] The EPA ranks industrial-scale metallic mining as the nation’s top polluter of chemical compounds released into the environment.[22]

The heap leach process is a closed-loop system where highly alkaline aqueous sodium cyanide solution is dripped or sprayed onto industrial plastic-lined concrete pads laden with massive mountains of ore.[23] Once applied, the oxygenated “lixiviant” or leaching solution percolates through the heap, binding with the gold, eventually collecting into underground piping leading to the “preg pond,” which, as its name implies, is “pregnant” with microscopic gold. The process takes several weeks to months to complete depending on the ore grain size and the pad’s height.

This concentrated gold-bearing cyanide liquor is pumped into the recovery plant’s giant vertical tanks containing very fine activated carbon. My friend Tom O’Donnell, a former metallurgist at the Rand Mining Company (RMC) and longtime Randsburg, California, resident, gleefully states how “the gold loves the carbon.”[24] Indeed, attracted to the carbon, the gold abandons the cyanide to wait for further processing. Then, the now-barren cyanide solution is replenished and recirculated onto the leach pad. If the massive mountain of ore collapses during the process, the entire operation is halted so workers can bulldoze the heap back onto the pad. The ongoing threat of cyanide escaping this closed-loop system is not taken lightly; “You never, ever, let that stuff get off that pad. You got people there 24 hours a day, and that is their job to keep that cyanide inside the fence,” O’Donnell states.

After filtering this gold-bearing carbon concoction, caustic soda is added, dissolved, and heated, which releases the gold from the carbon to produce a highly-concentrated gold-bearing solution. Next, this mixture is pumped into a “cell” with positive and negative termination, where it undergoes the electrowinning process first developed in 1807. Electrowinning uses a strong electrical current that forces the gold to collect in the cell’s negatively charged steel wool that is recovered by melting it with flux in a furnace heated to around 2,100˚ Fahrenheit. Eventually, the iron rises to the surface, and the heavier gold sinks to the bottom. Finally, the iron and flux are discarded, leaving the remaining gold to be poured and molded for further refinement.

Magical, yes, but when all is said and done, a number of the world’s largest cyanide heap leach operations have failed miserably over time. The greatest cyanide-related catastrophe in the U.S. occurred at the Summitville Mine in southwestern Colorado. In 1992, after leaching around ten million tons of gold and silver ore over five years, resulting in 160 million gallons of cyanide-laced wastewater, Canadian-based Galactic Resources Ltd. filed for bankruptcy and abandoned the site. Soon after, nearly 85,000 gallons of cyanide-contaminated waste along with acid mine drain containing heavy metals had leaked into the neighboring watershed, including the nearby Alamosa River. The calamity killed all fish and other riparian wildlife over a seventeen-mile stretch of the river.[25] The mine became a Superfund site in 1994, eventually requiring $250 million of federal funding for remediation plus $2 million per year that Colorado taxpayers will pay over many years to come. Summitville Mine’s owner, Robert Friedland, who holds dual citizenship in Canada and the U.S, ended up paying only $20 million out of pocket for remediation work on the Alamosa River. Summitville took in an estimated gross income of $150 million while it was operational.[26]

The Zortman-Landusky mines, bordering the Fort Belknap homeland of the Assiniboine (Nakoda) and Gros Ventre (Aaniiih) Nations in the Little Rocky Mountains of north-central Montana, provide another example. The Zortman-Landusky, one of the first heap leach operations in the country, had numerous cyanide spills while operational, with the most significant single incident involving 50,000 gallons.[27] Over time, related surface and groundwater pollution has resulted from the mine’s gold and silver mining activities in the form of extensive acid mine drainage with arsenic, lead and other heavy metal contamination. The mine’s owner, Canada-based Pegasus Gold Corp., began mining operations in 1979. Nineteen years later, the mine went bankrupt and walked away from this ongoing disaster that has to date cost $100 million with an additional $2 million a year paid by the state of Montana to contain the contaminated wastewater. Even though Pegasus set aside bond monies for such disasters as required by law, taxpayers have taken up the bulk of the reclamation costs, with the total clean-up estimated to be in the tens of millions of dollars.

Understandably, a Montana citizens’ initiative banned cyanide heap leach operations in 1998. Wisconsin followed in 2001. Over time, other disastrous spills have occurred in North America. These include the 2014 Mount Polley Mine tailings pond dam breach at Imperial Metals in British Columbia and Colorado’s 2015 Gold King Mine acid mine drain spill. At Gold King, the EPA and subcontracted workers charged with cleaning up the abandoned mine ended up accidentally releasing toxic water into the Animas River watershed. Cyanide heap leach mines continue to operate in California and Nevada—even though the EPA states that mining interests have polluted streams in 40 percent of the West’s watersheds.[28] In 2017 alone, metallic-bearing mines generated nearly two billion pounds of toxic waste—equaling half the amount produced by all industries nationwide.[29]

Nevada, the nation’s largest producer of gold, currently allows new mines to begin operations with full disclosure that they will pollute the surrounding watershed—possibly in perpetuity—which could require continuous remediation to clean up contaminated groundwater, streams and pit lakes. The 2019 Udall/Grijalva bill, if passed, would ban this practice.[30]

Jim Kuipers, a hardrock mining engineer consultant, stated in a 2003 Mineral Policy Center report that taxpayers will foot $1 billion to $12 billion in projected clean-up costs at abandoned hardrock metallic-mining sites across the country due to lax regulation and inadequate bonding. The EPA says this figure is higher. It estimates $35 billion or more to remediate abandoned mines found across thirty-two states.[31]

But this story is more complicated than it appears at first glance. Tom O’Donnell, a.k.a. “Ordinary Tom,” defends the process, having overseen the cyanide heap operation at RMC from 1989 to 1994.[32] RMC’s 2,520 acres of public and private holdings included the historic Baltic, Lamont and Yellow Aster mine, whose original “glory hole” was subsumed by RMC’s heap leach operation. During active production, RMC, on average, processed 45,000 tons of material, ultimately recovering one million ounces of gold over the eleven years the complex was operational.[33]

Tom, a kind, gracious, progressively minded man, now in his mid-sixties, began his career path in the Air Force where he served in Vietnam as a Crash Rescue Firefighter. Having been honorably discharged from the military in 1968, Tom worked various jobs throughout the western U.S. and Alaska. These included a stint as a photojournalist stringer for the Seattle-Post Intelligencer, a cook on a tugboat, a logger and a long hauler. After delivering a load to a mine in New Mexico, he was hired on the spot as a hardrock miner, which led him back to Alaska. He eventually returned to New Mexico, enrolling at Socorro’s New Mexico Tech chemistry program. After graduation, he worked at several mining operations, including RMC, plus a later stint at Panamint Valley’s Briggs Gold Mine near Ballarat, California. But by his late thirties, he knew that he could physically toil underground for only so long. Overseeing heavy equipment operators, massive earthmovers and construction crews required for this new type of “mining” operation at RMC served him well.

O’Donnell is fascinated by the alchemy of the cyanidation process, stating that “we don’t know exactly how the gold complexes with cyanide, or, for that matter, why it releases into the carbon.” When asked about the downside of the cyanide heap leach process, including its poor environmental report card, he’ll defend his work at RMC, stressing, “who lives closest to the mines—the miners!” Although our opinions differ about the merits of cyanide heap leach technology and mining microscopic gold and other profitable metals at such a massive scale, I respect Tom immensely; he is open to debate and willing to consider multiple sides of this contentious issue. Tom and others like him are proud of their mining industry careers, which provide much-needed skilled and higher-than-average paying jobs in rural regions of the West. His friendship offers an insider’s look into an industry that I would not have encountered in my day-to-day life if I had not embarked on a project looking closely at the culture and geology of the Mojave Desert.

Large-scale industrial mining in Randsburg faded out during the early 2000s when RMC shuttered operations, leaving off-roading and related tourism as the primary economic force driving the community. The BLM manages the Rand Mining District’s public lands, including the plethora of abandoned mines within and surrounding the town.

While operational, RMC, like many other industrial mines of similar scale, had its share of accidents and wildlife fatalities, but no single incident was exceptionally newsworthy.[34] Stream and watershed contamination are less of an issue in the Mojave Desert due to the region’s lack of prominent surface aquatic features near heap leach mining operations.[35] Still, other severe environmental challenges, including ground, airborne and groundwater contamination, can occur at these sites.

In early 2006, the Department of the Interior (DOI) determined that the Rand Mining District (RMD) had elevated levels of arsenic contamination measuring 4,700 times higher than what the EPA considers acceptably safe, triggering a rarely-enforced DOI Flash Report.[36] Arsenic is a common, naturally occurring element. Generally, it is a significant component of gold deposits found within the western U.S. Consequently, arsenic levels are often elevated in areas extensively mined, leading to environmental contamination.

Arsenic can be toxic and can kill both humans and wildlife. In addition, mining processes unearth and concentrate arsenic in spent mine tailings and waste ponds, which sometimes leads to groundwater contamination. The 2007 DOI report identified “arsenic contamination in over 3,000 acres of mine tailings and 500,000 tons of additional mining-related waste rock” within the RMD, estimating the cost to clean up at $170 million—at the time considered to be the largest BLM remediation project in its history.[37] Responding to the DOI report, the BLM initiated its Abandoned Mine Lands (AML) program in 2009 to deal with the issue.

In addition to arsenic contamination, high levels of toxic mercury, lead and other heavy metals were measured in the RMD. However, airborne arsenic carried by desert winds, exacerbated by off-road recreation, is still the primary health concern. The 2007 DOI report listed as many as 30,000 visitors utilizing the area on holiday weekends. For many years, off-roaders drove on the popular Route 110 trail leading across a sixty-acre arsenic-contaminated former mill site before it was closed in 2007 because it potentially exposed riders to toxic dust. In addition, off-highway vehicle (OHV) trails on public lands within the surrounding RMD were posted with warning signs and cordoned off, thus limiting recreational access.

Because Randsburg is economically dependent on OHV recreation and related tourism, closures proved controversial for business owners and many residents. However, after BLM oversaw mitigation work at the mill site that included fencing off and capping the arsenic hazard with an earthen berm, rerouting Route 110 alongside the fence line, and posting arsenic warning signs, the trail was reopened to riders. When asked about the arsenic contamination, O’Donnell casually brushes the issue aside, commenting, “Well, no one in town has died from arsenic as far as I know, and we have had our share of old-timers that have lived to nearly 100.”

In 1984 and 1997, the BLM allowed Randsburg and other area residents to purchase titles to their properties but only if buyers agreed to indemnify or hold harmless the federal government regarding exposure to hazardous materials resulting from the area’s historic mining activities. BLM supervisors had known about the district’s arsenic contamination but failed to officially test and assess how severe and widespread the hazard was. A 2008 DOI audit report criticized the agency for its marginalization of the arsenic issue and its neglect to identify and secure physical hazards at the many abandoned mines found across the public lands they manage. Indeed, the report stated that some BLM employees had even received threats after identifying grossly contaminated or unsafe former mining sites. Their supervisors worried that the agency would be more susceptible to lawsuits by identifying the hazards and told the informers not to pursue the issue.[38]

Physical safety hazards at abandoned mines are not exaggerated. Every year, both seasoned and amateur explorers, along with a number of unwary victims, are seriously injured or die after they knowingly or unknowingly enter one of these many dark, subterranean spaces. Accidental deaths have resulted from falling or driving vehicles into shafts, encountering poisonous gases or no air deep inside tunnels, or drowning in a flooded chasm. Some are crushed when aging mine supports fail. Others have met their demise after being blown to bits by long-forgotten stashes of dynamite.

Forty-plus accidental deaths have been documented in abandoned California desert mines since the mid-1970s. For example, in separate incidents, three people accidentally fell to their death upon entering the “ant trap” funnel mineshaft of the Goat Basin Mine bordering the eastern edge of Joshua Tree National Park. In addition, several deaths have occurred in the RMD, including that of 21-year-old Matthew Frey, who would plunge to his death in November 2004 after riding his motorcycle up a moderate incline and falling into a 700-foot-abyss in the neighboring Spangler Hills OHV area.

Two years before Frey’s death, a 14-year-old boy was luckier—this dirt bike rider tumbled into a nearby 780-foot shaft but survived after landing on a support beam some 200-feet below. Sterling White, who administers the BLM’s California AML program, commented that Randsburg’s Baltic Mine alone has 300 holes that require mitigation. In 2019, the BLM planned to secure sixty mining-related features in the Red Mountain area. Indeed, out of the thousands of identified abandoned mining sites, each mine may have up to a dozen hazardous mining-related features that require securement. Millions of dollars have been spent so far in an ongoing effort to safeguard these mines.

Other OHV-related fatalities resulting from falling into abandoned mineshafts occurred in the Calico Hills OHV area and other parts of the Mojave Desert. In 2007, a young girl died when she and her sister accidentally drove their all-terrain vehicle into a 125-foot mineshaft while riding in the Windy Point Recreation area outside Kingman, Arizona. Unsuspecting tourists have nearly backed into holes large enough to swallow entire vehicles. A rancher on horseback survived a fall into a collapsed horizontal shaft or adit. Unfortunately, most livestock and wildlife under similar circumstances do not make it out alive. Occasionally, human remains are dumped in mineshafts. The BLM, NPS, private landowners and recreational off-roading clubs such as the Havasu 4 Wheelers have secured some of the most egregious hazards, often using steel bat gates. Still, many abandoned mines remain humanly accessible after fences, gates or warning signs are illegally removed. However, the BLM discourages community involvement—since individuals or groups independently securing mineshafts become legally liable for any accident or death that may occur after the modification.

Abandoned underground mines have found reuse as Cold War-era bomb shelters, and more creatively as a community-led time capsule project. For example, various municipal civil defense entities have in the past outfitted subterranean spaces for nuclear fallout shelters—some equipped with enough supplies to support 17,000 individuals with decontamination facilities and a potable water supply. Such was the case of U.S. Borax’s tunnel shelter constructed within the old Suckow colemanite mine, now part of the open pit Rio Tinto Mine in Boron, California. Victorville provided a similar service for 200 individuals at the nearby Apex Mine. The Sidewinder Mine, located between Victorville and Barstow, could host 859 people in the event of a nuclear war, providing them with a 200-bed hospital, a library and an exercise room in exchange for materials, cash or labor to secure their spot. This shelter also housed a seed bank.[39]

Rosamond, California’s 300-foot-long Tropico Time Tunnel, housed in a former gold mine of the same name donated for the purpose, was sealed with concrete on November 20, 1966.[40] Contained within were a brand new Yamaha motorcycle, a baseball autographed by Willie Mays, a model of the XB-70 bomber, a typewriter, twelve copies of the Antelope Valley Press, a packed suitcase, a female mannequin and a local’s favorite fishing shirt among many other domestic and everyday objects donated for the purpose by local residents. The time capsule was the brainchild of Jack Tomlinson, a San Francisco State University biology professor. The public mine sealing event coincided with Kern County’s centennial. The “unsealing” of the capsule is scheduled for the county’s 1000th birthday in 2866.[41]

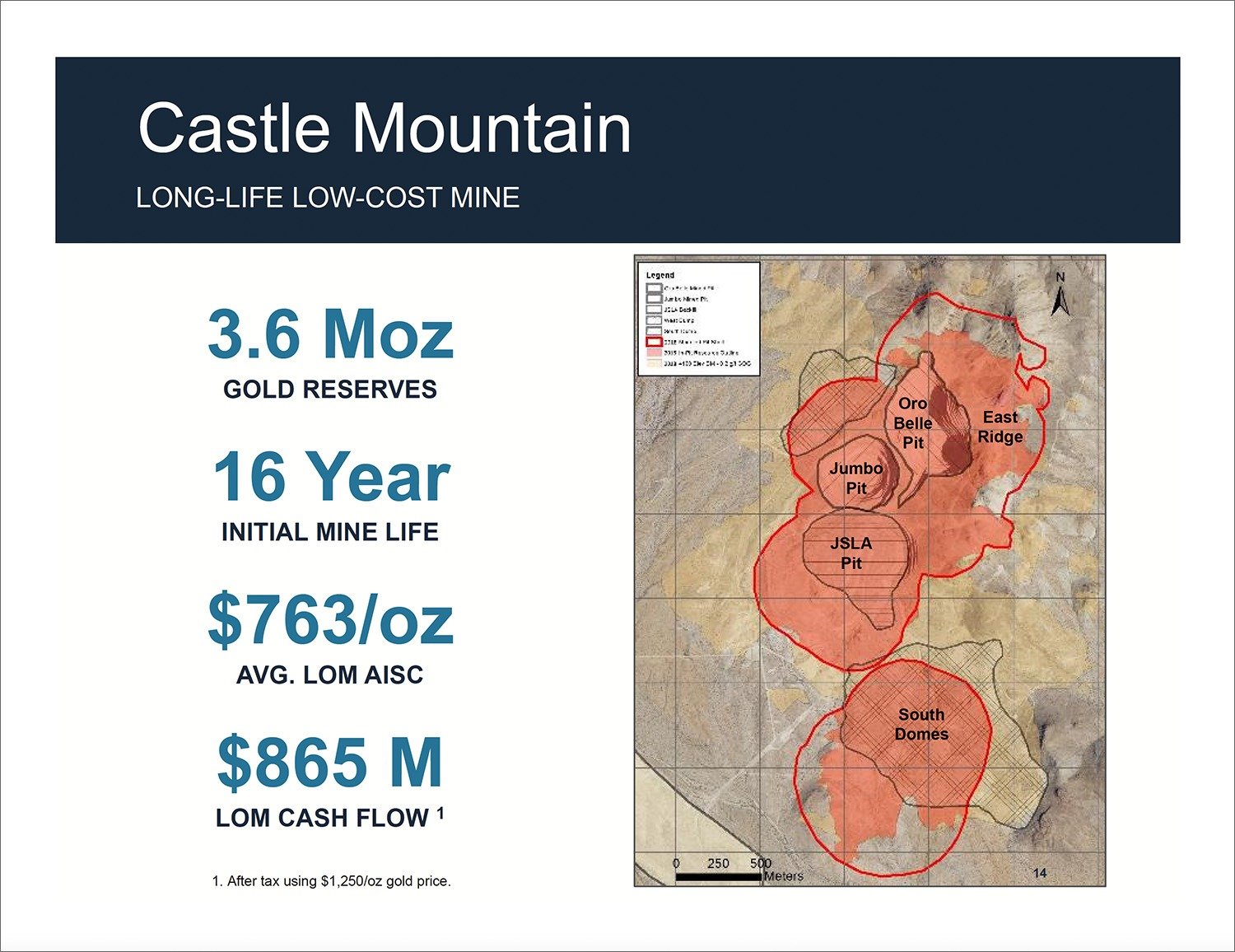

This July 2019 Equinox Gold corporate presentation states potential future financial figures for their Castle Mountain mine project that is now surrounded by the Castle Mountain National Monument, designated by President Obama in January 2016. Source: Equinox Gold

A few miles north of the Tropico Mine is the only industrial cyanide heap leach operation active in the Mojave Desert. The Canadian-owned Golden Queen Mine LLC in Mojave, California, operates around the clock on Soledad Mountain, located just west of State Route 14. Gold was initially discovered here in 1894. Along with Randsburg’s Yellow Aster, these mines historically produced half of all gold mined in Kern County. Consolidation of Soledad Mountain’s mines into the Golden Queen Mining Company occurred in 1935. Golden Queen operated until 1942, when the Federal Government enacted Limitation Order L-208. The order effectively outlawed the mining of non-strategic metals such as gold and silver during wartime. As a result, most of the Mojave District’s gold and silver mines have remained inactive since World War II.

The company currently operating Golden Queen purchased the mine in the mid-1980s but did not commence operations until 2016. As of July 2019, Golden Queen LLC’s stock was listed at $0.0155 per share. In addition, its website published a one-month loan payment extension for $75,000 posted on January 31, 2019.

Further east, on the southwestern slope of the Panamint Range near Ballarat in Inyo County, is the inactive Briggs Gold Mine. The mine is named after Harry Briggs, who operated a mill and cyanide plant at nearby Manly Falls during the 1930s. The CR Briggs Corporation began its open-pit heap leach operation in 1996, producing 550,000 ounces of gold until it shuttered operations in 2004.[42] CR Briggs was controversial due to its proximity to Death Valley National Park. When gold prices rose in 2009, Atna Resources LTD reopened the mine but went bankrupt in 2015. DV Natural Resources, LLC, a Virginia-based company, now owns the mine. However, renewed attacks on the 2016 Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) by the Trump administration previously protecting Panamint Valley from further industrial mining may allow Briggs to resume operations, along with a proposed lithium mine on the valley floor.

Southeast of Briggs and about 100 miles west of Las Vegas, the Castle Mountains rise out of northern Lanfair Valley. The Hart Mining District had previously sprung to life here in 1907 when gold was discovered. Hart faded out by 1915, but seventy-five years later, Viceroy Gold Corporation would resume mining operations via cyanide heap leach until they, too, closed in 2001. NewCastle Gold Ltd. would purchase the 1,375-acre site in 2012 and resell it in October 2017 to Vancouver-based Trek Mining Inc., Soon after, Trek renamed it Equinox Gold.[43]

A year before the sale, President Obama had signed an act designating a remote 20,920-acre parcel surrounding the mine as the Castle Mountains National Monument—just before he left office in February 2016, during his last year in office. His effort would fill a missing piece of the Mojave National Preserve that borders the mine on three sides. Obama’s designation was celebrated as a suitable compromise for both the mining industry and environmentalists, but with one hitch—the deal included an option to continue mining through 2026.

NewCastle was not entirely happy with the Obama administration’s earlier deal. By mid-2017, if only by coincidence, Representative Paul Cook (R-Yucca Valley) demanded that former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke reduce the monument by 50 percent. At the time, NewCastle was selling the mine to Trek/Equinox. The language within Obama’s monument designation likely drove the urgency to reopen the mine. It states that if no mining resumes within ten years of the act’s signing, the company will transfer its holdings to the National Park Service. In addition, Cook’s boundary adjustment request continues to be under consideration by Zinke’s replacement David Bernhardt. If realized, the mine’s activities will create ongoing vehicular traffic, noise disturbances, possible pollution and excessive groundwater depletion that will most likely impact the sensitive Piute Spring, the only perennial stream in the area.

Equinox Gold completed its pre-feasibility study in July 2018. Construction of the heap leach pad and commissioning of the processing plant is expected for late-2019. Its website states, “The Castle Mountain heap leach gold mine in California produced more than one million ounces of gold from 1992 to 2004. Equinox Gold intends to put the mine back into production with the expectation of producing 2.8 million ounces of gold and generating US$865 million in after-tax cash flow over a sixteen-year mine site.”[44] To do so, Equinox will need to re-excavate fifty-one million tons of material previously dug and used to fill the pit during earlier remediation efforts. Unfortunately, it appears that less restrictive federal mining regulations sanctioned by the Trump administration are the incentive to restart gold mining here and in other areas of the Mojave.

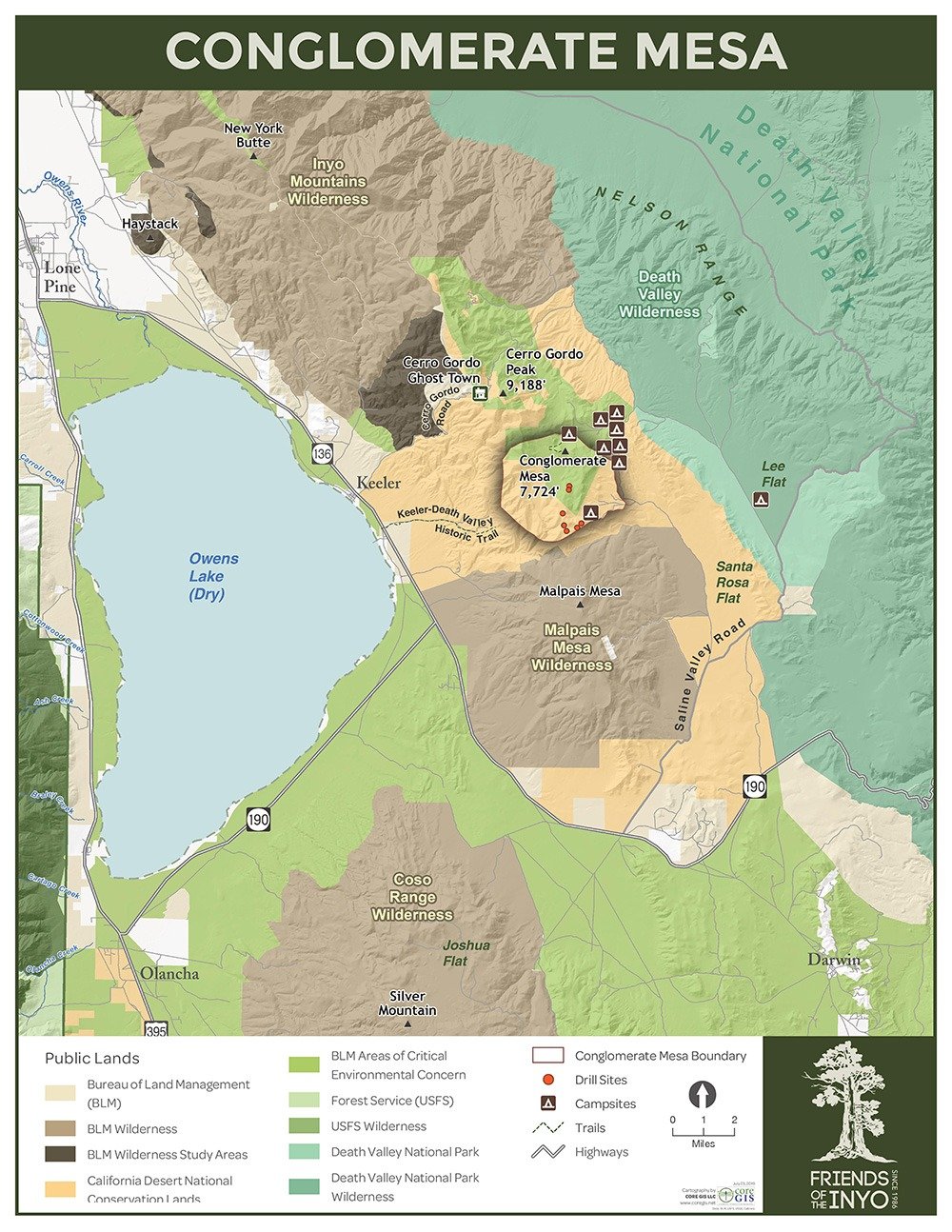

This map shows a mining company’s proposed drill sites within CA Desert National Conservation Lands. Map: Friends of the Inyo.

Perhaps the most disturbing proposal to operate an open-pit cyanide heap leach operation is at the Inyo Mountains’ remote Conglomerate Mesa, located west of Death Valley National Park. The mesa lies directly south of Cerro Gordo Peak and just north of the Malpais Mesa Wilderness. Unlike the heap leach mining operations at Soledad and Castle mountains, or even Randsburg, where extensive mineral extraction has previously occurred, mining did not occur at Conglomerate Mesa. However, charcoal was primitively produced for use at the nearby Cerro Gordo mines. In addition, Conglomerate Mesa is an essential Indigenous site for local tribes, serving as a seasonal piñon seed harvesting area. Since 1984, no less than ten mining companies have tested for gold at this rugged, roadless 7,000-acre site. All left, dissatisfied with their findings.

The most recent outfit is Vancouver-based Silver Standard Resources (now SSR Mining Inc.), owner of Nevada’s Marigold Mine, an enormous Carlin-type heap leach operation located in northwestern Nevada.[45] SSR obtained permits in May 2018 from the BLM for seven 1,000-foot exploratory test-drilling sites to be accessed entirely by helicopter for its speculative “Perdito Exploratory Project.” SSR’s proposed exploration activities require up to 1,000 gallons of water per day, supplied by a hose line laid from an existing road to the drilling site. Continuous lighting of the work area is needed for construction and test drilling. Multiple daily helicopter flights to transport crew members, drilling rig, generator, outhouses and other necessary equipment will occur in a setting devoid of human activity other than an occasional jet flying miles overhead.[46]

Conglomerate Mesa is designated California Desert National Conservation Lands under the 2016 Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) with an Area of Critical Environmental Concern (ACEC) requiring “special management attention” by the BLM. Previous test drilling at the Perdito site yielded unsatisfactory results. Not surprisingly, under mounting opposition from public and environmental groups, SSR withdrew its application by mid-summer 2016. However, the actual claim holders, partners Steven J. Van Ert and Noel Cousins, both of Chatsworth, California, have 444 twenty-acre active mineral lode claims between them, on or near the mesa covering 8,800 acres. Van Ert and Cousins were given the option to transfer the drilling authorization to themselves, providing them with an opportunity to “indefinitely pitch the project to other mining companies, leaving the future of Conglomerate Mesa in limbo.”[47, 48]

Keeping in mind that the annual maintenance fee for each Conglomerate Mesa area claim is $155, the duo must pay a total of $68,820 in federal fees a year to retain their active status.[49] According to a December 2017 article by Tom Budlong in Desert Report, if they had been successful in securing SSR to test drill here, Van Ert and Cousins would have collected $710,000 for a three-year lease option and several million more once production began, according to SEC documents filed on March 22, 2016.[50]

Friends of the Inyo and several other environmental groups filed for a formal review of the project by the BLM’s state director in November 2018, expecting to hear a decision within three months. However, the winter 2019 government shutdown delayed the decision until May 2020, when the BLM announced that the “Perdito Project will stand and exploratory drilling can move forward.”[51]

This discouraging decision allows Van Ert and Cousins to enlist a new company to explore and possibly mine at Conglomerate Mesa, shattering established wildlands protections of the mesa. The decision additionally sets a precedent allowing multinational extraction corporations to swoop into California and other western states to develop industrial-scale heap leach operations wherever they see fit.

Biologists stress that Conglomerate Mesa must remain remote and undeveloped to protect critical habitat for the endemic Inyo Rocky Daisy (Perityle inyoensis), a BLM-classified sensitive species. Furthermore, as the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia) begins its retreat to higher elevations due to climate change, the Inyo Mountains’ Conglomerate Mesa will afford a haven for this threatened species to ensure its ongoing survival.

In Nevada, the Bullfrog/Beatty Mining districts remain the only active large-scale gold mining areas within Nevada’s Mojave Desert region. Nevada is the nation’s top gold producer, with most industrial-scale gold mines located in the central Great Basin, where massive Carlin-type gold reserves are geologically situated.

At the start of 2019, the Pahrump Valley News reported that Beatty was undergoing a gold-mining renaissance. Two major international gold-mining corporations were conducting exploratory drilling, including South Africa-based AngloGold Ashanti, the third-largest gold producer in the world. In addition, several smaller players, including a couple of U.S.-based companies, were also conducting feasibility testing and research.

The Sterling Gold Mine, located fourteen miles southeast of Beatty, Nevada, was operated between 2007 and 2011 by Vancouver B.C.-based Imperial Metals—the same outfit responsible for the August 2014 Mount Polly mine tailings breach. Canadian-based Northern Empire Resources Corp. purchased Sterling from Imperial Metals for $10 million in May 2017. The property was flipped a year and a half later when Coeur Mining Inc. acquired Sterling in August 2018 for $90 million. These transactions reflect the dizzying world of speculative international metallic mine trading.

Interestingly, the Pahrump Valley News reported in March 2014 that Northern Empire’s mining activities had forced the Nevada Department of Wildlife to relocate “herds” of bighorn sheep from the active mining area, operational for a mere four years. Sterling’s general manager Chuck Stevens was quoted in the article stating, “Because the herd is so large they’re flying them out of here and shipping them out of state. They net them on the mountain range, fly them down, then we give them a physical exam, measure them, weigh them, put them in a trailer and haul them to wherever they’re going to relocate them.”[52]

In Arizona’s northwestern Mojave Desert, the historic 1902 Gold Road Mine in Oatman, Arizona, was operated as a cyanide heap leach from 1995 until 1998. It reopened from 2010 to 2016. Columbia-based Para Resources Inc., which “specializes in low-risk, low-cost gold projects in North and South America with strong development potential,” purchased this fully permitted mine for $7 million in August 2017 and began underground mining operations in late 2018.[53]

Mining will continue to be a crucial part of our nation’s economy. Many materials, chemicals and products used daily are derived from rich mineral resources extracted within the Mojave Desert. Unfortunately, gold, mainly mined worldwide for economic gain and adornment, serves no real benefit for humankind other than the continued exploitation of publicly held mineral resources. Industrial-scale gold extraction generates enormous profits for a handful of foreign-based multinational enterprises and investors.[54] Gold extraction should be the first metallic mineral levied with a substantial but sensible royalty when commercially mined. Regulators must require independent and comprehensive closure bonds that cover the actual costs of long-term environmental remediation after production ceases. And last, tighter environmental regulations are needed to rein in this unbridled industry that has for over 150 years been a congressionally favored recipient of the last remaining federal land giveaway.

Tom O’Donnell and other pro-mining advocates like him argue that industrial gold mining requires owners to assume huge upfront financial risks. He stresses that for every dollar a mining company spends internally, the investment is multiplied and dispersed sevenfold within the local economy. Those statements may be accurate, but what if the world’s massive gold extraction infrastructure is channeled instead to sustainably mine materials required for our transition towards a non-fossil fuel-based clean energy future? I suspect that more than enough jobs for miners and related industries will be available, creating sustained regional economic development in the Mojave Desert and Great Basin for years to come.

The author thanks Tom O’Donnell, Sterling White, Tom Budlong, Friends of the Inyo and Allen Metscher, co-founder of the Central Nevada Museum, for assisting her with this dispatch. This article is co-published with KCET Artbound. Visit Artbound’s Mojave Project page here. Image of an abandoned mine in Goldfield, Nevada, photographed by Kim Stringfellow.

Did you enjoy reading this dispatch? Consider supporting us with your tax-deductible donation.

Click here to learn more.

FOOTNOTES (click to open/close)

[1] Legally, “prudence” is defined as a reasonable person willing to expend additional money, time and energy into developing a mineral claim because they deem it to be of value.

[2] The Diggings™ figures are listed as of August 8, 2019. Nevada has the most active mining claims at 204,975. Source: https://thediggings.com/usa/nevada.

[3] Josh Harkinson, “Harry Reid, Gold Member,” Mother Jones, March/April 2009.

[4] “1872 Mining Law Patenting Fact Sheet,” Taxpayers for Common Sense, June 12, 2006.

[5] “Barrick Reports 2018 Full Year and Fourth Quarter Results,” Barrick press release, February 13, 2019.

[6] Associated Press, “GAO report shows royalties from hard-rock mining could generate billions for the U.S., if collected,” Missoulian, December 13, 2012.

[7] Pews’ annual figure includes the combined cost of lost royalties, tax breaks and federal subsidies. An additional $20 billion to $54 billion for yearly cleanup costs is not included. “Reforming the U.S. Hardrock Mining Law of 1872: The Price of Inaction (Fact Sheet),” The Pew Campaign for Responsible Mining: Reclaim Our Future, January 27, 2009, 2.

[8] Harkinson “Harry Reid.” Reid’s two sons work for law firms representing mining interests and his son-in-law is a pro-mining lobbyist.

[9] Senator Dale Bumpers, “Capitol Hill’s Longest Running Outrage,” Washington Monthly, January/February 1998.

[10] Harkinson, “Harry Reid Gold Member.”

[11] “Reforming the U.S. Hardrock Mining,” 2.

[12] Jennifer Solis, “Reform of 1872 law would make Barrick, Newmont pay federal mineral royalties,” Nevada Current, May 10, 2019. The Obama administration later joined lawmakers to support and implement metallic mining reforms.

[13] Solis, Nevada Current.

[14] The Goldstrike mine and nearby Cortez complex are owned by Barrick Gold Corporation, the largest gold company in the world. Source: https://www.barrick.com/English/operations/nevada-gold-mines/default.aspx.

[15] Karen K. Swope and Carrie J. Gregory, “Mining in the Southern California Deserts: A Historic Context Statement and Research Design,” Technical Report 17-42, Statistical Research, Inc., Redlands, California, October 2017. Submitted to Sterling White, Desert District Abandoned Mine Lands and Hazardous Materials Program Lead, U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, California Desert District Office, Moreno Valley, CA., 22.

[16] “California Code of Regulations (CCR) §3704.1. Metallic Mine Backfill Regulations Explained,” State Mining and Geology Board, Department of Conservation, State of California, Natural Resources Agency, 2003.

[17] Carl Wilhelm Scheele discovered that gold dissolved in aqueous cyanide solutions in 1783.

[18] Jane Perlez, “Behind Gold’s Glitter: Torn Lands and Pointed Questions,” New York Times, June 14, 2000.

[19] The agency was abolished in 1996.

[20] Perlez, “Behind Gold’s Glitter.” “Cyanide can convert to other toxic forms and persist, particularly in cold climates.”

[21] Neha Inamdar, “With This Ring: The Environmental Cost of Gold Mining,” Mother Jones, September 10, 2007.

[22] “TRI On-site and Off-site Reported Disposed of or Otherwise Released (in pounds), for All chemicals, By Industry, U.S., 2017,” Environmental Protection Agency (website), accessed July 29, 2019.

[23] Ore is sometimes processed at a crushing/screening plant but often moved onto the pad after the rock has been blown up. This type of operation is called a “run of mine.”

[24] RMC was owned and operated by Glamis Gold, Ltd., based in Reno, Nevada. RMC was later acquired by Vancouver, B.C.-based Goldcorp Inc., in 2006.

[25] Michelle Swenson, “Legacy of Hard Rock Mining in the West—Death of a River, a Community’s Response,” Huffpost, September 2, 2015 (updated September 2, 2016). Due to natural geological processes, some area streams are naturally acidic, thus exacerbating human-made pollution.

[26] “A total of 294,365 troy ounces (9,155.8 kg) of gold and 319,814 troy ounces (9,947.3 kg) of silver were recovered [from the Summitville mine].” If one does the math, considering gold prices averaged $400 per ounce during the late 1980s, Friedman’s gross income hovers somewhere around $150 million. “Summitville mine,” Wikipedia, accessed July 29, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Summitville_mine.

[27] Sara Orvis, “Zortman-Landusky Gold Mine, Montana, USA,” Environmental Justice Atlas, September 12, 2014.

[28] EPA, Liquid Assets 2000: America’s Water Resources at a Turning Point, 2000, 12.

[29] Mark Olalde, “Mining Companies Polluted Western Waters. Now Taxpayers Have to Pay for the Clean Up,” Mother Jones, March 18, 2019.

[30] Solis, “Reform of 1872 law.”

[31] EPA, Liquid Assets, 12.

[32] Nicknaming has long been part of the fraternal culture of mining.

[33] RMC operations began in 1987 and ended in 1998.

[34] David Darlington outlines RMC’s somewhat contentious tenure in Randsburg in his 1996 book, The Mojave. Darlington states that RMC ran its operation so tight in May 1994, that 150 of its hourly paid employees organized themselves under Local #30 of the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union in protest of “low wages, arbitrary dismissals and safety shortcuts.” For further reading, see David Darlington, The Mojave (New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1996), 213-221.

[345] There are exceptions in the Mojave Desert, including the seasonally flowing Mojave River, Amargosa River, plus many springs and seeps found throughout the region.

[36] “Flash Report: Environmental, Health and Safety Issues at Bureau of Land Management Ridgecrest Field Office, Rand Mining District (C-IN-BLM-0012-2007),” U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Inspector General, September 2007, 1.

[37] “Flash Report,” 2.

[38] “Audit Report: Abandoned Mine Lands in the Department of the Interior (C-IN-MOA-0004-2007),” U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Inspector General, July 2008, 1. It seems that BLM officials were worried about liability—identifying the hazards made them more susceptible to lawsuits.

[39] Swope and Gregory, Mining in the Southern California Deserts, 62.

[40] The Tropico Mine, originally called the Lida, began life as a clay mine until gold was discovered. The gold mine was worked from the 1890s into the start of World War II.

[41] Swope and Gregory, Mining in the Southern California Deserts, 62.

[42] CR Briggs’ parent company, Canyon Resources Corporation of Golden, Colorado, unsuccessfully led the fight in 2004 to undo Montana’s 1998 cyanide heap leach ban.

[43] Equinox Gold operates Imperial County’s massive Mesquite Mine, the largest-producing open pit heap leach operation in California.

[44] “Castle Mountain Gold Mine,” Equinox Gold (website), https://www.equinoxgold.com/projects/castle-mountain/ – snapshot.

[45] Carlin-type gold refers to the sediment-hosted disseminated gold deposits in central Nevada’s Carlin Trend, characterized by invisible, microscopic gold in arsenic-rich pyrite and arsenopyrite. Chemical analysis determines if dissolved gold is present.

[46] Perdito Exploration Project Environmental Assessment (Environmental Assessment, DOI-BLM-CA-D050-2017-0037-EA), U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, October 2017.

[47] This figure was determined according to annual claim maintenance fees paid to the BLM in June 2018. Between the two men, they have a combined 608 active and 1,771 closed lode claims within the Mojave Desert as of 2019. The duo also has a group of claims in the Malpais Wilderness. Source: https://thediggings.com/owners/2278929 (Noel Cousins mining claims), https://thediggings.com/owners/1176787 (Steven Van Ert mining claims)

[48] News Staff, “Update on mining at Conglomerate Mesa (Press release for Friends of the Inyo and the Sierra Club),” Sierra Wave Media, October 31, 2018.

[49] As of September 1, 2019, the annual maintenance fee will be raised to $165.

[50] Tom Budlong, “Once Again Threatened by Gold Miners: Conglomerate Mesa, On the Western Rim of Owens Lake,” Desert Report, December 11, 2017.

[51] The Friends of the Inyo: Conglomerate Mesa Newsletter, Vol. I, June 12, 2019.

[52] Mark Waite, “Sterling Gold mine life may be extended,” Pahrump Valley Times, March 5, 2014.

[53] “Projects: Gold Road Mine Project,” Para Resources (website is no longer active).

[54] Many of these companies are foreign-based, but most of their investors are U.S.-based.